Health equity & junk food marketing: Talking about targeting kids of color

Friday, November 17, 2017To ensure that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible, we must remove obstacles to health.1 In the United States, junk food marketing to children is one of those obstacles because it encourages unhealthy diets and, ultimately, fuels disease. Such marketing is also a racial and health equity issue because junk food companies specifically target children and youth of color. Understanding and communicating effectively about this type of targeted marketing is a critical step toward achieving health equity.

Research shows that our preferences for food are established when we are very young,2 so advocates are increasingly recognizing and concerned about the harms of junk food marketing to kids. We wanted to know: When advocates communicate about junk food marketing, do they talk about health equity? To find out, we analyzed reports, websites and other materials from organizations around the country that are working on issues related to food marketing. We found some mention of the disproportionate amount of junk food marketing targeting children and youth of color, but we also identified many gaps in that discussion. In this framing brief, we describe what we learned, show why children of color should be at the forefront of our conversations about and actions to reduce target marketing, and suggest how we all can get better at discussing this critical public health and social justice issue.

Target marketing: What is it and why does it matter?

Communities of color have been the hardest hit by diabetes and other nutrition-related diseases. Food marketing is one serious obstacle to healthy eating patterns that can help prevent these disease risks. Food and beverage companies aggressively target communities of color with marketing for foods and drinks that are low in nutrition and high in sugars, salt and fats — the very foods and beverages that contribute to these diseases.3 Almost no marketing is for foods and beverages that families should eat more of, like fruits, vegetables or whole grains.

With the rise of digital technology, targeted marketing for sugary sodas, energy drinks, salty snacks, candy and fast food has become especially pervasive. Food and beverage companies align their marketing practices with the ways that consumers use social media, cell phones, gaming platforms and other digital devices to target consumers wherever they are at all hours of the day, particularly on their mobile devices, where marketers concentrate their spending.4 For example, digital marketers can follow Snapchat users through the app's McDonald's filters on their smartphones or use GPS coordinates to locate them as they approach a fast-food restaurant.

Using digital tools, marketers collect an unending stream of data about purchases, location, preferences, behaviors and more. Those data can exacerbate inequalities because they are shaped by current and past discriminatory policies and practices. For example, Jim Crow laws such as redlining have kept people of color out of certain neighborhoods5, 6 and limited their access to affordable, fresh and healthy food. That impacts purchasing patterns, since where people live — and the products made available to them there — influences what food people prefer and buy.

Once a community has shown a preference for a product, the food and beverage industry then uses purchasing data to inform additional spending to continue marketing that product, regardless of whether it is healthy. This pattern reinforces inequities and keeps communities of color on the receiving end of junk food marketing, which cements adverse health outcomes in the future.

A digital bull's-eye on kids of color

Data mining is even more problematic when it is used to target children, who are especially vulnerable to advertising. A child's online viewing and activity data can be used instantly to determine what content they'll be shown — and what junk food ads they'll be served — in the future. Since kids of color are at the vanguard of using digital media, their exposure to digital marketing is even higher. Youth of color get what researchers call a "double dose" of unhealthy food and sugary beverage marketing because they are exposed to mainstream campaigns aimed at all children and youth as well as campaigns targeted to their own communities. In practice, that means that, for example, Black children and teens end up seeing more than twice as many ads for energy drinks and regular soda compared with white children and teens, and 60 percent more fast-food ads.3

Marketers also target communities of color — and youth in particular — because they see them as cultural leaders. According to the University of Georgia's Selig Center for Economic Growth, young people of color "are trendsetters and tastemakers for young consumers of all races."7 Similarly, drawing on Nielsen data, Advertising Age describes young African-Americans as a group that "shapes consumerism and, in many instances, mainstream culture, like no other."8 Consequently, says McDonald's U.S Chief Marketing Officer, they "set the tone for how [companies] enter the marketplace."9

What's more, the digital landscape is evolving rapidly. Innovations that marketers use to target certain demographics more precisely often go under the radar, especially in their early phases. Even when companies are transparent about new and emerging tactics, such as when advertising executives showcase their campaigns at industry awards festivals, the health consequences of their practices remain hidden, leaving the public with the false impression that such campaigns are benign. This makes it all the more important for advocates to stay abreast of ever-changing marketing technologies and to communicate their health impacts to the field.

Are children of color included when we talk about junk food marketing?

How advocates frame the issue of target marketing will determine whether the public, policymakers, and even marketers themselves, see the problem.

Framing is how our minds recognize patterns of ideas, categorize them and derive meaning from them. It is the translation process between incoming information — things we see, read or hear — and the ideas already in our heads. Frames influence how people react to ideas, so how an issue is framed can affect whether it has popular or political support; the frame influences what solutions seem viable.

In the case of junk food marketing, it means we have to talk about race and ethnicity. Targeted junk food marketing is a racial and ethnic issue because of its roots in historically discriminatory policies and practices. Those roots manifest in today's inequities, such as the fact that African-American and Latino children are disproportionately exposed to more marketing than are their white counterparts,10-12 and food and beverage industry representatives themselves make clear that children of color are a key group of focus. One Coca-Cola executive pointed out that "86 percent of [the company's] growth through 2020 for Coca-Cola's youth-target market [would] come from multicultural consumers, especially Hispanic," and concluded "focusing on this segment [is] critical to the company's future growth."13

In other words, since the food and beverage industry explicitly focuses on kids of color, advocates must too. Additionally, advocates need to talk about the connection between their work and racial and ethnic equity; otherwise, the solutions people propose won't address equity either.

To find out whether children and youth of color are in the frame when advocates talk about junk food marketing, we reviewed how leading public health advocacy and research organizations describe food and beverage marketing in their research reports, on their websites and in other materials.

We found that although ethnically targeted marketing of junk food to children is clearly documented in published research, and many documents address marketing to children in general, few explicitly focus on targeted marketing or include images of children or families of color. Many documents mention health disparities, but most fail to explicitly connect the problem to junk food marketing — or why it is a health equity issue.

A complicated relationship

Although junk food marketing targeted at communities of color is a growing health issue that we must address, doing so is complicated for many reasons. To start, many food and beverage companies have longstanding connections in communities of color and are well regarded. The companies often bring jobs and dollars to under-resourced communities. Many are racially and ethnically diverse, with hiring practices centered around equity. And their corporate social responsibility campaigns and philanthropy frequently support organizations of color.

While food and beverage companies donate to a variety of children's advocacy organizations, the funds they provide to groups of color are significant because those organizations often do not enjoy the same level of philanthropy as others and may depend more on corporate donations for their survival. Further complicating matters, these companies have long promoted positive images of people of color in their marketing — something sorely lacking in other media.

Despite these relationships and financial contributions, junk food marketing targeting kids of color has negative health consequences. Though companies may not intend for their marketing to harm communities of color, it encourages children and teens to consume food and beverages that threaten their health and longevity, contributing to diabetes, heart disease and a range of other conditions as they age. And with new research and news coverage about the relationship between food and disease growing at a steady clip, it is unlikely that food and beverage companies are unaware of their products' potential to do harm.

Community leaders have described how targeted marketing can mislead members of their community, making it harder to promote health. The Rev. William H. Lamar IV, pastor of the historic Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C., told the Washington Post that he was grateful that companies such as Coca-Cola had supported these organizations but that their philanthropy did not "negate the science or the fact that their marketing is mendacious." And the Rev. Delman Coates, senior pastor of Mt. Ennon Baptist Church in Clinton, Maryland, emphasized how industry's exploitation of people of color has evolved but not ended: "As a person of African-American descent in this country and with a knowledge of the history, I'm deeply saddened by the way African-American slaves were used for the production of sugar and now African-Americans are dying because of sugar."

We are motivated by our core value of health equity for all. Even when companies bring financial resources to support the good work being done by organizations serving communities of color, that does not give them carte blanche to market products that harm health. If food and beverage companies are as committed to serving communities of color as they say they are, then they should align their practices with their promises by marketing only healthy products to children and youth.

How can we put children of color in the frame when we talk about junk food marketing?

Fighting targeted marketing is challenging, both because of food and beverage companies' reach — they have occupied rural and urban places (Figures 1-2) and digital spaces alike — and because of their deep pockets. Even when advocates try to counter targeted marketing, they usually can't compete with the frequency of the food marketing or the appeal of industry's message.

Still, progress is possible. To be sure children and youth of color are visible in the frame whenever we talk about junk food marketing, we can illustrate the marketing landscape around kids of color and embed those descriptions in good strategic communication practices, which include expressing our shared values and naming clear solutions.

Illustrate the target marketing landscape

How can we trigger the idea that junk food marketing to kids of color is a pervasive health equity problem that demands solutions? Begin by describing how communities of color have to contend with an environment that has more junk food marketing than others. You could point out that outdoor advertising for high-calorie food is highest in Black and Latino neighborhoods,14 that African-American youth are exposed to more TV ads for junk food,15 that healthier food costs more on Indian reservations while junk food costs less,16, 17 or that Black communities are disproportionately exposed to child-directed marketing displays at fast-food restaurants.18 Often there is more to say about the environment than time to say it — especially when you are talking to reporters — so describe those parts of the environment that link logically to the specific changes or policies you seek. (For more facts on target marketing, see http://www.foodmarketing.org/resources/racial-and-ethnic-target-marketing/.)

Connect to shared values

Next, say why you care about junk food marketing that targets kids of color. Values matter because they help people connect to messages and become motivated to act. Just reciting facts and figures will not shift people's thinking, especially if those facts are out of sync with their underlying beliefs about the way they think the world should work.

Values that give meaning to advocacy work, such as fairness and society's collective responsibility to children, appeared regularly in the food marketing narratives we analyzed, including in data-driven reports and documents. However, these and other values were rarely linked to marketing that targets children of color. We can do better.

Fairness is one widely shared value that is at the core of health equity. Ideas about fairness can manifest in many ways. People might recognize unfairness when they learn that data targeting is, by its very nature, rooted in patterns of historical inequity and discrimination. Many people will relate with the idea that it is unfair for parents to be held responsible for marketing they can't control. Others will connect with the injustice inherent in aggressive marketing practices that disproportionately target some communities with harmful products that can worsen health.

Whatever value you choose, whether fairness, health or something else, be sure to express it early in your message.

Present specific solutions

Finally, develop a clear, simple description of the desired policy or systems change that will solve the problem (or at least get us closer to solving it).

Advocates and researchers from a range of disciplines are pursuing different approaches to address food marketing to children. Many strategies, like expanding industry self-regulation, strengthening nutrition standards, and limiting brand advertising, would benefit all children, including kids of color.

However, as marketers increasingly move into the digital space,4, 19 so, too, must efforts to protect children from harmful food and beverage marketing. Addressing pervasive digital marketing is complex, but it can be done: Advocates in the United Kingdom illustrated one possible approach when the Committee of Advertising Practice banned marketing to children younger than 16 years old in non-broadcast media (including online and social media).20

Whatever the approach, it is worthwhile to explore solutions that focus on digital marketing. Since we know that marketers use data-driven tactics to target children and youth of color, we need solutions that also focus on digital targeting, such as changing the mix of products marketed on YouTube channels popular with children of color. (For examples of policies and practices to address target marketing, see digitalads.org.)

Any debate about a solution will be rooted in fundamental questions about responsibility, namely: Who is responsible for taking the actions to solve this problem? When we name our solutions, we must also say who is responsible for putting them in place. There is an overwhelming tendency in the U.S. to default to personal responsibility for almost every problem; most people will find it easier to talk about what individuals can do than what companies or government institutions should do. Thus, explicitly naming who should take action is paramount.

In our review of materials, we found that advocates and researchers fighting junk food marketing are, in general, conscientious about expanding the frame to highlight how the food and beverage industry can take responsibility for the ways it targets children. Far less often, however, do they explicitly address how the industry, along with other community and government stakeholders, can protect children who are disproportionately targeted with junk food marketing.

Put it all together

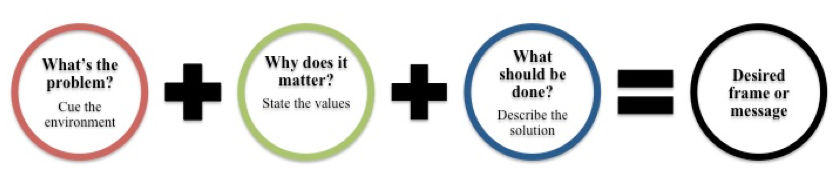

An effective frame around junk food marketing to children of color will illustrate the environment, connect to values and point to solutions. The message will answer three questions:

- What's the problem?

- Why does it matter?

- What should be done?

The order of the statement can change, but it's important to describe the environment early. Doing so will help audiences understand why a solution that focuses on changing policy or corporate practices matters when it comes to health. This is especially important for audiences who are not from the community exposed to the marketing; if they are not being targeted, they won't see it. Your description needs to make it visible.

In the sample message below, we show how a researcher or advocate could use this formula to describe marketing to children of color and what to do about it. We begin with a general statement to cue the environment, describe the problem and establish our values. Then, we get specific about the solution, in this case asking food, beverage and technology companies to restrict digital marketing to protect children and youth of color.

Sample message

We all want our children to be healthy and thrive. Junk food marketing is a big obstacle to health because research shows it affects children's diets, both now and later in life. What's worse is that junk food marketers target children of color disproportionately with ads for salty, sugary snacks and use kids' smartphones and social media accounts to reach them directly — often without parents' knowledge. Food and beverage companies target Black and Latino children because the companies consider them cultural leaders — other kids follow what they do. Maybe that would be OK if the foods were healthy. But they're not. When junk food marketers with big advertising budgets compromise kids' health this way, it's simply not fair to them, their parents or their communities. Internet and technology companies need to have clear, industry-wide policies and practices for how food and beverage marketers can engage with kids and teens without putting their health at risk. With strong, consistent guidelines in place, we can make sure all children in the United States are able to grow up in an environment that supports their health.

Adapt your message based on your specific target (the audience), the solution you seek, and who is delivering it (the messenger). (See the "Interview gone wrong" and "Interview gone right" sections at the end of this brief for an example of how to stay on message.)

Conclusion

Whenever we are communicating about food marketing, we should ask ourselves: Are we being explicit about marketing that targets children of color and why it matters? Are we addressing racial and ethnic targeting? Do we make it easier for people to see why structural and systemic changes to improve the marketing environment in communities of color are necessary?

When the answers to those questions are "yes," and when advocates are able to state solutions clearly and evoke values that resonate, they will be making the case that marketing that targets kids of color is a health equity issue and a threat to community health; that it is a problem that demands action; and that we all deserve to live, work, learn, play and raise our children in environments that are conducive to good health.

Interview gone wrong

Once we have figured out what has to be done, who has to do it, and how to frame the issue, we have to be able to talk about it, in public and on the record. Because policymakers track issues via the news, the way the media portray topics like target marketing may influence policy decisions on the issue. Though journalists choose the interview questions and, ultimately, what makes it online, on the air or into print, advocates have a lot of control over how the interview unfolds. Whenever we talk with reporters, we have the opportunity to educate them about problems and what to do about them.

But talking with reporters can be intimidating. Staying on message and keeping children of color at the forefront of marketing discussions requires preparation and practice. Without it, even the most seasoned speaker can get off track and forget that once the goal is to focus on target marketing and disparities, those should be the principal themes of the interview. Let's see what happens when an advocate talking about new food marketing policy efforts gets in front of the camera.

Reporter: I don't let my kids watch TV, so do I need to worry about food marketing?

Answer: Well, TV is definitely an important tool for advertisers, but promotions like TV advertisements are just one way marketers reach kids. These days, most kids watch several screens at once, so companies can surround our kids with marketing.

Reporter: When you say companies "surround them," what does that mean?

Answer: Marketing happens with products designed just for kids like Kraft "Lunchables," in places kids congregate like schools, at prices they can afford, all personalized with digital marketing. That means kids are exposed to marketing in schools, stores, online on their phones and tablets, and in many other ways.

So far so good. Let's keep going.

Reporter: Is this really something that parents should be worried about? It seems like there are a lot bigger things to worry about than marketing. Isn't advertising just a part of modern life that isn't going to go away?

Answer: Marketing may be part of U.S. culture, but the food and drink ads inundating our children are for exactly the wrong products. Food and beverage companies overwhelm kids with ads for their least healthy items, like sugary sodas, high-calorie fast food and salty snacks.

Reporter: Well, but kids see advertising for healthy food, too, correct?

Answer: Not very often. Most studies show that advertising for healthy items is rare and just can't compete with junk food marketing. For instance, one researcher found that in one year, a single company spent more than $30 million marketing just one sugar-coated cereal. That same year, the U.S. government spent just $50,000 per state on nutrition education for school children.

Now you are off track. These are great points, but not if your priority is keeping kids of color — and policies to protect them from target marketing — in focus. Instead, the discussion is now about food marketing to kids in general — not a bad topic, but not where you wanted to end up. Let's try the interview again.

Interview goes right

Reporter: Is this really something that parents should be worried about? It seems like there are a lot bigger things to worry about than marketing. Isn't advertising just a part of modern life that isn't going to go away?

Answer: This is indeed something parents should be worried about. In fact, all Americans should. Here's why: First, the foods that are marketed to kids are overwhelmingly not good for them — high in fat, sugar and salt, low in nutrients. Even worse, marketers are aggressively targeting some communities, especially African-Americans and Latinos, where there are very high rates of diabetes. That's a problem for everyone in a country that values fairness.

Reporter: How do they target Black and Latino kids? I remember the Beyoncé Pepsi ads…

Answer: Well, that's certainly a good example. Marketers use every technique they have to target children and youth of color, especially by personalizing ads with digital marketing. African-American and Latino kids are heavy users of technology, so marketers use digital strategies to reach them. That's in addition to all the advertising on specific ethnic media that kids are exposed to, like advertising on Black- or Latino-targeted TV shows and websites, as well as the advertising they're exposed to on mainstream channels and websites. It adds up! Researchers call it a "double dose" of junk food marketing.

Reporter: Wow, that's a lot of marketing. Why target those groups specifically?

Answer: Basically, marketers' goal is always to sell more of their products and promote long-term allegiance to their brand. They say that Black and Latino kids are "trendsetters" or "tastemakers" who'll influence their friends and peers, and, according to some marketers, ultimately "make or break" a brand. But that's exactly what worries us when we're talking about junk food and sugary drinks, since Black and Latino communities experience higher rates of serious nutrition-related health issues like diabetes and heart disease. Our nation can't be healthy until everyone is healthy. That's why we want food and beverage marketers to commit to policies that would protect Black and Latino kids from junk food marketing across every platform.

Now you're on the right track. Kids and communities of color are front and center in the conversation. The reporter may follow up with questions about what those policies might look like, what you hope the outcome will be, or next steps. Or the reporter may ask another distracting question. But by staying on track, you will have the discussion you want to have, focused on marketing that targets kids and communities of color and what to do about it.

This framing brief was supported in part by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Thanks to Jeff Chester, Matt Kagan, Katharina Kopp, Shiriki Kumanyika and Steven Lopez for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts.

© 2017, Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute

References

1. Braveman P., Arkin E., Orleans T., Proctor D., Plough A. (2017). What is health equity? And what difference does a definition make? Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

2. McGinnis J.M., Gootman J.A., Kraak V.I. (2006). Food marketing to children and youth: Threat or opportunity? Washington, D.C: Institute of Medicine Committee on Food Marketing and the Diets of Children and Youth.

3. Harris J.L., Catherine S., Gross R. (2015, August). Food advertising targeted to Hispanic and Black youth: Contributing to health disparities. UConn Rudd Center for Policy and Obesity. Available at: http://www.uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/272-7 %20Rudd_Targeted Marketing Report_Release_081115[1].pdf. Accessed August 30, 2017.

4. Ha A. (2017, April 26). Mobile now accounts for the majority of digital spending, according to IAB. TechCrunch. Available at: https://techcrunch.com/2017/04/26/internet-adverising-revenue-report-2016/. Accessed August 31, 2017.

5. Mock B. (2015, October 8). Remember redlining? It's alive and evolving. The Atlantic. Available at: http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/10/remember-redlining-its-alive-and-evolving/433065/. Accessed August 30, 2017.

6. Trifun N. (2009). Residential segregation after the fair housing act. Human Rights Magazine; 36(4).

7. Boschma J. (2016, February 2). Black consumers have 'unprecedented impact' in 2015. The Atlantic. Available at: http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/02/black-consumers-have-unprecedented-impact-in-2015/433725/. Accessed August 30, 2017.

8. Walker K. (2016, November 9). Reaching next-gen African American consumers. Advertising Age. Available at: http://adage.com/article/agency-viewpoint/reaching-gen-african-american-consumers/306661/. Accessed August 30, 2017.

9. Helm B. (2010, July 8 ). Ethnic marketing: McDonald's is lovin' it. Bloomberg. Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2010-07-08/ethnic-marketing-mcdonalds-is-lovin-it. Accessed July 27, 2017.

10. Kumanyika S., Grier S., Lancaster K., Lassiter V. (2011). Impact of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption on Black Americans' health. African American Collaborative Obesity Research Network (AACORN).

11. Grier S.A., Kumanyika S. (2010). Targeted marketing and public health. Annual Review of Public Health; 31: 349-69.

12. Grier S.A., Kumanyika S.K. (2008). The context for choice: health implications of targeted food and beverage marketing to African Americans. American Journal of Public Health; 98(9): 1616-29.

13. Cartagena C. (2011, July 5 ). Hispanic market the hot topic at Nielsen conference. Advertising Age. Available at: http://adage.com/article/the-big-tent/hispanic-market-hot-topic-nielsen-conference/228543/. Accessed April 12, 2017.

14. Cassady D.L., Liaw K., Miller L.M.S. (2015). Disparities in obesity-related outdoor advertising by neighborhood income and race. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine; 92(5): 835-842.

15. Powell L.M., Wada R., Kumanyika S.K. (2014). Racial/ethnic and income disparities in child and adolescent exposure to food and beverage television ads across the U.S. media markets. Health & Place; 29: 124-131.

16. Lee T. (2016, July 12). 7 foods that cost more on the Rez, and one junk food that costs less. Indian Country Today. Available at: https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/culture/health-wellness/7-foods-that-cost-more-on-the-rez-and-one-junk-food-that-costs-less/. Accessed September 6, 2017.

17. First Nations Development Institute. (2016). Indian Country Food Price Index: Exploring variation in pricing across native communities — a working paper. Longmont, CO. First Nations Development Institute. Available at: http://www.firstnations.org/system/files/Indian_Country_Food_Price_Index_6-30-2016_FINAL%20FIXED.pdf. (Registration required.) Accessed September 6, 2017.

18. Ohri-Vachaspati P., Isgor Z., Rimkus L., Powell L., Barker D., Chaloupka F. (2014). Child-directed marketing inside and on the exterior of fast food restaurants. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 48(1): 22-30.

19. eMarketer. (2016, September 13). US digital ad spending to surpass TV this year. Available at: http://www.emarketer.com/Article/US-Digital-Ad-Spending-Surpass-TV-this-Year/1014469. Accessed August 31, 2017.

20. Advertising Standards Authority. (2016, December 8). New rules ban the advertising of high fat, salt and sugar food and drink products in children's media. Available at: http://www.asa.org.uk/news/new-rules-ban-the-advertising-of-high-fat-salt-and-sugar-food-and-drink-products-in-childrens-media.html. Accessed August 30, 2017.