Issue 11: Silent revolution: How U.S. newspapers portray child care

Tuesday, January 01, 2002Imagine a news story so big, it touches the hearts and strains the pocketbooks of 10 million American families. It’s also a business story about a giant emerging industry that is beginning to rival agricultural crops in size and impact. It’s a story about women’s ability to pursue careers. It’s a science story, about advances in understanding how and when children’s brains develop capacity not just for knowledge, but also for citizenship. And it’s a political story about who and how many will enjoy the American dream.

You’ll have to imagine much of this story. American newspapers great and small have paid scant attention to a sea change in how Americans care for their young children. In 1950, a minority of women worked — about one in three. Now it’s a majority — six in 10.1 In 1950 most children under the age of five were cared for at home, usually by their mothers. Today only 14% of U.S. children spend their first three years in the full-time care of a parent.2 Even the majority of mothers with children less than a year old are working or seeking work.3

Increasing gender parity in education and career opportunity, the increase in single-parent families, the growth of the workforce over the past decade, and new limits on welfare benefits have invited — or pushed — women into the workforce in unprecedented numbers. As a result, child care has become a major industry, generating billions in revenues and creating thousands of jobs.

Not since the establishment of universal public education in the 19th century drew children from farms and factories into schoolhouses has there been such a turnaround in the lives of young people. At the same time, cognitive scientists have discovered that children can and do learn a great deal in their first five years and early relationships can shape what kind of people they will grow up to be.4 What’s absorbed — if the child’s environment provides them — are not just the shapes and sounds of letters, or how to hold a pencil and throw a ball, but reasoning, empathy for others and moral accountability.5

Research is unanimous that the quality of child care matters a great deal. It matters particularly for children coming from families with few resources — those unable to provide their children a richly stimulating and supportive environment at home. The most comprehensive study of child care associates high quality child care with improved school readiness and better thinking and language skills.6

Despite its importance to our society — laying the foundation for an educated and responsible citizenry — and to our economy — generating jobs and freeing parents to pursue employment — quality child care is scarce in the U.S.7 In some European nations, early childhood education is government-supported and universally available.8 But here, many parents strain to pay, often spending more for child care than for housing.9 As a result high quality care is much more accessible to the rich than poor or even middle class.10 Child care divides rather than unites us.

The severe shortage of quality child care and paucity of reporting may be related. News coverage can powerfully influence which issues the public and government officials pay attention to, and which are ignored. It also provides most of the information for interpreting those issues.

So we examined how care for pre-school children (those under 6 years old) has been reported in a national sample of newspapers. We chose newspapers over broadcast media because the press covers a wider array of issues and drills deeper. We examined the entire child care universe, from private homes to child care centers and pre-schools. We included all types of care providers — parents, relatives, nannies, licensed operators and others. We asked four central questions:

- How frequent is coverage, both on business pages and elsewhere in the paper?

- Which of the many issues surrounding child care are most often covered — the availability of placements, their affordability, their quality, the size and impact of the child care industry, etc.?

- How is child care framed? That is, which arguments or descriptions of reality get the most play, and thus have the greatest chance to influence public and official opinion? Which get the least, or are missing? For instance, how frequently do stories portray child care as inferior or superior to having a parent stay at home with children? Or describe it as a benefit business must provide to recruit top talent, particularly among women? Or as an educational intervention that might level the playing field between “haves” and “have-nots” and thus benefit society as a whole? Or as a prerequisite of successful school reform? Or as an intrusive expansion of public education, taking over tasks better left to families?

- Whom does the press most often quote on these issues — care providers, advocates, business people, politicians, parents, tax-payer groups, others? Since sources often are enmeshed in their own self-interest, who speaks influences how reporters portray issues.

Method

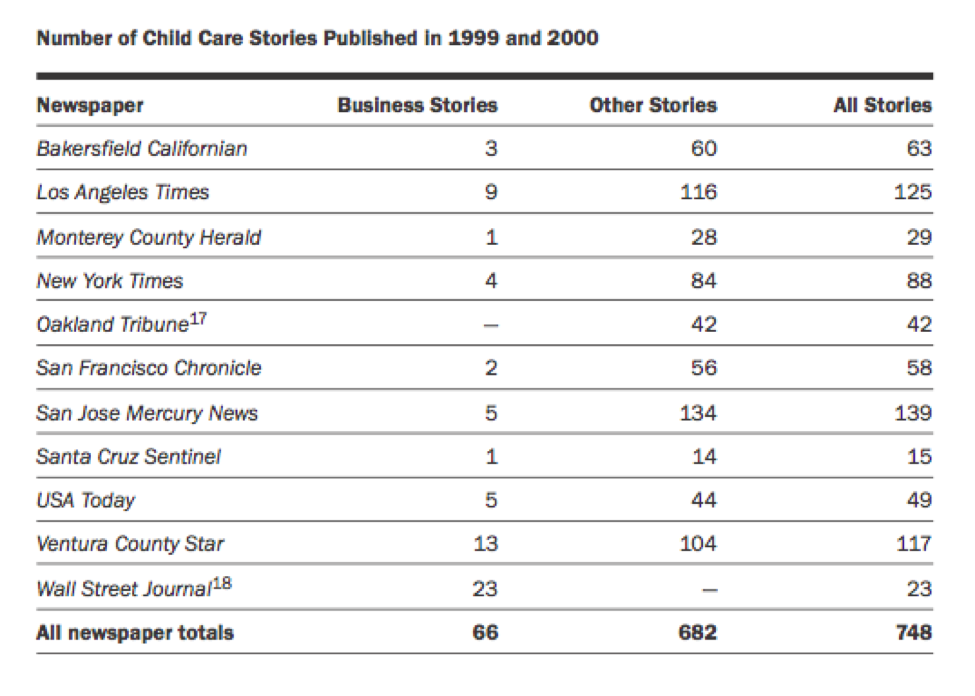

Using the Nexis database or the newspaper’s own archives, we looked at every story about child care published in 1999 and 2000 in 11 newspapers.11 We chose the nation’s four largest papers: The New York Times, USA Today, the Wall Street Journal, and the Los Angeles Times. And we selected seven regional papers, all in California communities that have begun to systematically examine the contribution child care makes to their local economies: the San Francisco Chronicle, San Jose Mercury News, Oakland Tribune, Bakersfield Californian, Ventura County Star, Santa Cruz Sentinel and the Monterey County Herald.

We chose stories in which a third or more of the content concerned child care, whether staff-written or from wire services. That eliminated hundreds of stories in which the only reference to child care was its availability at a meeting or church service. We screened out extremely brief articles (those with fewer than 150 words) because such truncated reports are often merely announcements. We also skipped letters to the editor because these generally comprise reactions to news, rather than the news itself. Finally, we excluded stories that did not appear in the home edition or the edition circulated in the communities undertaking the economic impact study.12

Of the remaining stories, we analyzed every one from business sections (including the entire Wall Street Journal) and every second article in other parts of the newspaper. Our approach was bifocal, necessitating two categories. We wanted to measure how much attention business pages gave this major, expanding industry. And we wanted to see how the issue fared more generally in non-business sections.

By including every story on the business pages, we avoid any margin of error. In fact, the numbers of stories in both business and general news sections are based on actual counts. The content analysis of non-business stories, however, is based on a random 50% sample allowing us to generalize with considerable precision.13

Findings

1. How often is child care the topic of stories in the business section? Elsewhere in the paper?

Child care is all but invisible on the business pages of our sample newspapers. On average, California newspapers averaged just two stories per year about child care in their business sections. Yet child care is a $5.4 billion-a-year industry in the state, as big as vegetable crops, and that’s only counting licensed care.14 The industry’s minimal profile extends beyond California. The New York Times ran just two stories per year about child care on its business pages. This is surprising. Child care ought to be newsworthy for a variety of reasons: It is provided in every community across the nation. Three of every four children under the age of six spend considerable amounts of time in the care of someone other than a parent.15 Formal child care is also among the most rapidly growing businesses in the U.S. And it’s a troubled industry, experiencing considerable difficulty finding and keeping staff. Finally, the field is entrusted with something priceless, our children.

Elsewhere in the newspaper, child care stories appear with greater frequency. But compared with other issues that affect huge numbers of citizens, they have an infinitesimal presence. Among the scores of thousands of stories published in the general news sections of the Los Angeles Times in 1999 and 2000, only 116 concerned child care. On the non-business pages of the New York Times, only 84 stories concerned child care.

To put these numbers in perspective, consider that in an earlier study of three large California newspapers16 we found that about 5.5% of the stories on news section fronts (or promoted there) and editorial and op-ed pages were focused on education. Stories about child care (or nursery school or day care), by contrast, represented a fraction of 1% of the stories in our sample newspapers.

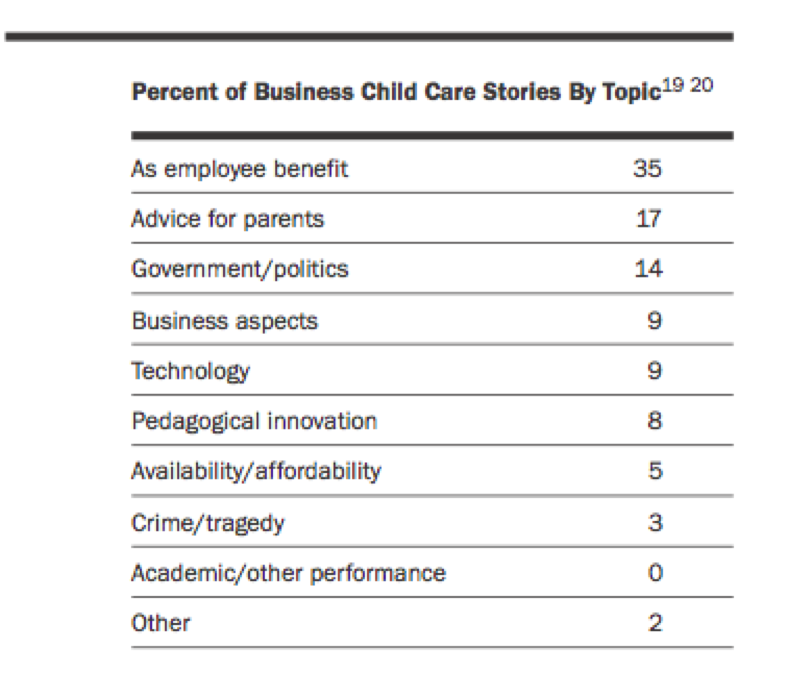

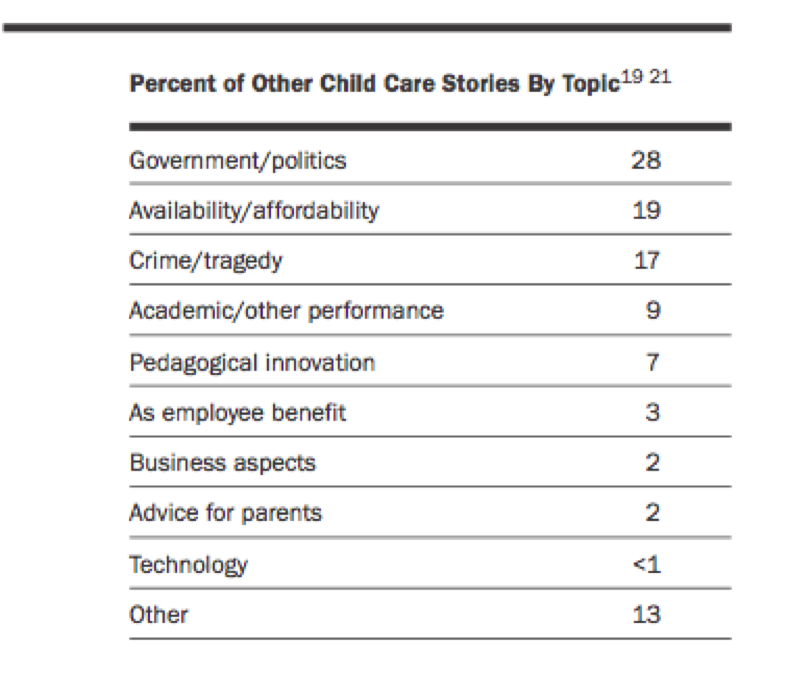

2. Which aspects of child care get the most attention on business pages? Elsewhere in the paper?

When child care does crack the business pages, more than a third of the time the topic concerned how it expands the talent available in a growing economy by permitting both parents to advance their education or work. Surprisingly, the second most popular category was advice for parents — often about choosing the right child care provider, or claiming child care tax credits. Equally surprising, the imbalance between supply and demand — which might be considered a business opportunity — rarely rated ink.

In the rest of the paper, the topic was most often politics or government actions (28% of stories). Advocates may draw hope that discussion was focused on an arena in which people have the power to back up words with actions. For instance, during the first nine months of 2000 child care was addressed by each of the major presidential candidates. Former Senator Bill Bradley made it a major element of his campaign. In fact, stories about the candidates’ promises comprise one out of every five government/politics articles. But they only temporarily inflated the salience of this cardinal category. The second most frequent topic concerned the affordability and availability of child care. And the third was the disturbing subject of crime and tragedy associated with child care.

Here’s how we defined the topics:

- Government or politicians’ actions or plans including criticism from any quarter. These included campaign promises concerning child care, debates among politicians, public or advocate criticism of current government practice, e.g., lack of funding, implementation, building, application procedure, reimbursement, etc. They also included licensing and regulation if the story was told from a government point of view — discussion or criticism of official plans or policies. If told from a business point of view — hoops and hurdles or requirements or steps, they were placed in “Business aspects.”

- Availability and affordability issues, including labor or compensation. These were generally about difficulty finding affordable or quality child care and other market conditions, strikes and labor complaints.

- Crime or tragedy in child care settings. These were articles about child abuse, neglect or accidents at such facilities. They also include outbreaks of illness.

- Performance of children in high vs. low quality child care, or institutional child care vs. parental care, etc. Generally these were reports about academic studies, but they could be less formal analyses.

- Pedagogical programs, innovations. These were descriptions of model, unusual, or new programs or child care facilities.

- Child care as an employee benefit; issues of work/life connection. Stories about the advantages to a company of providing child care at the workplace or subsidies for child care, or about how employees juggled work and child care were placed here.

- Advice for parents/news you can use. These articles often took the form of Q and A with one or more experts giving advice, such as how to choose a good preschool or claim a tax credit for child care.

- Business aspects of child care as an industry. Stories describing its size, importance, and other characteristics — expenses, licensing requirements and processes, contribution to overall economy, growth — went here. It also included descriptions of sectors in the field such as home care, center-based care, nannies, etc.

- Technology. These articles described how advances in computer, internet or other technology improved learning, surveillance or other aspects of child care programs.

3. How is child care framed on business pages? Elsewhere in the paper?

Journalism reduces the great buzzing confusion of life to the simplified narrative of news. It does so by including certain perceptions about a particular event or issue and discarding others. A frame analysis looks for key themes expressed as arguments, metaphors and descriptions to reveal which parts of the issue are emphasized, which are pushed to the margins and which are missing.

The process begins with a diverse list of perspectives drawn from news and research literature. We examined 50 specific child care frames expressing these perspectives. The frames were divided into six categories: safety/security, economic, educational, social, health, and regulatory/political. Each frame could be expressed either in a positive direction, e.g., “children are safe at child care facilities” or negatively, “children are not safe….”

Most frames were explicit, stated by a source or reporter in words approximately the same as the sentences expressing our frames. In order to minimize subjectivity, we refrained from interpretation of latent messages. However, if a story described children being harmed or threatened in a child care center, we coded an implicit message that child care is not safe. Our interpretive rule was: Code an implicit frame only when it would be obvious to an intelligent reader with at least a high school education. When stories contained both a positive and negative version of the same frame, we chose the version mentioned more often and higher in the story as the predominant frame. Below we describe the frames appearing in the most and fewest child care stories.

Frames appearing in business stories

Child care provides broad economic benefit — to parents by allowing them to work or study; to business by expanding the talent available to employers; and to society by enlarging the tax base and raising community wealth. This was by far the most common theme in business coverage, appearing more than three times as often as the next most frequent frame. An example: William C. Ford Jr., chairman of Ford Motor Company, told the New York Times: “Enlightened corporations are beginning to understand that social issues are business issues. Ultimately, businesses can only be as successful as the communities and the world that they exist in.”

Other business frames described the demand for quality child care outstripping supply; the notion that government ought to help ensure such care; and the idea that some parents will need help paying for child care.

Some anticipated frames in business sections barely appeared or were absent. One example is the argument that business can’t afford to subsidize child care for employees. Instead we found counter-arguments: “The payoff [of companies providing child care benefits] is low turnover, happy, motivated, loyal and productive employees — and knowing that you are doing the right thing,” said Sheri Benjamin, CEO of the Benjamin Group, in the San Jose Mercury News. A second absent frame was the idea that government cannot provide child care efficiently or effectively. Another no-show was the frame that government regulation of the child care business should be reduced or eliminated.

Frames appearing elsewhere in the newspaper

Elsewhere in the newspaper, a broader and more complex portrait of childcare was drawn. But its general features were similar. In descending order of frequency the most common frames were:

The demand for quality child care is growing much more rapidly than the supply, largely due to a lack of money to pay teachers and aides. A key statistic: “Statewide, California has about 800,000 licensed child-care slots for 3.9 million children needing care,” California Child Care Resource and Referral Network, quoted in the San Jose Mercury News. A sound bite: “Parents can’t afford to pay and workers can’t afford to stay,” Patty Siegel, executive director of the California Child Care Resource and Referral Network, in the Ventura County Star.

Government ought to play a role in making quality child care available to every parent who wants it. Examples: “Universal preschool is our nation’s next step to ensuring high quality educational access,” Delaine Eastin, state superintendent of public instruction, in the Los Angeles Times. Or, “in the Greece of antiquity, it was up to the citizens to build a new library, a new university. The public had to be caregivers. The mark of a great society is what you build for the children,” then-Los Angeles Assemblyman Antonio Villaraigosa, in the Los Angeles Times.

Child care benefits everyone: It permits parents to work and thus improve their standard of living; expands the talent pool available to business holding down labor costs; and reduces stress and guilt in working parents. This “everybody wins” frame wasn’t limited to business stories. An example: “Child care is kind of an invisible link between the community and employers. It allows parents to work and it prepares children for school. Ultimately how we provide for young children’s development will support all of us — if we do it well — when they grow up,” Jeanie McLaughlin, child care specialist with the Santa Clara County Office of Education, in the San Jose Mercury News.

The safety of children in nursery schools and child care facilities is problematic. Violent or sexual incidents occurring at centers or by their staff members, or even former staffers, received prominent play. So did accidents. Both positive and negative frames were common. The positive prevailed, but by a slim margin. A sound bite constituting a positive frame: “Parents should be reassured that day-care centers…are really about the safest places in the world for little kids to be in terms of injuries,” David Chadwick, a child-abuse prevention specialist told the Los Angeles Times. A key statistic within a negative frame: “Two in three child-care facilities surveyed by a federal consumer safety agency had hazards that put children at risk,” wrote the Los Angeles Times quoting the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission.

Quality child care makes a positive difference for kids — improving IQ or at least readiness for kindergarten. An example comes from the report, Crucial Issues in California Education 2000: “Reading scores will not climb in the early grades as long as access to preschooling remains so unequal across and within counties in California,” quoted in the Ventura County Star. Or “Poor children in quality day care from infancy to age 5 outperform peers mentally and are more than twice as likely to attend college,” in USA Today.

Quality child care helps level the academic playing field for children of low-income parents. An example of a sound bite: “Let us realize that education is the greatest anti-poverty, the most powerful anti-discrimination strategy we could ever have,” then-Vice President Al Gore, quoted in the New York Times. Or, “If racial equality is America’s goal, [reducing the gap in availability of quality child care] would probably do more to promote this goal than any other strategy that could command broad political support,” Christopher Jencks, Harvard professor, in the Los Angeles Times.

Quality child care is expensive, beyond the means of many Americans. A sound bite: “An awful lot of people who work in middle-income jobs are struggling to make ends meet; They’re having to make some horrible choices like whether they’re going to buy health insurance, child care or food,” San Mateo County Supervisor Rich Gordon in the San Francisco Chronicle. A number of frames we thought might be prominent were, in fact, scarce in the non-business sections of the paper. Among them:

- Parents should shoulder some or all of the cost of child care for their offspring.

- Employers cannot afford to provide child care for their workers.

- Government cannot afford to provide child care.

- Government cannot provide child care efficiently or effectively.

- Child care reduces the quality of parenting or is something “bad parents” seek.

- Child care increases government interference or control over functions that ought to be restricted to the family.

- Child care reduces later delinquency, crime and associated costs.

- Child care exposes kids and their families to illness.

Several other frames were common, but we failed to achieve adequate agreement between coders to be sure we were not just being subjective in our interpretation.22These frames included:

- Employers should pay or share in the cost of child care for their employees.

- Child care should be oriented toward developmentally appropriate education and not merely custodial.

- Lack of quality child care hurts the poor more than other economic classes.

Despite very thin coverage, in both business sections and the rest of the newspaper, the framing pattern came closer to the viewpoint of advocates of universally available quality child care, than to its opponents, or even its skeptics. All but one of the most common frames we found portrayed child care as socially valuable. The exception — about the safety of child care centers — was mixed, with safe frames slightly outnumbering unsafe ones. Of the frames we expected to see, but which rarely surfaced in our sample, seven of the eight portrayed universal child care as undesirable or impractical.

Whom did reporters quote?

The story of childcare has been told primarily by parents, government officials, the providers themselves, other business people, advocates for child care, researchers/experts, and finally, politicians. Somewhat surprisingly, K-12 teachers were rarely quoted. And representatives of taxpayer groups were so sparse in our first cut of the data, we didn’t even create a category for them. Social workers and clergy were also infrequent voices. Health professionals, young people 12 and under, police, lawyers and judges were somewhat more frequent sources, but still scarce. The law enforcement and court officials were typically quoted in crime and tragedy stories located at child care facilities, rather than as advocates or opponents of early childhood education.

The most often quoted groups were more likely than not to be advocates of expanded child care availability. Parents were most often associated with pleas for more quality placements. Government officials, however, sat on both sides of the fence. Providers and advocates argued the pro side, seeking greater resources from government and employers. Almost all researchers reached conclusions favorable to expanded child care.

In news reports, politicians also lined up more on the pro than con side, although the strongest advocates were the least successful. Senator Bill Bradley proposed the most generous early childhood education plan, Vice President Al Gore the next most expansive and then-Governor George W. Bush the least. Although child care figured in the campaign promises of presidential aspirants, political quotes were scarce at the operational and local levels. Senators, congressional representatives, state legislators, county supervisors and city council members were rarely quoted on the topic. Representatives of the business community were also more pro than con, although reports tended to focus on companies which had adopted “family- friendly” policies.

Implications of the analysis

In 1999, we published an overview analysis of reporting about child care from 1994–1998 in 18 of the largest newspapers in the U.S.28We found child care portrayed as a serious policy issue, but “as a necessary evil, rather than as a social good.” On both business pages and elsewhere in the newspaper, this has changed. Coverage over the past two years emphasizes child care as a social benefit, particularly for poor children. The frame of child care as inferior to parents staying home with their children has faded. So has the frame of parents being solely responsible for financing child care. The most frequent frame in the earlier analysis advocated government responsibility at least for helping families afford child care. That frame continues to be strong on both business and general news pages.

The analysis of 1999 and 2000 coverage of child care would be very good news for advocates of universally accessible child care of high quality, but for one thing. The issue is virtually invisible on business pages and barely noticeable elsewhere in the paper. It appears to slip between traditional newspaper beats. Its abundant newsworthiness deserves better.

Recommendations for Advocates

The news coverage we examined indicates that the benefits of child care, for families and communities, can be reported effectively. The job advocates now face is increasing the volume. They can do this systematically by creating news, piggybacking on breaking news, submitting their opinions in the form of letters and visits to editorial boards, and — most important — cultivating relationships with reporters. Journalists are like other Americans—they learn what’s important from the news. If child care and early childhood development are absent from the business pages, advocates need to meet with business reporters, bring their data, evidence, and illustrations, and help those reporters explain to their readers why child care is a vital economic issue for the entire community.

Create news

When there’s recognizable news, it will get covered. In our sample there was an outstanding example that illustrates how advocates can increase coverage emphasizing the economic contributions of the local child care industry. Santa Cruz Sentinel business editor Jennifer Pittman gave extensive front page coverage to a report released by the Santa Cruz county Office of Education. Headlined, “The enterprise of child care goes beyond caring for children,” the article described how child care creates 2,469 jobs in the county and generates $35.5 million annually, “topping the gross receipts of the county’s four top vegetable crops combined.”29

The Sentinel was able to delve deep because the advocates first created news and then made it easy to report. They conducted research highlighting local trends, documenting that child care is one of the fastest growing jobs in the state. They shared the research findings with reporters early, gave them background and ample time to talk to sources. They released the report at the Santa Cruz Chamber of Commerce business fair, to emphasize benefits child care brings as an industry. They connected the Sentinel with local spokespeople and good visuals. The result was the only front page story about child care as an economic issue in two years of news coverage.

Piggyback on breaking news

Along with creating news, advocates can make better use of newsworthy events, what journalists call a “news peg.” An example is the publication of Working Mother magazine’s annual list of best 100 companies for working moms. That story was covered repeatedly in our sample. It will be a story again when Working Mother publishes next year’s list. Advocates can anticipate that event and prepare local elements of their own. What do parents say about the community’s major local employers? What are those companies doing to contribute to healthy environments for families raising children in the community where they do business? Tied to the Working Mother list, advocates could extend and localize a likely story about child care on the business pages. Working Mother magazine’s annual list is only one story local advocates can anticipate. Others will surface. When they do, advocates can make the link to child care as an economic issue. To prepare, they’ll need to cultivate spokespeople, including local politicians, and create news focused on local investment.30The resulting coverage will help clarify child care’s contribution to parents, children, business and society.

Recommendations for reporters

Reporters appear to be stuck in a limited range of story ideas for child care. Especially on the business pages, the story is companies using child care benefits to attract and retain top talent and increase productivity, or a new child care center opening. And, of course, there was a good supply of the usual news- you-can-use: how to do background checks on providers; how to apply the child dependent care tax credits.

Not the same old story

These typical stories could push deeper. The dilemmas surrounding child care — availability, affordability, quality — need in-depth, frequent examination. For example, what constitutes “quality” child care? In one piece in the sample, Wall Street Journal columnist Sue Shellenbarger wrote, “High quality is the closest thing to a magic bullet you find in nonmaternal child care, erasing nearly every risk and yielding benefits in cognitive, language, math and social skills and behavior.”31 But, there’s not enough high quality care. Why? What would it take? Does the business community think it’s a worthwhile investment? Why or why not?

Who has creative financing models? For example, no one expects students or their families to shoulder the entire burden of four years of college tuition without loans or grants from government. Why is preschool — perhaps the most important time for learning and brain development — pay-as-you-go? Are there new models for making child care more affordable?

Business can help with supply by building centers, but how can it help with affordability? How can businesses avoid the problem the Marriott corporation faced after it invested in a child care center that its employees couldn’t afford to use?32

The Sentinel story reported that during the next 20 years “the number of children 0–2 in Santa Cruz County is expected to increase by 51%; the number of preschoolers by 52%.” Reporters can ask, what are the projections in this community? What will it take to meet the demand? Who is — or should be — attending to it?

Who is thinking creatively about solving the availability, affordability, and quality dilemmas and would any of those solutions apply locally?

The new story: The business of child care

Reporters have yet to investigate the business of child care. Most formal child care enterprises are small businesses, some operated by managers with extensive expertise in early childhood development but little knowledge of business plans. Reporters can mine the stories in the operation of child care. What makes child care profitable? What does it take to run a child care center or home care? How do those profit margins compare to other local industries? What loans/programs are available federally and locally? How do local programs cope with meeting demands? Who goes into the child care business? How many family child care providers own their biggest business asset: their own home? What are local financial institutions doing for child care businesses?

New story: Child care as an industry

But there is an even bigger story to tell. Reporters can ask, What does child care mean to the community? What kind of community do the companies want to do business in? And, What are the links between early childhood development and healthy communities? Journalists can reinterpret the issue of child care in light of new data indicating its expanded importance as a sector of society. Data from California show that the licensed child care industry generates between $4.7 and $5.4 billion in revenues statewide — similar in size to both the livestock and vegetable crop industries. The National Economic Development and Law Center, in its Fall 2001 study, Child Care and Its Impact on California’s Economy, reported that “the [licensed] child care industry employs more than 123,000 people in California, more than twice as many as the lumber industry. By providing a stable source of care, the child care infrastructure enables working parents to earn at least $13 billion annually — a substantial and sustained contribution to the state’s economic growth and overall prosperity.”33 The child care industry’s specific contribution to the economy in other states has not been researched, but it’s there, waiting to be revealed.

Reporters can ask: What contribution does child care make to the local economy? What is needed to cope with new demands? And, What is business doing to respond?

Childcare as a social issue

Because child care affects so many people so deeply — because of the preciousness of their children and the cost of the service — it has enormous news value. People are hungry for information about best practices, about which centers have the most equipped facilities and qualified staffs, about whether their philosophies are more custodial or educational.

Prominent educators have argued that public education reforms, such as smaller class sizes, will not succeed for poor children as long as many of them come to school less prepared than those from more advantaged homes. Should state education money be shared with child care centers if this is so? Should it be allocated mostly to centers serving poor families? Distributed to those families directly? What might that mean in terms of tax burden? In terms of the supply of qualified teachers? There are also interesting questions of what mix of education and free play is appropriate at which ages.

Perhaps because child care falls between established news beats, coverage has been scant. A wide variety of engaging stories wait to be told. Traditionally reporters have covered child care to highlight information parents need to make immediate decisions about their children’s care. But there’s an equally important role for news coverage. It must also carry information citizens and policy makers need to decide how much to invest in child care and early childhood development. Without that, our society won’t have enough information to make the important decisions about entire generations of children, who, as Mr. Rodgers says, “will become adults.” This study provided ample evidence that it can be done — it just needs to be done much more often.

Issue 11 was written by John McManus, PhD, and Lori Dorfman, DrPH, with research assistance from Karen White. Support for this Issue was provided by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and The California Endowment.

Issue is edited by Lori Dorfman.

© 2002 Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute

References

1 Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. “Changes in women’s labor force participation in the 20th Century,” Monthly Labor Review, 2/16/2000.

2 National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, cited in Los Angeles Times, 6/27/99, page A3.

3 Bureau of Labor Statistics, cited in Peth-Pierce, Robin. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care, 1998. Bethesda, MD: NICHD.

4 National Research Council and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development, Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

5 Blank, Helen, Karen Schulman and Danielle Ewen, Key Facts: Essential Information About Child Care, Early Education, and School-Age Care, Washington, DC: Children’s Defense Fund, 1999.

6 Peth-Pierce, Robin. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care. These conclusions are based on a national sample of 1,364 children from across the economic spectrum. Comparisons were of high quality care — as determined by the researchers — delivered at organized centers and all other arrangements except care delivered by a mother at home. The Abecedarian Project at the University of North Carolina found similar patterns in a smaller group over a longer time.

7 Peth-Pierce, Robin. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care.

8 Dahlburg, John-Thor, “Maternal Schools rear France’s littlest students; California is Studying the French system of virtually universal state-subsidized education for children as young as 2 years old,” Los Angeles Times, page A3, 8/15/99.

9 Even in a state with high housing costs, like California, families with more than one child in care while parents work are likely to spend more for that care than for their housing, cited in Pearce, Diana and Brooks, Jennifer, The Self-Sufficiency Standard for California, San Francisco: Equal Rights Advocates, 2000.

10 Peth-Pierce, NICHD Study of Early Child Care.

11 The Nexis database is comprehensive, but not always complete. So we cannot be certain of having captured every relevant story.

12 Since most articles dealing with the issue of child care appeared in the home edition, very few substantive child care stories were excluded by this condition.

13 The sample was stratified by date with a random start for all but the Bakersfield paper. The Californian’s data base did not permit easy isolation of stories by topic, so no sampling frame was possible. Instead we examined half of the articles electronically available for the two-year period, taking all of the substantive child care stories in both business and other sections.

14 Moss, Steven. The Economic Impact of the Child Care Industry in California. Oakland, CA: National Economic Development and Law Center, Fall 2001.

15 Smith, Kristen. Who’s Minding the kids? Child care arrangements, Current Population Reports, Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, 10/2000.

16 McManus, John and Lori Dorfman. Issue 9: Youth and Violence in California Newspapers. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Media Studies Group, 2000.

17 Tribune stories bore no identification of section in the paper’s electronic archive, the only one available for the dates of our study.

18 All stories were considered business stories given the nature of the paper.

19 Totals do not equal 100 due to rounding.

20 Intercoder agreement on topics (in both business stories and others) was .752, calculated using Scott’s Pi, a chance-corrected measure of reliability.

21 The largest margin of error for any of these point estimates is plus or minus 3.4 percentage points, at the .05 level (meaning that the true population mean should fall within this margin of error 19 out of 20 times).

22 The framing analysis averaged .92 agreement, using Scott’s Pi, with a range from 1.0 to .734. Frames failing to reach .7 were rejected as unreliable.

23 The largest margin of error surrounding any of these point estimates is plus or minus 3.5 percentage points at the .05 confidence level.

24 Intercoder agreement for the source analysis averaged .877 using Scott’s Pi. The range was 1.0 to .686. Only one case fell below .70 on the measure.

25 The largest margin of error around any of these point estimates is plus or minus 3.6 percentage points, at the .05 confidence level.

26 Reliability is questionable, Scott’s Pi is .686, under the desirable range of >.70.

27 Reliability is questionable; overall agreement was high (Scott’s Pi=.957) but coders disagreed in the few times either found the source present in the story.

28 Dorfman, Lori and Katie Woodruff. Issue 7, Child Care Coverage in U.S. Newspapers, Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Media Studies Group, 1999.

29 Pittman, Jennifer. The enterprise of child care goes beyond caring for children. Santa Cruz Sentinel, May 3, 2000, page A1.

30 For more ideas, see Wallack L, Woodruff K, Dorfman L, and Diaz, I. News for a Change: An advocates’ guide to working with the media, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1999.

31 Shellenbarger, Sue. Work & Family, Here’s the Bottom Line. Wall Street Journal, June 23, 1999, page B1.

32 Walsh, Mary Williams. Seeking the right child care formula. New York Times, September 13, 2000, page G1.

33 Moss, Steven. The Economic Impact of the Child Care Industry in California. Oakland, CA: National Economic Development and Law Center, Fall 2001.