Issue 13: Distracted by drama: How California newspapers portray intimate partner violence

Wednesday, January 01, 2003As a wannabe policeman, Dan McGovern had to know the two officers would riddle him with bullets when he pulled a .45 caliber pistol out of his waistband in the chill dark of a February morning and pointed it at them.

The patrolmen were waiting to arrest McGovern at his apartment after he had fractured the skull of his Russian mail-order bride. Eight police trigger pulls later the 42-year-old mechanic lay dead.

Two mornings later the San Jose Mercury News would tell his story. It would not be an account of domestic violence, however, but a love story.

"This is the story of Dan McGovern," it began, "who friends and family say, loved cars, cops, guns and most of all, the woman he met after paying $3,000 to a professional matchmaking service."1

The article barely mentioned domestic violence. Rather it portrayed a simple, but good man, driven to apparent suicide by his consuming love for a manipulative foreign bride who done him wrong.

Breathing new life into old stereotypes

Advocates for battered women began calling the Mercury News just hours after the paper hit their doorsteps in February 2001. The dramatic front-page story, they charged, reinforced warped stereotypes about violence between intimate partners: directing sympathy to the batterer and disparaging the victim.

"I heard some people react to this story that maybe she [the wife] tricked him to get over here," said Rolanda Pierre-Dixon, the attorney who leads the domestic violence unit at the Santa Clara County Prosecutors Office. "People were saying, 'what a great guy!' and 'geez, he finally met the love of his life and she deserted him.'"2

"If I'm a woman and I'm getting beaten, and I read this story, it's tremendously negative because my batterer is telling me all the time no one would believe me," fumed Lisa Breen Strickland, executive director of the Support Network for Battered Women in Mountain View.

"There are social norms that support domestic violence," explained Janet Carter, managing director of the Family Violence Prevention Fund in San Francisco. Among them: "this is a normal part of marriage...a family affair...he was so angry he couldn't help it...there must be a reason he did this. The press reflects this. The public thinks, 'if she would just change her behavior,' rather than if he would just change his behavior."

"It's not a love story when a man beats a woman so seriously that she goes to the hospital with severe head injuries," Mercury News reporter Michelle Guido complained.

Even before the first calls rang in the newsroom, the editor who signed off on the story had second thoughts. "I confess I just dropped the ball," said Marc Brown. The following day he picked it up. The Mercury News published a second story about the McGovern case. It said even broken-hearted men don't get to crack the skulls of the women they love.

Intimate partner violence in the news

How news media tell the story of intimate partner violence (IPV) will have a profound effect on what our society decides to do about it. News both reflects and shapes public attitudes — and these can stimulate or stymie policies that might remedy spousal and dating violence. So it is important to discover whether the issue is overlooked or distorted in the press.

Violence between those who are or have been in a romantic or sexual relationship is a vast public health problem. The American Journal of Preventive Medicine reports:

The proportion of women experiencing IPV during a lifetime has been estimated from 25.5% to 40%, and as high as 53.6% when including psychological/emotional abuse. IPV has been reported as the most common cause of nonfatal injury to women in the United States, as well as a major source of healthcare utilization and cost, serious chronic health problems or poor physical health and psychological problems or poor mental health.3

Such violence is also the most frequent felony arrest in many jurisdictions.4 On average, more than three women are murdered by their boyfriends or husbands every day in the U.S.5 While women are disproportionately the victims and males the perpetrators, IPV also refers to male victims and same-gender couples.

Beyond the toll on millions of victims' physical and mental health, IPV also correlates with child abuse.6 Batterers often don't stop with spouses. And because children are frequently present when spouses are abused, young ones become 7 to 15 times more likely than nonexposed children to abuse partners when they become adults.7 Without intervention, domestic violence perpetuates itself.

Battered women's advocates and feminist scholars8 have complained about how such violence has been portrayed for more than a decade. But because such research has been anecdotal — focusing on one case or another — the extent that U.S. news media downplay violence against women or shift responsibility from perpetrators to victims has been difficult to judge. Was the Mercury News'first story about Dan McGovern, the good guy gone wrong, typical? Or was the follow-up story that put the incident in the context of IPV more representative of news coverage? We decided to find out by examining a year's worth of articles in two major newspapers to discover how contemporary reporting portrays IPV.

Method

We analyzed how violence is reported at a regionally and nationally prominent newspaper, respectively the San Jose Mercury News and the Los Angeles Times.9 In addition to their influence on journalistic practice, we selected these papers because they are located in counties with domestic violence death review teams. These teams collect data that allowed us to compare rates of IPV coverage with the incidence of homicide between current or former partners.

Using the electronic databases NewsBank (for the Mercury News) and Nexis (for the Times), we identified more than 5,200 articles about criminal violence10 occurring in the U.S. and published in 2000.11 We printed and analyzed every story about IPV (488 articles). Conforming to the U.S. Justice Department's National Violence Against Women Survey classification, we defined IPV as that taking place between current or former romantic/sexual partners, including those on an initial date. We also gathered a random 1-in-9 sample of all other violence stories. That sample, comprising 529 articles, was ordered chronologically over the 12 months.12

How is IPV depicted in newspapers? How does that compare to coverage of other types of violence?

To assess how IPV is portrayed and whether coverage of IPV differs from reporting about other kinds of violence we created four measures to determine:

- whether IPV got press attention commensurate with its frequency as an arrest in 2000;

- when IPV was covered, whether the quality of reporting differed from coverage of other violence;

- whether news coverage misrepresented IPV as more lethal than it is; and

- whether IPV reporting was more or less murder-oriented than coverage of other kinds of violent crimes.

First we looked at the number of IPV stories per IPV arrest in Santa Clara County (the primary circulation area of the Mercury News) and Los Angeles County (the primary circulation area of the Times) and compared that ratio with the number of stories per arrest for other violence. We included all stories about these violent incidents that occurred in the home counties as well as any thematic stories that were originated by the papers' own staffs.

Next, we examined whether IPV received the same quality of coverage as other kinds of violence. Media effects researchers have found thematic reporting — stories that look at issues or patterns of events rather than focusing on a particular episode or incident — is often substantially more helpful to readers as a resource for making sense of events.13 Episodic reporting, on the other hand, may lose sight of the forest for the trees. So we calculated the percentage of all stories that were thematic for both intimate and other violence samples.

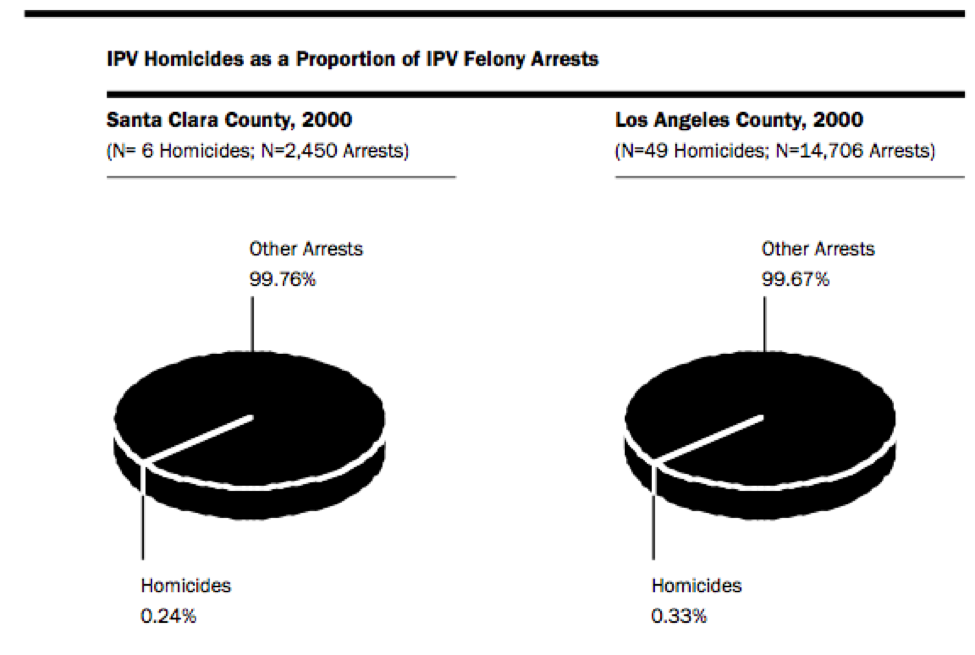

To measure the "murder-centricity" of coverage, ideally we would have liked to calculate the percentage of all IPV incidents that involved murder and compare that with the percentage of all news stories about IPV that described a murder. But California does not keep records of IPV incidents — only arrests.14 So we were forced to use arrests as a surrogate for incidents. Using arrest and homicide data for Santa Clara and Los Angeles counties, we calculated the ratio of IPV homicides to all IPV felony arrests and compared it to the ratio of IPV murder stories to all articles about IPV.15 We calculated the same ratios for non-IPV homicides and felony arrests as well. These ratios allow us to compare IPV to other violence coverage. To be sure we were comparing apples to apples, we only counted news stories about violent incidents within the home counties.

Are victims blamed in news coverage of IPV? Is blame mitigated for suspects?

To answer these questions, we employed a frame analysis. A frame is a theme or sometimes just a cue that activates a scenario in the minds of some readers. For example, alluding to a victim's "affair" may imply some responsibility for ensuing domestic violence. Frames are powerful because they aid certain interpretations and hinder others — usually without the reader's awareness. Frames create tracks for a train of thought.

To determine which frames to include in our study, we examined the research literature and interviewed reporters who cover IPV and advocates for battered women. With their guidance, we developed a coding instrument that included frames describing the different ways in which victim-blame might appear in the news. We looked for frames suggesting that the victim contributed to the violence by wearing suggestive clothing, flirting with others, or other behavior; by physically provoking her attacker; by being "unfaithful" or dating others; by drinking or doing drugs; by staying with a violent partner; or by taking some other action.

For suspects, we examined, first, the finding in the literature that the suspect's identity was often obscured and the focus shifted to the victim. Second, we looked for frames that let the perpetrator off the hook, either partly or completely. Third, we tested the claim that the couple is blamed for the man's abuse. Finally, to be fair to journalists, we also looked for frames that held the suspect's feet to the fire — by attributing the violence to the suspect's controlling behavior, for instance, or by rejecting blame-shifting, e.g., "there's no excuse for domestic violence." For both IPV and other violence we measured whether suspects were identified, and how much vis-à-vis victims. We looked for identifiers such as name, age, residence, occupation, education level, achievements, etc. and computed one total for the suspect and another for the victim.

In looking for themes that might deflect blame from the perpetrator, we again consulted both research and battered women's advocates. They described a tendency to excuse the batterer by arguing that he was drunk (and thus "less responsible" for his actions); or that he "snapped," acting out of character; or that he was prompted by passion or love, or by an attempt to save the relationship or keep his children. We also looked for outright claims of innocence.

For the IPV articles alone, the lead researcher re-read the stories in which we found blame or mitigation frames to determine whether they explicitly or implicitly assigned responsibility. If explicit, he examined the gender of the victim and whether the frame was challenged or contradicted — which might lessen its ideological impact. Explicit frames causally link a prior behavior or motivation with violence. "A" happened because of "B." Implicit frames mention a prior behavior, but don't expressly connect it to the violence. "A" happened; earlier "B" occurred.

Most frame analyses avoid implied frames because they are less obvious to coders and thus less likely to meet criteria for reliability (agreement between coders). But we included them because the criticisms we tested came from qualitative studies that would be sensitive to implication; we couldn't assess their claims fairly using only obvious indicators. We also think the decisions — conscious and otherwise — that reporters and editors make to include certain information and exclude other elements often reveal a subtle causal logic. News is a terse and "objective" genre in which extraneous content is stripped away. Why, for example, include a comment about a woman's remaining with a violent man in a story of abuse if journalists don't judge it relevant to the violence?

To be sure the frame was really identifiable in the text, we randomly selected 20%, of both the IPV stories and other violence stories, which a second researcher coded independently of the first. We calculated the percentage of agreement between the two for each measure, as well as a reliability statistic that corrects for agreement based merely on chance. Measures not meeting criteria for reliability were dropped from the analysis.16

Findings

Compared to other violence, IPV did not get press attention commensurate with its frequency as an arrest

The Mercury News reported 17 thematic stories about intimate violence plus 38 episodic articles about such violence in Santa Clara County for a total of 55. There were 2,450 IPV arrests in the county in 2000,17 so the story per arrest ratio is .0224. Our sample of stories about other kinds of violence in the Mercury News contained 24 thematic stories plus 35 episodic stories describing such violence in the county, for a total of 59. Since each of the other violence stories represents 9 articles in the paper, we estimate that the paper reported 531 stories about other violence that occurred in Santa Clara County. There were 2,952 arrests for other types of violence, which yields a story per arrest ratio of .1799. That's 8 times larger than the ratio for IPV stories.

Even if you account for the largest margin of error around the ratio for other violence, the gap would only shrink to 6.4 times as many other violence as IPV stories.18

The Times staff wrote 21 IPV thematics plus 82 county episodics for a total of 103. There were 14,706 IPV arrests in LA County in 2000,19 so the ratio of story per arrest is .007. For the other violence sample, the Times produced 105 thematics and 116 episodics for a sample of 221. Multiplied by 9, the total comes to 1,989 stories. There were 25,734 other violence felony arrests in the county, so the story per arrest ratio is .0773. That's 11 times larger than the IPV ratio. The maximum margin of error would only reduce the ratio to 10.2 times as many other violence as IPV stories.

In terms of coverage per arrest, our data clearly show that in both newspapers intimate partner violence didn't get even the same minimal coverage that other violence got.

Compared to other violence, IPV was treated less frequently as an issue

When we counted all violence articles in the papers, including stories from wire services such as the Associated Press, only one-in-eight intimate partner violence stories rated treatment as an issue, trend or theme rather than as a simple description of a particular violent episode. In contrast, a third of all stories about other violence were thematic.20 The relative lack of thematic coverage of IPV indicates that it was rarely the topic of enterprise reporting — stories journalists originate to answer the public's broad questions about current issues and events — or policy/government reporting, which is almost always issue-oriented.

IPV was presented as more lethal than it is

In Santa Clara County there were only 6 IPV homicides compared to 2,450 IPV arrests — a ratio of 1?4 of 1% .21 In Los Angeles County there were 49 IPV homicides compared to 14,706 IPV arrests — a ratio of 1/3 of 1%.22

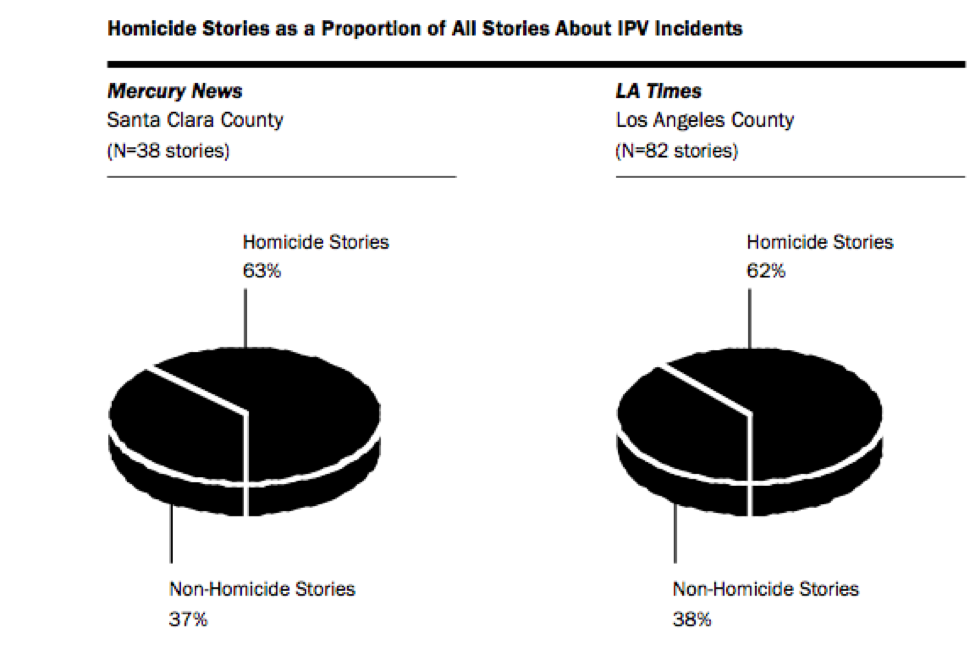

The news coverage presented a very different picture. Fully 63% of the Mercury News' total of 38 stories about IPV in Santa Clara County concerned homicide. Six homicides rated 24 articles while 2,450 arrests for IPV felonies elicited just 14 stories — a tad more than 1 per month. The Times IPV reporting was also extremely "murder-centric." Articles about homicides constituted 62% of all 82 stories about cases of IPV occurring in Los Angeles County.23

Put another way, the Mercury News published only one story describing IPV other than murder for every 175 felony arrests for IPV in Santa Clara County. In the Times, the ratio was 1 non-homicide story per 475 IPV arrests in Los Angeles County. Both newspapers grossly distort the nature of IPV by portraying it almost exclusively at its most extreme level.

IPV coverage is more murder-oriented than other violence coverage

It is well known that homicides are covered disproportionately by news media.24 But the pattern was even more extreme for IPV. While 63% of all Mercury News stories about IPV in Santa Clara County described murders, the ratio of murders per IPV felony arrest was just 2.4 for every 1000. Thus the proportion of murder stories to all IPV articles exaggerates the ratio of murders to felony arrests by .63/.0024 or 263 times. The same analysis for other violence stories shows that 37% of all Mercury News articles concerned homicide. County records show 24 murders for other violence compared to 2,952 arrests for a ratio of 9.5 homicides per thousand felony arrests. So the proportion of murder stories to all other violence articles exaggerates the ratio of murders to felony arrests by .37/.0095 or 39 times. Therefore, coverage of IPV emphasizes murder 263/39, or almost 7 times more than coverage of other violence. Even at the greatest margin of error for the other violence sample, coverage of IPV is about 5 times more murder-centric.

Similarly at the Times, the 62% of all LA County IPV stories concerning murder compares to a ratio of 3.3 murders per thousand IPV felony arrests. Dividing .62 by .0033, we see that IPV murders were exaggerated over violence short of murder by a factor of 188. For other violence, 61% of all stories concerned murder. There were 951 murders not involving intimate partners in the county in 2000 compared to 25,734 felony arrests for such non-intimate violence, a rate of .037. So the portrayal of murder exaggerates its incidence by .61/.037, about 17-fold. Thus, IPV coverage is 188/17 or 11 times more murder-oriented than other violence reporting. Even at the greatest margin of error for the other violence sample, IPV coverage is 10 times more murdercentric.

If homicide is the only IPV worthy of coverage, journalists are exposing just the tip of an enormous and threatening social pathology. IPV is homicidal less frequently than other types of violent crime.25 Yet in many American cities, police make more arrests and answer more 911 calls about domestic violence than any other kind of violent offense.26 The magnitude of the problem wasn't reflected in these two newspapers.

IPV reporting rarely blames the victim, but does so more than other violence reporting.

Overall, we found few instances of blaming the victim in IPV stories — no specific frame appeared in more than 5% of such stories. Only one approached that level — the notion that the victim contributed to the violence by staying in a violent relationship. Still we did find occasional victim blame in the IPV stories. In contrast, our sample of stories describing other types of violence turned up almost no victim-blame at all.

Table 1 shows the frames previous research suggested would be most common, an example of how the frame was expressed in news stories, and the percentage of IPV stories in which the frame appeared.

The pattern of blaming a female victim for IPV that we expected from prior research was barely detectable in these two newspapers. Almost half of the victims blamed turned out to be male. These frames shifted blame away from female assailants. We also found that female victim-blame statements were sometimes contradicted or challenged in the same article, likely lessening the strength of the blame frame.

The most frequent victim-blame frame was staying with a violent partner. Although this frame appeared in 24 stories, it was explicit in only 7. In 3 of the 7 explicit uses, the frame was challenged. For example, in a Times column in which a student blames her girlfriends who continue to date abusive boys, the columnist then quotes the teacher responding: "I won't accept that anyone likes getting beat up." Rather than becoming a reinforcement of a stereotype, it became an opportunity to undermine its legitimacy.

Overall, our results turned up some victim blame directed at women, but not much. Even if we aggregate such frames and add up all of the articles in which blame was explicit, uncontested and directed against female victims, they constitute less than 4% of the 488 analyzed.27 In our parallel analysis of 529 stories describing other kinds of violent crime, we looked for victim blame frames such as victims entering dangerous places, flaunting wealth, failing to heed warning signs of danger, becoming impaired through drinking or drug use, failing to cooperate with police, appearing vulnerable, etc. Only one frame registered in more than 2% of the articles sampled28 — "the victim provoked the violence with a physical attack" — which appeared in 8.5% of stories. Even our catchall frame of any other victim blame statements appeared in just 2% of sampled stories.

Our analysis of reporting in two large quality newspapers does not support the implication in the literature that blaming women for IPV is common; at these papers it was rare. On the other hand, victims of IPV are still blamed more often in news coverage than victims of other types of violence. In other types of violence news, victim-blame was almost non-existent, except for physical provocation.

IPV reporting rarely deflects responsibility from the batterer, but does so more than other violence does.

Most earlier research indicated that male suspects are frequently excused from at least some responsibility for their assaults. Again our results differed. Although more common than victim-blame, shifting blame away from suspects was rare and often merely implied. Further, frames squarely blaming the suspect were about as common as those deflecting responsibility. There was one exception to the pattern: a high number of claims of innocence by suspects, more than 90% of which were associated with trials. Many were pro forma "not guilty" pleas.

Batterers' identities are not obscured

Far from being obscured, we found that reporters consistently named IPV suspects and identified them more completely (averaging 3.17 attributes) than victims (averaging 1.93). In fact, both papers appeared to have a policy not to identify any victim of a sexual assault. Sometimes the names of other IPV victims were also withheld. Even in murder cases — when the victim can no longer suffer embarrassment — suspects were better described than victims, although the gap narrowed.

The practice of reporting more fully on suspects than their victims was not unique to IPV, however. Suspects were significantly better identified in the sample of stories containing reports of other kinds of violence as well, although the difference was about half as great.36 Perhaps because they are more threatening, suspects are considered more newsworthy than victims.37

Perpetrators are rarely excused

Table 2 summarizes our findings showing that perpetrators are rarely excused in news coverage of IPV.

Again, when we looked more closely at the context of these frames, we saw they were often challenged. The "perpetrator snapped" frame, for example, was usually explicit (in 15 articles of 21). But in all but 3 of the explicit stories describing the violence as an uncharacteristic lapse of control the frame was contested. In addition, 3 articles contained the reverse of the frame. An example of this opposite frame was found in a Mercury News book review: "Murray makes it clear that abuse is not a natural reaction; it's deliberate. 'His hand doesn't just jump out of his pocket and slap her in the face,' Murray said during an interview, 'They don't act out of anger, but out of a need for dominance and control.'"38

The most common mitigation frame, that both partners bear some responsibility, was usually implied (31 of 47 articles). In the 16 stories with explicit uses, the preponderance of blame was levied on men in 11, on women in 2 and on both parties equally in 3. Blame usually took the shape of criminal charges. For example, although San Diego Padres outfielder Al Martin was described as having "exchanged punches" with a woman who claimed to be his wife, only he was charged with assault.39 In the two cases where women were blamed, police were investigating them for murders.

If we sum all explicit uses of these four mitigation frames in which the batterer is male, we find the expectation of the research literature met in only 14 articles of 488, about 3%.

In addition to mitigation frames, we also saw outright innocent pleas. As trial coverage comprised a large part of both papers' reporting of IPV, this frame was prominent — appearing in 120 stories, or 24.6% of all IPV articles. Most were connected in some way to a trial. Whether the invocation of this frame represents an attempt to deflect blame from IPV suspects depends on whether it occurs more often in these stories than in reporting of other types of violent crime. As we shall see, it doesn't.

Batterers are blamed

To be fair to the press, we also looked for several counter-stereotypical frames — those holding the assailant responsible. We found these frames — all of which counter the expectation in the research literature — to be at least as common as suspect-mitigation themes. They are summarized in Table 3.

By far the most common counter-stereotype described bullying, controlling behavior.

This relatively common frame was most often explicit — described as a cause of the violence in 40 of 53 stories. It was also overwhelmingly directed at male perpetrators.

Mitigating factors are rarer still in coverage of other violence

Our analysis of stories describing other kinds of criminal violence turned up some parallel frames; five are of interest.

The possible mitigation frame of impairment due to alcohol or drug consumption showed up in 4.2% of articles — almost as often in other violence stories as in those describing IPV.48 That squares with research findings showing that alcohol use accompanies both domestic and other kinds of violence.49

However, the snapped or "acting out of character" frame was very rare, appearing in 1.5% of other violence stories. That's much less than in IPV stories even when sampling error is accounted for.50 The difference suggests that the stereotype uniquely attaches to IPV. But the frequent challenge of this frame demonstrates that journalists are not merely transcribing it verbatim from sources.

The bullying/controlling frame appears in 4% of the other violence stories — less than half as often as in IPV articles.51 But one would expect this frame to be less frequent given the wider range of criminal situations in the other violence sample.

The innocence claim52 appears slightly more frequently in other violence stories than in IPV articles, even when margin of error is considered.53 Were reporters using the frame to shield batterers we'd expect it to be more common in IPV coverage.

Finally, the both-sides blame frame — analogous to the couple blame frame in IPV reporting — appeared in 30 stories of 529 sampled (5.7%). Sampling error could narrow the gap, but this falls significantly below its frequency in IPV stories (9.6%).54 The fact that all IPV arises from relationships while fewer victims of other kinds of crime know their assailants may invite the claim that both parties are at least partly to blame for much IPV. As we saw, that claim is often refuted in the same story, but sometimes advanced to lessen blame on a perpetrator of violence.

Our analysis finds little support for the idea that male suspects are often excused or their responsibility diminished in IPV stories published in the newspapers studied. Few stories contain frames that might mitigate responsibility. When such frames do appear, they are frequently challenged or used in a context that doesn't reduce blame.

On the other hand, the "snapped" frame barely exists when reporters are describing other kinds of violent crime. And the concept of "no excuse" for spousal abuse is rarely invoked in IPV coverage. Also, both sides are more often blamed in intimate than other violence stories. Perhaps the data signal changing practice in the newsroom:

Stereotypical frames are used, but contested, rather than included without question as they might have been in the past, or considered irrelevant as they might be in the future.

Conclusion

The key finding from this study was that most IPV goes unreported, even in high quality newspapers. Readers see only the most extreme cases. The absence of reporting about nonhomicidal IPV distorts the picture, making it more difficult for families and citizens to understand and address the problem. But when IPV is reported, the most blatant sexist stereotypes, at least in these two papers, rarely appear.

The present study may have found low levels of victim blame and suspect mitigation not because such themes are gradually disappearing from press accounts of IPV, but because of the quality and location of the newspapers we analyzed. Both the Mercury News and the Times are recognized among journalists as among the nation's best newspapers.55 Further, with their domestic violence death review committees, police and other officials in Santa Clara and Los Angeles counties may be more progressive in coping with IPV than other parts of the nation. Therefore, generalizations to other news media and to those in other regions merit caution.

Looking over a year's worth of reporting about violence — intimate and other — and talking to reporters, editors, scholars, and women's advocates, we think the way IPV is reported is undergoing an important shift. As more women enter the newsroom and move into leadership positions in journalism,56 the press is becoming more sensitive to IPV,57 even if it still doesn't report it even as sketchily as it covers other violent crimes. Feminists and activist groups, such as the Family Violence Prevention Fund, have helped raise consciousness and put the problem on the political agenda. They convinced Congress to pass the Violence Against Women Act in 1994. Over the last few decades, gender roles have broadened. Together these forces are pushing society to recognize the unique challenges of IPV, its prevalence across ethnic and economic boundaries, and the damage it wreaks among not just women, but children, co-workers and others trapped when violence occurs. IPV is gradually becoming understood as an issue affecting the community as a whole, rather than as a women's or private family problem.

It's useful to recall that intimate partner violence has only recently been considered a crime in the eyes of the law. It's just beginning to be counted in state crime reports and has yet to crack the FBI's Uniform Crime Report. The recognition of domestic violence as a social problem only occurred in the United States three decades ago.58 In many parts of the world, beating a spouse is still considered a family matter. As our approach to IPV shifts from private matter to public criminal matter, to public health issue worthy of intervention and prevention, coverage will likely shift as well. News both reflects and shapes social norms.

While critical of the Mercury News'coverage of Dan McGovern's final night, Ms. Strickland of the Support Network for Battered Women conceded: "Seventeen years ago domestic violence didn't get reported in newspapers at all, unless it was the most horrific cases. So we've come a tremendous distance. Overall, I think reporting has improved as our social norms have changed."

Recommendations

Since most of the IPV that happens in a community is not covered, the public does not get a complete picture of the problem. The acts of IPV that finally draw reporters' attention are typically the result of a long pattern of dominance and control. Bringing this picture into focus will be challenging, however, since news media will not be able to report on every incident — just as they can't report on every incident of other violence. Those who write about IPV and those who are trying to do something about it both can contribute to improving coverage. We offer the following suggestions for reporters and editors, and for their sources: those in public health and other agencies who are working to prevent IPV.

Recommendations for reporters and editors

Print, broadcast and web journalists who hope to help the public make sense of and cure the widespread plague of IPV face two tasks. First, they must report on partner abuse as the significant, costly and tragic social — rather than personal or family — problem that it is. And, they must avoid inaccurate stereotypes of such violence that subtly or otherwise shift blame from perpetrators to victims. Based on this research, the more difficult task will be bringing typical, rather than extreme, cases of IPV into the news along with a focus on causes, interventions and prevention.

Task #1: Bring the larger picture of IPV into focus

News organizations cannot report on each of thousands of IPV incidents that occur each year in their communities or there would be little else covered. So, the question becomes, how can journalists bring the larger picture into focus within the constraints of daily news? The challenge is to find mechanisms beyond the occasional in-depth series that, though they can be excellent, appear infrequently. Newspapers, for example, have managed to draw more expansive pictures on other beats. Reporters covering politics, business, entertainment — even sports — depict both the unusual and usual events of the day. The crime beat in general — and IPV coverage in particular — is far behind in this regard, and due for some retooling.

A few suggestions:

- Name it. The public doesn't know just how common IPV is not only because it's rarely covered unless it turns murderous, but because reporters don't label it, say advocates and journalists alike. Naming something is important, says Janet Carter of the Family Violence Prevention Fund. "The more you see the same thing the more you see how common it is. If you report it under different names, people can't see a pattern." In a single sentence reporters can label a particular incident as the Nth case of IPV this year in a particular city or county.

- Enterprise IPV. Mercury News reporter Michelle Guido, who wrote a groundbreaking series on domestic violence, says ideally a reporter would "get out in the community and hang out with cops [assigned to] domestic violence, and advocates, and go to training classes, [talk to] probation officers, [attend] batterers' classes. Do what we did when we did our series." This will help reporters be prepared to broaden coverage from incidents to issues. "The dead and the near-dead is [the only thing] they want to talk about," says Santa Clara County Assistant District Attorney Rolanda Pierre-Dixon, who specializes in domestic violence prosecutions. She wouldn't welcome a flood of reporting about less severe cases, however. "I'm not about any individual case," she explains. "Education. Take the opportunity to educate people. I'd rather they talk more about the generalities of domestic violence, how to recognize it. I want more prevention stuff, more intervention stuff. What women can do. What's available? What are people doing [about] services, treatment, language barriers, lack of shelters? I have yet to see a story about what happens in a women's support group. There's very little on batterers' treatment success. When is it covered as an issue?"

- Recognize and include risk factors for IPV in spot news. If reporters asked about the frequency of the type of crime, whether drinking or drugs were involved, about previous violence by the suspect, prior safety efforts by the victim, about how a gun was obtained, about the effects on children who witness the violence, about costs — not just trauma, but medical, police, court, and lost family income — the public would see the crime with greater fidelity. If reporters stated laws regarding battering, potential victims could understand their rights. Even at good papers like the Mercury News and Times, these questions were seldom answered.

- Point readers to local resources. If community resources and hot lines were listed, available services could be more fully utilized. Include a resource box or graphic that lists contact information for local agencies prepared to help batterers and their victims with an IPV story once a month. Remind readers and viewers that while the circumstances surrounding each incident may differ, the violence has predictable warning signs. Most IPV that ends in homicide escalates over time from acts of domination and control.

Task #2: Avoid myths and stereotypes

Our findings are promising; there was little evidence that two high-quality newspapers perpetuate the usual stereotypes about IPV. We did find victim-blame and suspect-mitigation on occasion, and caution that news media in other regions may continue to employ them. Editors should be alert for them and encourage reporters to:

- Keep digging if the suspected batterer is described as a "nice guy." The first acquaintance a reporter asks about the suspect's personality might well volunteer that "he's a nice guy," says Lisa Breen Strickland, of the Support Network for Battered Women. That's what happened to Ms. Guido reporting about a local policeman who ran his girlfriend's car off the road and then shot her to death. But inquiring further she found others who knew the officer well considered him a bully.

- Apply the research. Studies show the most dangerous time for a woman is during or just after an attempt to leave an abusive partner.59 "When people ask, 'why doesn't she leave?', that's naïve," says Ms. Guido. "People have a hard time sympathizing with victims of domestic violence. Their visceral reaction is 'get out!' [They think] 'I would get out.'" There may be research findings that apply to the issue, or local patterns. One of the major findings of Ms. Guido's 1999 series on domestic violence was that police are ineffective at protecting women who testify against their attackers. "Thousands who are arrested and convicted in the Bay Area each year are sent to probation departments that are ill-equipped to closely monitor whether offenders return to battering their victims,"60 she (and staff writer Carole Rafferty) reported. To blame a victim for failure to leave or press charges under such circumstances misapprehends the risk.

- Add new sources to the mix. If a battered woman doesn't speak up for herself, her side of the story is unor under-reported, says Ms. Strickland.61 Reporters want to speak with victims because "the best story comes from those willing and able to talk [but] most victims [of IPV] aren't willing...It's just not safe," she explains. "It's all about power and control. If the victim is talking to the press, then [the batterer] has totally lost control." The solution? Consider calling a battered women's advocate. "We have trained many women who are former victims to give voice to a story their [recently battered] sisters can't," says Ms. Strickland.

- Counter stereotypical quotes. The tenets of journalistic objectivity require reporters to build stories around the comments of sources. But journalists are interpreters of reality, not stenographers. They routinely assess the credibility of source comments, filtering out what seems either irrelevant or greatly at variance with other information they've gathered or their prior understandings of how things work. Sometimes, however, reporters may not be able to avoid quotes containing inaccurate stereotypes. If authorities or key actors in a story use such clichés, a reporter who ignores them may miss an important part of the story. The fact that an authority thinks that way may be newsworthy in itself. In such cases, reporters can carefully attribute the stereotypical comment — making it clear that the words belong to the source — and find other sources to challenge it or present a differing view. At the Times and Mercury News sources such as public health officials, community leaders, battered women's advocates, researchers in the academy and elsewhere, politicians, non-elected government officials, etc. were very rarely quoted.

Taken together, these recommendations suggest that news organizations should adopt a conscious strategy to avoid cultural stereotypes and encourage reporting that serves as a civic resource for reducing IPV. As we have seen, business-as-usual police reporting is insufficient. "The underlying point is that we have to think about these things," Ms. Guido points out. "On deadline there isn't time. We have to think about them in advance."

Recommendations for public health researchers and advocates

The public health data show that IPV incidents usually are not isolated, independent events but are linked to larger social, economic, and political forces. But if journalists are to make those links in news stories, they'll need help from public health epidemiologists and others with access to data and information about trends and prevention — on deadline. The information that contextualizes IPV is often not obvious or easily accessible. Those with the most authentic voice, the victims themselves, are often reluctant to speak with reporters. Public health practitioners and other advocates can help journalists include such information routinely in stories by developing relationships with them, providing data and other resources, and by creating and responding to news about IPV.

- Build relationships with reporters who cover the crime beat.

Become a trusted source so reporters have somewhere to go for data and information that can fill out the context when bad news breaks. Health professionals and members of community-based organizations are among the least quoted sources in IPV stories. To be heard more often in the news, they need to make themselves and their resources known to journalists. This includes providing background on IPV, prevention, "real people" sources, and evidence-based information. Without new sources that actively seek them out, most journalists will rely on their traditional contacts based in the courthouse and the police station. Those sources need to be augmented with others who can talk about new perspectives on prevention, risk factors, and patterns of violence. Public health professionals should provide background and be available when journalists are on tight deadlines with breaking news. - Prepare spokespeople from the public health department and other related agencies to speak to reporters, then give them the opportunity to do so.

If journalists are to add new sources to their mix, the new sources have to be ready and willing to talk. Health departments and other groups can provide training to researchers and advocates, so they can speak confidently about local violence trends and the work they are doing to improve their communities for themselves and others. Reporters will get the most vivid picture of prevention efforts if they hear directly from the people conducting them. And, public health practitioners can include members of the community in training and events where they can meet reporters and build relationships with them, particularly when those who have suffered from IPV want to come forward and speak. Be sure that when they do, they have the training and support they need to speak effectively. - Share data about IPV.

Reporters can't put IPV in context without local data, and they often need it in a hurry. Honor their deadlines, have fact sheets ready, and be willing to talk. Work to resolve problems with confidentiality and other barriers to sharing information so journalists can learn about local patterns, incorporate that information into daily stories, and give citizens the information they need to make better decisions about prevention and intervention policy. - Create news about IPV that is not linked to homicide.

Pitch stories to reporters throughout the year that focus on action and policy designed to prevent or intervene in IPV. If prevention efforts are working, tell journalists about it. Public health practitioners can learn to recognize the newsworthy aspects of their prevention activities and make contact. Police departments frequently issue news releases and hold news conferences to make statements about specific incidents or trends. Public health can do the same. Reporters can't write about IPV prevention and intervention if public health practitioners don't tell them about it.23 - Use editorial venues.

Write letters to the editor, op-eds, and make editorial board visits anytime news about IPV needs explaining.

The public gets its picture of IPV from the news. If journalists are going to present a more complete picture, public health advocates will have to help. Without a change in reporting about IPV, and the willingness of public health and other advocates to support that process, the chance for widespread understanding of IPV — and a commitment to ending it — will be diminished.

We would like to thank Michelle Guido, a police reporter at the San Jose Mercury News, who consulted on this study, and Visiting Assistant Professor Nancy Berns of Drake University who read and responded to our findings. We are also grateful to the San Jose Mercury News for pro bono access to its electronic news archive. Issue 13 was supported by a grant from The California Wellness Foundation as part of its Violence Prevention Initiative.

Issue 13 was written by John McManus, PhD, and Lori Dorfman, DrPH. Thanks to the hard work on a difficult topic by coders Elena O. Lingas, MPH, Jennifer L. Carlat, Saleena Gupte, MPH, and Karen White. Ms. Lingas also contributed to the analysis and editing.

Issue is edited by Lori Dorfman.

© 2003 Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute

References

1 "Man's Failed Marriage to Russian Bride Was Prelude to Fatal Shooting," Mercury News, 2/28/2001, A1.

2 Comments about the Mercury News story were gathered in interviews during the first week of March, 2001, shortly after the story broke.

3 Joshua R. Vest, Tegan K. Catlin, John J. Chen and Ross C. Brownson, "Multistate Analysis of Factors Associated with Intimate Partner Violence," American Journal of Preventive Medicine 22(3) (2002) 156-164.

4 "The Face of Abuse," San Jose Mercury News, 9/26/1999, A1.

5 Callie Marie Rennison, "Special Report, Intimate Partner Violence and Age of Victim, 1993-99," (U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC, October 2001).

6 Rosemary Chalk and Patricia A. King, ed. Violence in Families: Assessing Prevention and Treatment Programs (Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1998).

7 J. Kaufman and E. Zigler, "Do Abused Children Become Abusive Parents?" American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 57(2), (1987): 186-192, cited in Chalk and King, Ibid.

8 Georgia State Professor Marian Meyers argues that "only within the past 15 years, have researchers combined feminist theory about violence against women with studies of news coverage" (p. 28). See Marian Meyers, News Coverage of Violence Against Women: Engendering Blame (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1997).

9 Our funding source limited us to California newspapers. However, as the largest — and arguably most media-genic — state, California powerfully influences the national culture.

10 We defined such violence as "a deliberate physical attack on a person, including violence to self and self-defense, or a written or verbal threat of bodily harm, or stalking, harassing, or otherwise menacing an individual's physical person." We chose this definition because it parallels the one used by the National Violence Against Women Survey sponsored by the U.S. Justice Department and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

11 We chose 2000 because more recent state crime statistics were not available.

12 That assured us equal numbers of fat Sunday editions and thin Monday papers and diminished the distortion of a major violent event occurring at one point in time. Researchers have found such constructed week designs provide the best picture of reporting. See Daniel Riffe, Charles F. Aust and Stephen R. Lacy, "The Effectiveness of Random, Consecutive Day and Constructed Week Sampling in Newspaper Content Analysis," Journalism Quarterly, 70(1) (1993): 133-139.

13 Shanto Iyengar, Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991). Also see Doris Graber, Processing the News: How people Tame the Information Tide (White Plains, NY: Longman, 1984) and Dolf Zillman and Hans-Bernd Brosius, Exemplification in Communication: The Influence of Case Reports on the Perception of Issues (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum, 2000).

14 California keeps track of IPV arrests in a category called spousal abuse. It includes physical violence between people who are married, formerly married, cohabiting or had a child together. It is slightly narrower than our definition of IPV in that it does not include all dating partners.

15 While arrests constitute the best available surrogate for incidents, they substantially underestimate incidents of IPV because most violence between intimates isn't reported to police; see Chalk and King, op cit. Therefore the actual ratio of homicides to less extreme incidents of spousal abuse is smaller than official figures indicate.

16 For manifest or obvious measures, such as whether the suspect was identified by name, we accepted chance-corrected agreements of .8 or better using Scott's pi. For latent measures that required coder judgment, such as the presence or absence of a frame, we accepted pi's of .7 or better. To correct for the conservative bias in pi when one response category is chosen disproportionately, we calculated the correction for chance using the normal polynomial distribution. See W. James Potter and Deborah Levine-Donnerstein, "Rethinking Validity and Reliability in Content Analysis," Journal of Applied Communication Research, 27 (1999) 258-284.

17 Data come from the California Bureau of Criminal Information and Analysis website (http://justice.hdcdojnet.state.ca.us/cjsc_stats). (2/7/2012 update: Link broken. For California criminal justice data, try http://oag.ca.gov/crime.)

18 All margins of error for the other violence sample are calculated at the standard 95% confidence level. Note that the IPV sample has no margin of error since it contains every story in the population.

19 Data from the California Bureau of Criminal Information and Analysis, op cit.

20 The difference is significant at p.001, by a chi-square test of independence.

21 Data come from the Santa Clara County Death Review Committee and the California Bureau of Criminal Information and Analysis website, op cit.

22 Ibid, and a personal communication from Sung Yu, research analyst at the Injury and Violence Prevention Program, Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, 10/2/02.

23 Only 28% of the stories about incidents of IPV at both papers concerned cases within their home counties. The remaining stories describe incidents in the greater Los Angeles or San Francisco Bay Area or elsewhere in California or the U.S. Thematic stories were excluded from this analysis because they could not be classified as homicides or other felonies.

24 Lori Dorfman and Vincent Schiraldi, Off Balance: Youth, Race and Crime in the News (Washington DC: Youth Law Center, 2001); Doris A. Graber, Crime News and the Public (New York: Praeger, 1980); Sanford Sherizen, "Social Creation of Crime News: All the News Fitted to Print" in Charles Winick, ed. Deviance and Mass Media (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1978).

25 In Santa Clara County in 2000, 45% of the felony arrests were for spousal abuse, but only 18% of the homicides. In Los Angeles County, 36% of the felony arrests concerned spousal abuse, but only 5% of the homicides. Non-IPV accounted for a substantially greater ratio of homicides per felony arrest. Data are from the Criminal Justice Statistic Center of the California Department of Justice, available at http://justice.hdcdojnet.state.ca.us/cjsc_stats/prof00/. (2/7/2012 update: Link broken. For California criminal justice data, try http://oag.ca.gov/crime.)

26 In California, police agencies received almost 200,000 calls for help in domestic violence situations and made more than 51,200 felony arrests in 2000, according to the California Department of Justice (http://caag.state.ca.us/cvpc/fs_dv_in_ca.html). Domestic violence was the number one violent felony arrest in the state in 1997, according to the San Jose Mercury News, "The Face of Abuse," 9/26/99, A1. (2/7/2012 update: Link broken. For California criminal justice data, try http://oag.ca.gov/crime.)

27 We are grateful to Nancy Bern, who has conducted research about similar negative stereotypes in magazines, for the suggestion to consider the aggregate impact of blame-shifting frames lest our break-out of many specific frames dissipate their combined influence.

28 The margin of error around the largest of these point estimates is plus or minus 1.2 percentage points.

29 The frames are not mutually exclusive; one story could have multiple frames.

30 "District Attorney Decides Not to Charge Marinovich; Jurisprudence: Insufficient Evidence Found in Investigation of Sexual Assault Case," Times, 6/10/2000, D1.

31 "Wife Gets 52 Years In Husband's Slaying; Courts: Judge Rejects Leniency Plea And Arguments That She Dismembered Spouse Because She Had Been Abused," Times, 2/26/2000, B5.

32 "Common Tactic: Blame Victim. Grisly Slaying: Fremont Man Was Convicted of Manslaughter, Not Murder, in His Wife's Death After Her Behavior Was Questioned at Trial," Mercury News, 4/8/2000, B1.

33 "Starzz Star Azzi Breaks Hand. Chmura Charged with Sexual Assault," Mercury News, 5/16/2000, D2.

34 "Sandy Banks; At-Risk Girls, Mentor Get Together and Get Real," Times, 7/30/2000, E1.

35 "Kennedy tells of threat; jurisprudence: Carruth co-defendant testifies about former NFL player's demands for car, gun," Times, 11/22/2000, D3.

36 On average, suspects were described with 2.59 attributes while victims rated 2.05. The difference is statistically significant at the .05 level. The level of suspect identification, which sums 9 attributes, was marginally reliable in the other violence sample: Intercoder agreement, within 1 attribute, was 85%; Scott's pi was .7.

37 The finding that suspects get more ink than victims isn't new. "Victims of crimes were invisible..." wrote Sanford Sherizen analyzing Chicago crime reporting in the 1970s (Sherizen, op cit, 217). Also see Gabriel Weimann and Thomas Gabor, "Placing the Blame for Crime in Press Reports," Deviant Behavior, 8, (1987): 283-297.

38 "Dating's Ugly Little Secret, Psychotherapist Examines Abusive Teen Relationships," San Jose Mercury News, 10/10/2000, D5.

39 "Spring Training Daily Report; Martin Faces Rough Road," Los Angeles Times, 3/23/2000, D3.

40 "Doctor's Trial in Death of His Pregnant Lover Opens; Courts: What the Prosecution Calls an 'Almost Perfect Murder,' the Defense Says Was Not Premeditated," Times, 11/1/2000, B1.

41 "Man Ruled Sane During Wife's Slaying," Mercury News, 7/29/2000, B4.

42 "Jury Hears Audiotape of Doctor's Confession; Trial: Pasadena Pediatrician Told Homicide Detectives That He 'Just Snapped' and Strangled a Pregnant Colleague," Times, 11/14/2000, B1.

43 "Man Kills Son, Self in Redondo Beach; Violence: Brazilian Cardiologist Wounds another Son. Police Say He Was Despondent About Career and Marriage," Times, 8/8/2000, B3.

44 "County Tries to Break Cycle of Domestic Violence; Early Pioneering Justice System Gives Special Attention to Juveniles Who Batter," Mercury News, 2/25/2000, A1.

45 "California and the West; Killer is First to be Freed During Gov. Davis' Term; Justice: Parole Board Overrides his Objections to the Release of an Oakland Woman who Masterminded the Slaying of her Abusive Boyfriend in 1987," Times, 9/29/2000, A3.

46 This measure was marginally reliable; both coders agreed 92% of the time, but Scott's pi was .58 due to skewness. 47 "Southern California/A News Summary; Ex-Councilman Testifies in His Own Defense" Times, 4/7/2000, B4.

48 The IPV percentage falls within the margin of error of the other violence estimate.

49 James J. Collins and Pamela M. Messerschmidt, "Epidemiology of Alcohol-Related Violence," Alcohol Health & Research World 17(2) (1993): 93-100.

50 Plus or minus 1 percentage point.

51 The margin of error around this estimate — plus or minus 1.7 percentage points — would not come close to closing the gap.

52 This measure was marginally reliable in the other violence sample; coders agreed 88% of the time, but Scott's pi was .66.

53 The margin of error here is plus or minus 4 percentage points, not quite enough to bridge the gap from the estimate of 29.3% of other violence stories with an innocent claim to the 24.6% of IPV stories containing this claim.

54 The margin of error here is plus or minus 2 percentage points.

55 "America's Best Newspapers," Columbia Journalism Review, (November/December 1999).

56 Christy C. Bulkeley, "A Pioneering Generation Marked the Path for Women Journalists," Nieman Reports (Spring 2002) 60-62.

57 We also found that female reporters were almost three times as likely as males to write about IPV as an issue.

58 Ethel Klein, Jacquelyn Campbell, Esta Soler and Marissa Ghez, Ending Domestic Violence: Changing Public Perceptions/Halting the Epidemic (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1997).

59 Rennison, op cit.

60 "The Face of Abuse," San Jose Mercury News, 9/26/99, A1.

61 Immigrant women are particularly vulnerable, says Ms. Carter, of the Family Violence Prevention Fund in San Francisco. "With immigrant women there isn't anyone else whom she [or the press] can talk to. Also there may be cultural barriers, fear of talking to the press or authorities, and language barriers, and lack of family supporting her."