Issue 16: Moving from head to heart: Using media advocacy to talk about affordable housing

Sunday, October 01, 2006This is the story of how a group of dedicated but frustrated affordable housing advocates learned to tell their story so it reflected their values and the values that resonated with policy makers. What they thought would be a simple refresher course in working with the media transformed their own understanding of affordable housing, how to talk about it, and, ultimately, what was done about it.

The story begins in 2003 when Oregon was fast becoming one of the most expensive housing markets in the country. The cost of owning a home in Oregon had been rising dramatically, and in both the cities and rural areas, rents had been rising steadily as well. The growing expense of either owning or renting safe, decent housing was becoming increasingly out of reach for low-income Oregonians. Advocates knew that the need for state and local jurisdictions to provide public funding for affordable housing was more important than ever.

But despite their in-depth knowledge and fierce passion, advocates for affordable housing had been getting nowhere with the Oregon legislature. "We were getting our butts kicked," said Michael Anderson of the Community Development Network, a trade association representing 20 community development corporations in the Portland metropolitan area. Anderson and other advocates, including Janet Byrd of the Neighborhood Partnership Fund, had come to Salem, Oregon's state capital, to promote affordable housing policies during that year's legislative session. But the advocates couldn't even get a committee hearing on any of their proposed bills.

The advocates' primary policy goal was to persuade the state legislature to exempt Portland from a 1989 law that blocks local jurisdictions from instituting Real Estate Transfer Fees. These fees on real estate transactions can serve as an ongoing source of funding for affordable housing. Some advocates believed such a fee could generate $30 million annually in the Portland metropolitan area to help shelter low-income individuals. Yet not all the affordable housing advocates agreed that the Real Estate Transfer Fee should be the primary policy goal. The Housing Lobby Coalition, a group that had joined together to enact Oregon's first Housing Trust Fund in the early 1990's, like Anderson's group, was advocating to preserve Oregon's Housing Trust Fund and to extend the "sunset clause" on the Affordable Housing Tax Credit. But the Housing Lobby Coalition did not support the Real Estate Transfer Fee because it did not believe it was politically feasible.

Paul Rainey, lobbyist for the Association of Oregon Housing Authorities, a collection of 23 statewide agencies that manage public housing and federal rent assistance programs, lamented that housing groups both inside and outside the Housing Lobby Coalition too often worked at cross-purposes. "We were always checking on each other, making sure another group wasn't doing something that hurt our interests," said Rainey.

The increasingly fragmented approach to housing was starting to hurt everyone. The advocates' frustration drove them to reassess how they did their work. Over the years, housing advocates had frequently talked with legislators in Salem and distributed fact sheets describing their policy goals. These tactics and others, such as maintaining a media list and issuing news releases, had helped these groups win some housing victories at both city and state levels. But efforts to obtain significant regional or statewide policies were failing, and had been faltering for some time. While the advocates were able to push through some small bills that year, they could not prevent the state legislature from removing $6 million from the Housing Trust Fund. Nor were they able to get the life of the Affordable Housing Tax Credit extended. The Real Estate Transfer Fee, the "Holy Grail" in the eyes of some advocates, seemed no more attainable than it had been when the Portland housing advocates first started pursuing the policy more than 13 years before.

Like Michael Anderson and Janet Byrd, Paul Rainey and his allies had hoped to accomplish more during the 2003 state legislature. "That was a frustrating session...overall we saw a reduction in available funds for affordable housing, as we were losing to other politically popular issues," Rainey said. Highlighting how diffuse their advocacy approach had been, he concluded, "We didn't have a strong voice or collaboration." Advocates felt that if affordable housing were to make it onto the legislative agenda the next time around, the housing groups would have to try something new.

Trying a new strategy: Emulating a successful coalition

While housing advocates were experiencing frustrating defeats in Oregon, a powerful housing coalition was at work elsewhere, communicating with a state legislature that routinely allocated millions of dollars for affordable housing on an annual basis. In the state of Washington, the 15-year old Washington Low Income Housing Alliance had advocated early on for the dedication of $100 million per biennium for affordable housing. By 2006 Washington State's biennial spending had grown to $120 million. In 2003, a significant win for this alliance was the enactment of a document recording fee to support affordable housing at the county level. According to Byrd, Anderson, and Rainey, this coalition's success is due to the broad base of political support it has obtained for affordable housing through forging a coalition of constituents that share broad affordable housing goals, such as housing authorities, affordable housing organizations and other nonprofits, and local governments. After the 2003 state legislative session, Byrd and the Oregon state housing authorities began meeting with Washington Low Income Housing Alliance representatives to explore whether Oregon could apply a similar approach.

The advocates regrouped. Janet Byrd, working for Neighborhood Partnership Fund (NFP), focused on developing a coordinated statewide strategy with the state's community development corporations. NFP strengthened ties with Affordable Housing Now!, an alliance formed the year before by the Community Development Network, a tenants' association, and an environmental livability coalition to launch housing policy campaigns on behalf of Portland area residents. NPF continued to collaborate with community development corporations and other partners to support the creation of affordable homes and economic opportunities for low-income Oregonians. The seeds for collaboration were sown.

Trying a new strategy: Media advocacy training

While exploring the model for Oregon, Byrd learned that the Oregon Hunger Relief Task Force had received media training that helped it shape its hunger message around underlying poverty issues and move hunger advocacy efforts forward. Byrd decided to bring similar training to the affordable housing world. She asked Swati Adakar, the task force's trainer, to facilitate a meeting with some of Oregon's housing organizations, which she convened on October 22, 2003. The purpose of the meeting was to help these groups advocate more effectively for increased affordable housing resources. Some organizational members balked at the idea, claiming that they already knew how to do advocacy. But 30 participants appeared at the first meeting, called "Talking about Housing: A Media Working Group." Lawrence Wallack, Dean of the College of Urban and Public Affairs at Portland State University and Berkeley Media Studies Group founding director, was invited to talk at the group's second meeting.

During that meeting, Wallack described the key elements of an effective advocacy strategy, of which media advocacy was a part.1 The advocates learned that they should have a shared understanding of what needs to change articulated in terms of clear policy goals. They should identify political opportunities to advance their desired policy changes, and mobilize resources to capitalize on these opportunities. They needed to identify their allies and opponents. They also needed to frame the issue effectively to communicate their core values and clearly identify who is responsible for the problem and its solution.

After that session, the training participants came to be known as members of the "Media Working Group," which was to meet almost monthly with Wallack for nine months. Lori Dorfman, the director of Berkeley Media Studies Group, conducted an advanced training with Wallack during one of the later sessions. Throughout this period, the group participated in "framing" exercises, learned about "authentic voices" and "social math," gained practice talking with reporters and writing letters to the editor and op-eds, explored policy options, and looked for political opportunities to mobilize for change. "Those nine months were an absolute watershed for us," said Anderson.

Getting the frames and messages right

The idea of talking about issues within larger frames was a revelation for the Media Working Group. "At the end of that first session," said Anderson, "everyone was mesmerized." The group realized that their talk had habitually emphasized providing information. Prompted during the second meeting to define "affordable housing," the group's responses went something like this:

Affordable housing is affordable to people earning less than 80% of the median family income so that they are not spending more than 30% of their income on rent and utilities.

"Wallack told us 'you aren't going to convince anybody about anything if you talk like that,'" Anderson remembers. Beth Kaye of Portland's Bureau of Housing and Community Development added, "It's almost as though we had been talking about tightening a bolt on the rear assembly of a car, which actually might have been more understandable to people."

The group found the discussion about message levels especially helpful. Using a rubric first developed by cognitive linguist George Lakoff, the workshop covered how to differentiate between three levels of messages: (1) the expression of overarching values; (2) the general issue being addressed, such as housing in this case; and (3) the policy details relating to the issue.2 The advocates learned that they had been able to talk about Level 3 policy details, but hadn't been emphasizing their Level 1 values. But if they were to make the case effectively they would need to use all of these message levels to help shape the way people think about housing issues and advance their policy goals.

"It took us three months to define 'affordable housing' with something that wasn't jargonized," said Anderson. "We were so entrenched with statistics and industry terms. We were great at talking at the policy level. But this isn't what was going to change people's hearts; it was too technical. If we continued to talk on this level, we were going to be trumped by our conservative counterparts." After lots of practice, at the end of the third month the Media Working Group had arrived at a definition that focused on Level 1 values of fairness and equity using simple, clear language: "Housing should be affordable enough to be able to pay rent and still put food on the table."

The Media Working Group also learned that they had been spending too much time talking about the problem and not enough time focusing on the solution. "If we had five minutes to talk to people," said Anderson, "we would spend 4.5 minutes talking about how serious the need was. We should have spent just one minute on the need and the rest of the time on why that need is important in terms of values, how it matches what people care about, and what action should occur because of the need." Anderson was articulating another important lesson for advocates. Wallack recommended that they structure their messages to contain three components, clearly conveying (1) what's wrong, (2) why it matters, and (3) what should be done about it, with most of the emphasis placed on the second and third components.1

Focus groups

To develop their core frames and messages, the Media Working Group decided to learn directly from the public what resonated with them relative to affordable housing. The group hired communications firm Conkling Fiskum & McCormick to run focus groups in three Portland metropolitan area counties (Multnomah, Washington, and Clark) in early 2004. Twelve messages were tested in the focus groups, which Kaye and Byrd had narrowed down from approximately 40 generated by the Media Working Group. Each focus group comprised 10 male and female participants from a range of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

The focus group findings were presented to the Media Working Group in March 2004. Statements that focus group participants found persuasive focused on giving adults and children opportunities to succeed and build better lives. Another message that worked well with participants centered on rewarding people for their efforts: "Hardworking people should be able to afford housing and still have money left over for food and basic necessities." The notion that investing in housing is good for the economy because it creates local jobs — a message the advocates had used frequently in prior campaigns — did not work as well. Participants also were less persuaded by the idea of affordable housing as an investment that helps communities save money on healthcare and public safety.

Polling

The focus group messages shaped a poll conducted by Patricia McCaig of McCaig Communications and Opinion Research in the fall of 2004. The specific purposes of the poll were to probe public awareness and general attitudes about affordable housing and its spokespersons; identify affordable housing priorities and key beneficiaries; examine reactions to their key policy goal, the Real Estate Transfer Fee; and further test different messages and messengers. Shortly after its completion, results of the poll, which was funded by the Enterprise Foundation and Living Cities, were presented to the housing advocates. "We found that the door they had been trying to go through...they hadn't even gotten it unlocked and opened," said McCaig.

An important finding was that a large number of respondents believed that low cost or affordable housing was available in their communities, with more than half of the respondents saying that affordable housing was "somewhat" or "very" available. When participants rated the 10 most important issues facing their community, low-cost housing ranked last behind healthcare and education. Despite the fact that the housing organizations had been carefully documenting the tremendous need for affordable housing, the public's perception of the problem did not match the reality. "The compelling need for affordable housing wasn't very stark for the public as compared to other priorities," McCaig concluded. For the advocates, finding this out "was a real jolt."

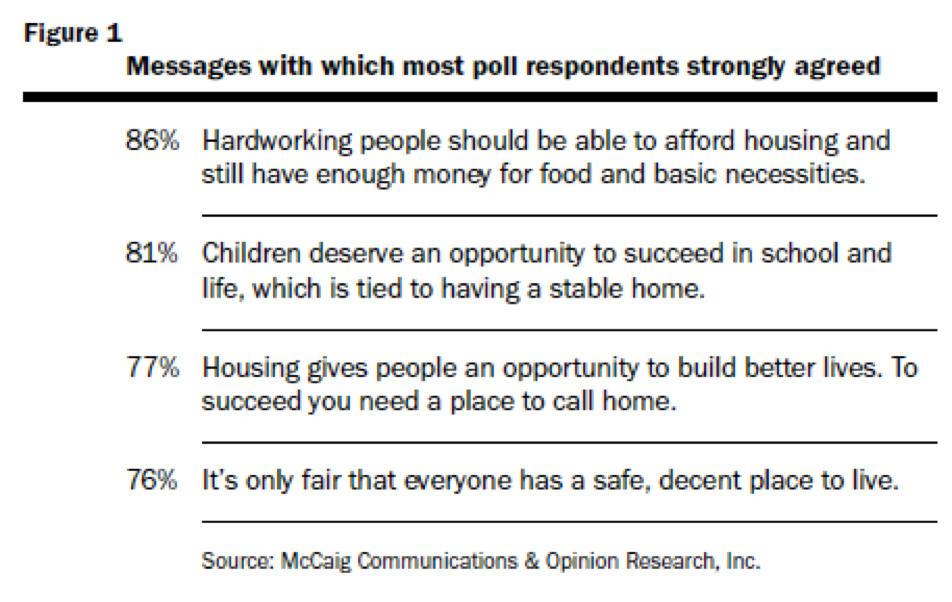

McCaig found that people identified with statements that expressed the values of hard work and reward for effort, children and family, and the opportunity to succeed in life (see Figure 1 above). Some of these evoked the values of personal achievement and individual responsibility, dominant frames in our society. Participants' responses to statements like this seemed to reflect fears that "you could lead productive lives and play by all the rules, but still find yourself not being able to afford housing," said McCaig. There might have been some unease that "this could happen to someone's mother, brother, or child."

Anderson later commented that referring to working people rather than low-income people was an important shift. "If you focus only on poor people," he said, "you help perpetuate the myth that poor people don't work." The research also revealed that the public believes that seniors, people with disabilities and single parents ought to have housing they can afford. As a result of this analysis, the Media Working Group deleted "low income" from its core statements.

These four statements became the flagship messages of the Media Working Group's new media advocacy campaign. In the October 4, 2004, issue of its electronic newsletter, Community Development Network aptly explained the reason: "As housing advocates, we need to constantly remind folks of the 'why' behind the work that we do, and give them a big-picture frame to fit our work into. For example, talking about housing as creating opportunity fits into the bigger frame of America as 'the land of opportunity,' and makes people feel good about the ideas that follow."3

You can't have a media advocacy strategy without an overall strategy

As the polling phase of its work neared completion, core members of the Media Working Group turned more of their attention to developing an overall strategy, which included building new alliances and setting new policy goals and targets (those with the power to implement the policy change). "Media advocacy did not stand alone," said Anderson. "It had to be part of an integrated plan. The messaging does not guide the target. First you identify the target, and bring the messages to them. We had begun to think about this already, but the training helped hammer this home."

Forging a new coalition

Through communications with their Washington neighbors, Byrd and others had come to the conclusion by now that the advocates should build a new statewide coalition patterned after the Washington Low Income Housing Alliance. The media advocacy training confirmed that they were on the right track in this pursuit; framing the issue differently had created a new opportunity to form new partnerships among a wider spectrum of organizations that shared the housing advocates' broad goals.

With the Washington Low Income Housing Alliance serving as a model, core Media Working Group members began reaching out to form a strong and diverse alliance of constituencies to work together on securing significant money for affordable housing. These constituencies were city and county governments, housing authorities, housing providers, and nonprofit partners that shared common concerns about housing, the economy, hunger, health care, land use, poverty, and education. Real estate agencies, mortgage bankers, and home builders, all members of the Housing Lobby Coalition that had been created in the 1990's, were not invited to participate in the new group. According to Paul Rainey, the realtors and bankers were no longer as invested in affordable housing as they had been in the 1990s when the Housing Trust Fund was initially established. Janet Byrd added that the Housing Lobby Coalition was not a real advocacy coalition; they could never agree on an advocacy agenda due to conflicting interests and who was at the table. "There was no proactive voice for housing. Advocates were negotiating against themselves before they even sat down at the table," she said.

Out of this vacuum rose the Housing Alliance, officially founded in April 2004. The key drivers in this coalition's formation were Janet Byrd, Michael Anderson, Lane County Law Center attorney John Van Landingham, Phil Donovan of the Association of Oregon Housing Authorities, and Ellen Lowe, a lobbyist for the Oregon Food Bank. The objectives of the member-funded Housing Alliance are to foster champions for affordable housing among opinion leaders, raise housing as a priority issue in the state legislature, and secure a sustainable source of funding for affordable housing. In the fall of 2005, Anderson and Byrd received an award for their leadership in the formation of this alliance. Every two years, the Community Development Network presents this tribute, called the Gilman Award, to a community development organization for "extraordinary innovation and positive community impact."

Identifying policy goals and targets: The 2005 legislative agenda

The Housing Alliance met regularly over several months in 2004 to discuss the policies they would pursue. Alliance members hammered out common areas of agreement while acknowledging their right to take independent positions on some issues. For example, the Housing Alliance was not able to reach consensus on the issue of prevailing wage regulations for affordable housing. Some members support all efforts to expand living wage jobs, but the housing developers remain concerned that this would further drive up the costs of building affordable housing. Alliance members agreed to a process to keep discussion alive on issues that were points of disagreement, while focusing on policy goals that were acceptable to all partners.

For help with identifying winnable policy victories, the alliance hired Mark Nelson of the Public Affairs Council, a lobbyist with access to both Republicans and Democrats in the state legislature. By October 2004, the coalition had its short list of policy priorities set for the 2005 legislative session. The Housing Alliance was deliberately statewide in its approach. This was a strategic decision designed to help "feed the growth of the coalition," said Anderson. The first state-level policy goal was to increase funding for the Oregon Affordable Housing Tax Credit and extend its "sunset clause." The second was to expand the eligibility criteria for the earned-income tax credit for working, low-income individuals. The alliance chose not to pursue the Real Estate Transfer Fee, acknowledging that they would not obtain adequate Republican or Democratic support for this in the state legislature. "Sometimes you have to separate your policy head from your political head," said Byrd. "It's an elegant solution; a dedicated source of revenue. But politically it's extremely difficult." Instead the alliance remained focused on policy goals it considered winnable within that year's political climate.

Taking the messages to the state legislature

Armed with new policy priorities and messages, Housing Alliance legislative outreach spokespersons descended upon Salem for the 2005 legislative session. These advocates, coordinated by lobbyist Mark Nelson, included a wide range of Housing Alliance organizations: the City of Portland, the Oregon Food Bank, the Lane County Law and Advocacy Center, the Association of Oregon Community Development Organizations, as well as the Association of Oregon Housing Authorities, Janet Byrd's Neighborhood Partnership Fund, and Michael Anderson's Community Development Network.

This time around, the housing advocates found it easier to talk with legislators. "Before," said Rainey, "everyone was pursuing their own agenda." Now they had come with a unified message to share with state legislators. They all used common talking points about what's wrong, why it matters, and what should be done about it. Rainey recalled that in the past, the advocates would explain to lawmakers how affordable housing helps the economy. "We talked too much about the need, about statistics. This time," he said, "we kept the thing value-based. We've made the issue harder to sideline. You can't argue with the values we are promoting." In addition, the legislators were now hearing about the issue in the same way from more people, more often, and from a more diverse group of constituents.

Coordinating communications

While spokespersons were bringing the movement's key messages to lawmakers on the ground in Salem, others worked to infuse the messages in their advocacy materials and propel their newly articulated values and solutions into the news media. Recognizing that the editorial pages are critical for reaching opinion leaders, Community Development Network and Neighborhood Partnership Fund initiated a housing messaging listserv as a conduit for getting housing issues in the newspaper. Beginning in early 2004, more than 40 listserv volunteers began taking turns writing and submitting opinion pieces in response to newspaper stories about housing. One volunteer would post to the listserv a draft letter to the editor or op-ed, others would contribute to editing it, and another would polish and submit the letter to a newspaper. For each of these opinion pieces, writers crafted a lead sentence, used one of the four key messages, and stated the proposed policy solution being advocated for at any given time. CDN also began a "Letter-Writing Brigade," a list of people that housing advocates could call for letter-writing campaigns needing a rapid response. Before the listserv, these advocates had not approached the media in any systematic fashion.

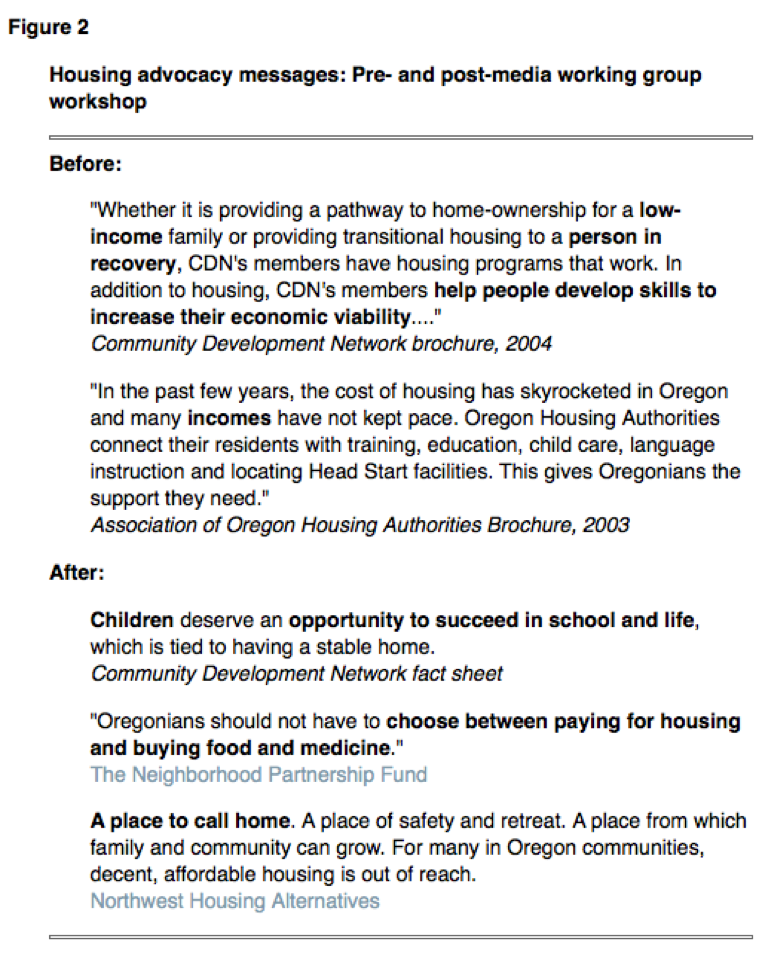

In addition to the letters to the editor, the housing groups also began framing affordable housing differently in websites, brochures, press releases, and other materials. Not all Housing Alliance members consistently changed their materials, but the process of talking differently about housing had begun. Figure 2 illustrates how some Housing Alliance Members talked about their work, both before and after the Media Working Group began to meet.

The earlier materials talk about affordable housing beneficiaries as "low income" people, persons "in recovery," and people who need training, education, and employment. They do not cite specific populations with which most focus group and poll respondents empathized. Expressions like "housing programs that work" also may evoke the idea of "government efficiency," another value that was not highly rated in the polls. Two of the "after" examples focus on children or families, and all of them make explicit the values that the housing advocates hold deeply.

Using these messages in writing is not difficult, claimed Kate Kealy, Communications Coordinator for Northwest Housing Alternatives and member of the housing listserv. "It's a good short-hand; a simple way to engage people in what I'm talking about," she said. "I believe in using these messages all the time to broaden people's understanding of the issue." Kealy began using the messages in every communication she could, from grant applications to tickets for a fundraising event.

New language and standing ovations

While some Media Working Group participants continued to feel more comfortable framing their affordable housing messages in print, the media advocacy training also helped people communicate more effectively about housing when they spoke. Particularly helpful to some participants was the working group session in which Wallack taught participants how to prepare a "safety phrase" going into any interview or discussion about the topic. "You can use it if you feel like you're getting lost in an interview," said Beth Kaye. Kate Kealy added, "It's the brief phrase that gets you back to something like, 'remember, we're talking about giving folks the opportunity to build better lives.'"

Anderson credits the media advocacy training to his improved speaking skills. Invited by a coalition of churches and faith-based communities to give a 25-minute presentation on affordable housing in January 2005, he spent no more than three minutes talking about the need, and dedicated the rest of the time to the solution and the Level 1 message, "everyone needs a place to call home." Recalling from the training that people often learn best from stories, he linked this message to a scriptural passage, tales about his childhood, and the Bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence. He did not utter the words "affordable housing" anywhere in the speech. As he concluded his talk, people were on their feet with applause. This was the first time he had received a standing ovation for any speech.

Media advocacy tools shared with more housing alliance members

The media advocacy training also has revitalized Affordable Housing Now!'s speakers bureau. Before the Media Working Group began, Affordable Housing Now!'s speakers bureau training entailed lengthy briefings on the pressing need for affordable housing and on the complexities of specific policies. According to Anderson, some advocates had felt insecure about their familiarity with the details, making it difficult to recruit volunteers. With the shift to connecting people's values with affordable housing solutions, Anderson said it became easier to recruit, train, and retain speakers bureau participants. From 2004 to the spring of 2006, the speakers bureau membership grew from 11 to more than 25 members.

The speakers bureau training changed significantly after the formation of the Media Working Group (see Figure 3). The "pre" training agenda, which kicks off with "describing the need," contains mostly Level 2 and Level 3 messages (housing, hunger, school success, the economy, affordable housing tools). The "post" agenda begins with "speaking your values," and walks participants through a five-sentence message that articulates the problem, values related to the problem, and solutions.

The nine months of media advocacy training that the advocates had received also served as the basis for new training offerings around the state. In the summer of 2004, Neighborhood Partnership Fund hired Renee Davidson of the public relations firm Grassroots PR to share the new media advocacy tools with more of Oregon's Housing Alliance members. Between July 2004 and spring 2006, Davidson conducted approximately 15 training sessions, targeting executive directors, board members, and other organizational leaders who communicate with the media or policymakers.4

New frames and messages appear in the media

Affordable housing has started to be portrayed differently in newspapers since the group changed its message. Before September 2004, newspapers often cast affordable housing in a negative light, repeating messages found to be ineffective in the focus groups and polls. The old frames focused on efficiency, economy, and housing residents' individual responsibility. The news frames also portrayed affordable housing as bringing problems to communities or benefiting big developers.

Method used to analyze frames in print media

To see whether the advocates' new message was appearing in the local media we mapped and analyzed how affordable housing was discussed in local daily newspapers. Framing analyses like these can help advocates understand the breadth of perspectives around an issue, identify opposing views and potential opponents, and illustrate how advocates' arguments are being portrayed.

For this framing analysis, we used the search term "affordable housing" to examine a sample of articles, editorials, letters to the editor, and op-eds published between October 2004 and March 2005. We searched a database of three of Oregon's largest newspapers: The Oregonian (Portland), the Register-Guard (Eugene), and the Statesman Journal (Salem), and reviewed articles within three nine-month intervals: (1) October 3, 2003 - March 4, 2004 (pre-focus groups); (2) April 4, 2004 - September 31, 2004 (post-focus groups); and (3) October 4, 2004 - March 31, 2005 (post-polling). We reviewed 79 pieces, a random sample (every fifth item appearing in the database) of the 398 articles we collected in the search. We supplemented this review with 30 news clippings supplied by the Community Development Network.

"Before" frame examples:

- The provision of affordable housing and related services is more cost-effective than jail or other options/affordable housing helps the economy. "'As a community, we need to see that a partnership between social/medical services and the housing authority is a more economical solution than hospitalization, jail, or homelessness....'"5 (Statement from chair of the Housing Authority of Portland Board of Commissioners.)

- Affordable housing residents should be more self-sufficient. "'Just as we are asking our residents to be more self-sufficient, we have to be more self-sufficient.'"6 (Statement from chair of the Housing Authority of Portland Board of Commissioners.)

- Combating homelessness (through affordable housing) helps the economy. "'The perception also exists that...homelessness is hurting the local economy,' the plan said."7

- Affordable housing causes public safety and other problems. "Commissioners sided with opponents who said the project — in which most lots would be 3,200 to 4,000 square feet — would create traffic, environmental and public safety problems."8

- People needing affordable housing need skills in order to work. (This could imply that they don't work.) "It also calls for finding ways to incorporate access at cheaper rates for needy people in affordable housing so they can gain access to job training and educational opportunities."9

- There is a pressing need for affordable housing (usually accompanied with technical definition). "'...affordable housing. There is so little of it.' The basic federal standard for most housing programs is that housing shouldn't cost more than 30 percent of a person's income."10 (Statement from a representative of Community Partners for Affordable Housing.)

- Affordable housing benefits big developers. "His argument that the 15-wide food houses meant affordable housing for medium and low-income families cast him in the light of having been bought out by big developers, the neighborhood activists say."11

Some of these frames reflect how advocates said they talked about affordable housing before the media advocacy training, when definitions, cost-effectiveness, and "helping the economy" arguments were part of their regular "talking point" repertoire. News frames focusing on homelessness as a social problem that affordable housing can address also seem to have decreased after September 2004. The number of frames depicting affordable housing as housing that people in general find "affordable to purchase" dropped as well.

After March 2004, frames used strategically by advocates began to appear in the news with greater frequency. Other frames conveying social values that positively portrayed affordable housing also were more prominent.

"After" frame examples:

- Everyone should have a safe, decent place to live. (Opportunity) "Having a stable, safe home is a fundamental building block to reaching success....If children are our future, we need to do a better job investing in their success, and that begins with a safe, stable, home."12 (Written by Dee Walsh, Executive Director, REACH Community Development, Inc.)

- "Home is what gives people the opportunity to build better lives."13 (Written by Michael Anderson, Communications Coordinator, Community Development Network)

- "With stable housing, lives improve." (headline)14 (Written by Maxine Fitzpatrick, Executive Director, Portland Community Reinvestment Initiatives, Inc.)

- "To succeed, we all need a place to call home."15 (Written by Kate Allen, Director, the Enterprise Foundation)

- Reward for effort. "Seniors are faced with the terrifying choice of paying rent or buying medicine with the pensions they worked hard to earn."16 (Written by Janet Byrd, Executive Director, Neighborhood Partnership Fund)

- The provision of affordable housing is a moral or social justice issue; a matter of love and compassion. "Affordable housing becomes even more critical....That is exactly what this is all about, caring and helping people."17 (Statement from Wesley Taylor, pastor of Tualatin United Methodist Church)

- Affordable housing benefits the whole community. "People can improve their lives when they have stable housing. Kids do better in school, neighbors build community and the whole family benefits."18 (Written by Maxine Fitzpatrick, Executive Director, Portland Community Reinvestment Initiatives, Inc.)

This analysis of a small sample of articles published within an 18-month period captures only a fraction of the news housing advocates generated from February 2004 through early spring 2006. During this period, with the help of the new listserv, Housing Alliance members wrote at least 55 letters to the editor and op-eds focusing on the themes of reward for effort, opportunity, and the right to a safe, decent home, 41 of which were published in major newspapers.

Moving from head to heart: People begin to change how they talk about housing

By the spring of 2005, advocates began seeing a change in how others talked about housing, from tenants to members of local service agency staff. According to Kate Kealy, when tenants were asked what housing meant to them at a recent Northwest Housing Alternatives meeting, "all of our messages came out of their mouths." While interviewing agency representatives applying for homeless funds in Multnomah county, Janet Byrd noticed that an applicant "used a message straight out of the polls."

New messages, political support, new funding

After the advent of the Housing Alliance, at least one elected official changed his language concerning affordable housing. According to Anderson, Portland City Commissioner Eric Sten, a longstanding supporter of affordable housing, began using the new housing messages regularly in his speeches. During his city council primary election campaign kickoff rally in 2006, said Anderson, the loudest applause came when he declared, "Hard working people ought to be able to afford rent and still put food on the table." His opponent, state senator Ginny Burdick, also came out in favor of increasing the city's funding for low-income residents' homes.

Other Portland policymakers increased their support for affordable housing in both their talk and their actions. According to Ian Slingerland, Director of the Community Alliance of Tenants, Portland's leaders had generally supported affordable housing over the years. Before 2004, however, housing groups had to expend more effort convincing politicians and government officials that affordable housing is the city's responsibility. Later, he said, "this is a given, and instead the city debates how to balance funding for affordable housing with its other responsibilities." This heightened level of support was evident during the city's 2004 electoral races, when city council candidates Sam Adams and challenger Nick Fish both promoted one of the housing advocates' policy agenda items, an urban renewal set-aside, and mayoral candidate and former police chief Tom Potter championed increases in affordable housing funds.

Every year between 2004 and 2006, council members budgeted millions of city dollars for housing for low-income residents. A total of $11 million was allocated for affordable housing during the 2004-2005 budget cycle, and another $2 million in new funding was dedicated to affordable housing for 2005-2006. Advocates anticipated that in 2006-2007 an additional $6 million would be budgeted for this cause. Before 2004, the city's budget for affordable housing had remained at less than $2 million for nearly a decade. At the state level, both of the Housing Alliance's top 2005 policy goals were met. The Earned Income Tax Credit passed, and Speaker of the Oregon House of Representatives, Karen Minnis helped push through the Oregon Affordable Housing tax credit, increasing funds from $10 million to $20 million, and its "sunset clause" was extended through 2020. What was out of reach in 2003 became policy in 2005.

Pushing ahead

Due to their new alliances and advocacy efforts, by 2006 housing proponents felt that their policy agenda was better positioned to succeed in Salem in 2007. The Housing Alliance had established its legislative priorities almost a year before the beginning of the 2007 legislative session; and, for the first time ever, revenue hearings would be held on affordable housing well in advance of the session. The Housing Alliance's new agenda set forth five specific goals for state lawmakers: (1) dedicate $100 million from one-time and ongoing revenues for affordable housing; (2) remove the state's prohibition on local government's ability to vote on the inclusion of affordable housing with new housing construction; (3) assist residents faced with closure of manufactured home parks; (4) provide alternatives to residents who may be displaced due to condominium conversions; and (5) broaden investment guidelines to generate more Housing Trust Fund dollars. The Real Estate Transfer Fee has been replaced by a Document Recording Fee as the identified source of dedicated revenue. This fee will apply to a wider range of transactions but is a smaller fee on any one transaction. Advocates continued to incorporate their new messages in their materials, including the "backgrounders" or information sheets given to state legislators. The Housing Alliance also expects to launch a more concerted media campaign September through November 2006, involving editorial board visits, and more letters to the editor and op-ed placements.

Despite their many gains, some advocates felt a need for improvement in how the media advocacy tools are used. Some housing group leaders, for example, did not change how they talk about housing due to their lack of comfort with the new language. According to one advocate, "the frames didn't stick with me as well as with the others...I haven't put it into practice myself."

By early 2006, participation in the listserv was beginning to flag, with fewer people creating the primary drafts of opinion pieces. The Media Working Group had recruited only a handful of people as Letter-Writing Brigade members, the list of people that housing advocates were to call for rapid response letter-writing campaigns. Anderson had originally hoped to involve 50-100 people in this effort. He felt that a full-time staff person was needed to handle these time consuming, hands-on media activities.

By the spring of 2006, the housing advocates had come a long way since those frustrating days in Salem three years earlier. As housing costs continued to grow, more challenges lay ahead. But now the groups were working within the framework of a growing alliance. They had an arsenal of media advocacy tools and a trained cadre of individuals actively applying them. Their issue had become more prominent in the news, frequently framed in terms of their short list of core values. And more policy makers were stepping up to allocate more funding for affordable housing in Portland and across the state. Finally, some housing groups will always compete with one another for funds. But instead of fighting amongst themselves over small amounts of money, the coalition members have learned to advocate for larger pots of money from which funds can be allocated. Everything seemed to have changed, including and perhaps most importantly, the very way advocates thought about and framed the issue.

Coda: Policy makers continue to talk about housing and advocates win new victories

As of early June 2006, the Housing Alliance's policy agenda remained on track. On June 1, the House and Senate Interim Revenue Committee held a joint hearing to introduce the Housing Alliance's proposal for the 2007 session for $100 million to be allocated for affordable housing in the 2007 legislative session. Ryan Deckert, the Senate Chair of the interim House Senate Revenue Committee, opened the hearing saying, "Today's hearing is about housing, and it is about opportunity." Earlier, on April 20, 2006, the Portland City Council unanimously passed a resolution to create an urban renewal set-aside. This set-aside, which guarantees that a percentage of funds will be allocated for affordable housing as part of any urban renewal project undertaken in the city of Portland, has been one of Affordable Housing Now!'s central policy targets since 2002. Housing proponents are advocating that 30% of urban renewal funds be set-aside for this purpose. The resolution directs city agencies to work with Affordable Housing Now! and other stakeholders to submit a set-aside implementation plan to the city council by September 1, 2006. Previously "this was considered an almost impossible victory," Anderson said.19 According to Anderson, the speakers bureau played a pivotal role in getting the urban renewal set-aside on the city's policy agenda in 2006. Prior to the passage of this resolution, Affordable Housing Now!had strategically dispatched 15 speakers to four city budget hearings convened by the mayor over a four-month period. Eight speakers appeared at the first of these forums. Since school issues were often voiced as concerns at these meetings, the speakers most frequently used the message, "children need an opportunity to succeed in school and life." As the mike moved around the room in "Phil Donahue" style at these hearings, others in the crowd would repeat parts of this message. In the end, said Anderson, the speakers "forced a discussion of urban renewal through the budget process." Not only was the issue placed on the policy agenda for discussion, but it has now been passed into law.

Lessons learned

- Level 1 messages done right accommodate different Level 3 policies.The range and type of housing policies pursued at both city and state levels shifted over time between 2003 and 2006. Advocates sought after some of these consistently throughout this period, such strengthening the Oregon Affordable Housing Tax Credit and establishing an urban renewal set aside for the city of Portland. Other goals changed, either in terms of the policy to pursue, the policy component to emphasize, or the policy's level of priority. Preserving the Housing Trust Fund in 2003 became less of a priority in 2005. The 2005 policy agenda included increasing the eligibility criteria for the earned income tax credit, a goal that had not been pursued in 2003. Those initially advocating for the Real Estate Transfer Fee in 2003 abandoned this pursuit in 2005 in favor of lobbying for statewide policy initiatives. As the advocates learned, policy goals are communicated in Level 3 messages. Some of these Level 3 policies changed over time, but the advocates consistently remained grounded in Level 1 values such as fairness, reward for effort, and the opportunity to succeed in life. The advocates had successfully made the transition from talking about Level 3 to talking about Level 1 in their public communications and policy advocacy. Moving forward, these values frames would remain a foundation accommodating a range of various Level 3 policy goals.

- Media advocacy strategies must be embedded in a larger advocacy strategy.The success of the advocates' media advocacy strategies was contingent upon having the right partners in place and selecting the right policies to pursue. Their media efforts were embedded in a larger advocacy strategy, which included learning from the successes of others, coalition building, and crafting strategic, unified policy agendas. Early on, the advocates reached out to the Washington Low Income Housing Alliance to learn what strategies they had used to build a broad base of political support for affordable housing. The Housing Alliance subsequently created in Oregon was patterned after this coalition. Key to the success of this newly formed coalition of diverse constituents was its ability to set aside differing priorities to focus on a small number of winnable policy targets to which all parties could agree. It was the people in these partnerships who sought to frame their issue in a unified manner in the media, for the public, and with policy makers. And it was these partners who motivated others to join their cause in the process. This approach brought the coalition new gains in the 2005 state legislature, held further promise for the 2007 legislative session, and gave new housing victories to the city of Portland. The tools they used — including the letter writing campaigns, the speakers' bureau, and the modified print communications — helped them get there.

- Even seasoned advocates can benefit from training and reexamining basic assumptions.Before the first media advocacy training session, some affordable housing advocates did not believe they needed more training. Thinking it would be yet another training session on how to talk with legislators and give testimony, some asked, according to Anderson, "why should we show up for this template thing? We know how to do that." Indeed, the affordable housing advocates knew their issue forwards and backwards. They were experts at providing information and statistics supporting their proposed policies. The media advocacy training was more than just another training session — it was an experience that challenged the advocates' assumptions that solely providing information would motivate policy makers to address the problem of affordable housing. Instead the training focused on the importance of appealing to core values in advocating for change. The training made explicit that the advocates' motivation to do this work was grounded in their own set of deeply held values. Framing their issue in terms of these and other widely held values could move policy makers and others to take up their cause. The provision of detailed information about the problem and its solution is necessary to all advocacy work, but the advocates gained skills so they could consistently ground this information in succinct, clear messages conveying the values of fairness, reward for effort, and opportunity.

- Success breeds success.One success led to another as the advocates applied their overall campaign strategy and used their media advocacy tools. Framing their issue within core values made it easier to recruit speakers bureau participants and writers of opinion pieces for the media. It simplified the task of developing public communications materials, and facilitated the advocates' lobbying efforts among politicians in Portland and Salem. Forging the coalition built political clout and widened the circle of people who could communicate key housing messages and policy goals. Policies that were unattainable in 2003 were won in 2005. Having a coalition in place enabled advocates to set their 2007 advocacy agenda earlier than ever before, and the 2005 successes in Salem informed the coalition about politically viable goals to aim for in 2007. All of these efforts have helped raise the profile of affordable housing in Oregon. "There was no lightning bolt," said Byrd. "People didn't immediately start talking differently about the issue. But people have a stronger commitment to it now. Our newspaper has spent a lot of ink time and space on it. We can't take full credit for this; some of it is the market and economic pressures. But some of it is our media work, our coalition-building work....the messaging helps us motivate people. We're out there pushing, and we now have more opportunities to talk about our issue."

Terms and definitions

The Oregon Hunger Relief Task Force is a quasi-governmental organization comprising nonprofit organizations, state agencies, and the stage legislature. The Oregon Legislature created this task force in 1989 to advocate for programs and policies to eliminate hunger statewide. In the early 2000's, task force members participated in a series of media advocacy training sessions in which they adopted "family economic stability" as a prevailing frame for the hunger issue. Task force members used talking points that emerged from this frame in meetings with governor's office representatives, and later the governor made hunger a priority issue during his first term. The updated version of the task force's five-year strategic plan begins by stating that families are at risk of hunger when shelter and other basic needs are not met.

The Oregon Food Bank (OFB) is a member of the Oregon Hunger Relief Task force. This food bank runs a statewide network of 894 hunger-relief agencies serving Oregon and Clark County in Washington. As a member of the Housing Alliance, the Oregon Food Bank is a significant and well-respected ally of affordable housing. Reputed as an efficient, effective, and financially responsible organization, the OFB was selected in 2005 as Oregon's most admired nonprofit. In a poll conducted between August and September 2004 on behalf of affordable housing advocates, the Oregon Food Bank ranked more highly than other nonprofits, neighborhood associations, law enforcement personnel, small businesses, educators, and religious leaders as a "very believable" affordable housing messenger.

Media advocacy is the strategic use of mass media to support community organizing to advance a social or public policy initiative. A media advocacy plan is the set of strategies and tactics used to attract journalists' attention and frame an issue or proposed policy in the news.

Framing is about how people derive meaning from the world around them. Linguists talk about frames as structures residing in our brain, like ready-made storylines, that let us "fill in the blanks" so cues in the world around us make sense. An easy frame to cue in American culture is Rugged Individualism the idea that if you work hard you can succeed (or, the reverse, that if you fail it's your own fault). Media scholars talk about the specific ways that language and images in news stories shape the way people think about an issue. Every news frame suggests, even if it doesn't state outright, what the problem is and who is responsible for causing it and fixing it. As early as 1922, Walter Lippmann talked about how the news triggered the "pictures in our heads" so that we could tell ourselves a story about whatever was happening those pictures in our heads are the frames we come with that get shaped and reshaped by our direct experience and what we experience through the media.

Authentic voices are people with direct experience who bring that experience to their advocacy. Authentic voices can tell their story and express a desire for change from a personal perspective and attach the details of their lives to a policy solution. For example, members of Mothers Against Drunk Driving are authentic voices because they have lost loved ones in alcohol-related crashes. Persons who must rely on affordable housing to make ends meet are effective authentic voices for this issue. Mary Latourette, an authentic voice, was featured in a May, 2005, Daily Journal of Commerce article about federal housing cutbacks. This affordable housing resident, who relies on a monthly disability check for her expenses, was quoted as saying, "At the end of the month, I have to choose between food and medication."

Social math is the practice of making large numbers comprehensible and compelling by placing them in a social context that provides meaning. To do this, advocates break down numbers by time or place, or compare numbers with familiar things. One example: "There will be 2,200 homeless children in Portland this school year. That many children would fill 80 school buses. Placed end to end, that's enough buses to ring the entire downtown area."

Safety phrase is a transition phrase that allows advocates to return to a key message they want to convey in an interview. This phrase can be used if advocates lose their train of thought or if they are asked a question that could derail them from communicating their main points within the interview's short time frame. Examples include, "remember, we're talking about giving folks the opportunity to build better lives" or "it's important to keep in mind that we're talking about giving children the opportunity to succeed in school." The safety phrase makes sense no matter what comment or question precedes it.

Issue 16 was written by Robin Dean, MPH, and edited by Lori Dorfman, DrPH. Special thanks to all those who were interviewed for this case study, especially Michael Anderson, Janet Byrd and Paul Rainey.

Issue 16 was supported in part by the Communications Consortium Media Center's Media Evaluation Project. For other media evaluation publications see www.mediaevaluationproject.org.

Issue is edited by Lori Dorfman.

© 2006 Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute

References

1 Wallack L, Woodruff K, Dorfman L, and Diaz, I. News for a Change: An advocates' guide to working with the media, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1999.

2 Dorfman L, Wallack L, Woodruff K. (2005) More than a Message: Framing Public Health Advocacy to Change Corporate Practices. Health Education and Behavior, Vol. 32 (3): 320-336.

3 Advocates Learn to Talk about Housing: Putting Values in the Forefront. CDN Electronic Newsletter October 4, 2004.

4 Davidson, Renee. Talking about Affordable Housing. PowerPoint presentation.

5 Angie Chuang. Housing chairwoman sees evolution ahead. The Oregonian. Section: Portland Zoner. January 30, 2004.

6 Ibid.

7 Henry Stern. Portland tries new homeless plan. The Oregonian. Section: Local stories. December 20, 2004.

8 Steve Mayes. Canby turns down 128-Lot Subdivision, urges creativity. The Oregonian. Section: South Zoner Southwest Zoner Lake Oswego Southwest Zoner Tigard; Yamhill. October 13, 2003.

9 David Austin and Wade Nkrumah. Other Action. Section: Portland Zoner. The Oregonian, Nov 6, 2003.

10 Nika Carlson. Authors hope to turn page on housing. The Oregonian. Section: Southwest Zoner Tigard Yamhill. April 15, 2004.

11 Amy Hsuan. City candidates band together, hoping to fracture the field and defeat Leonard. The Oregonian. Section: local stories. April 27, 2004.

12 Dee Walsh. Safe, stable homes for everyone. May 17, 2004. The Oregonian. Section: Editorial. May 17, 2004.

13 Michael Anderson. Expand subsidized housing. The Oregonian. Section: Editorial. August 3, 2004.

14 Maxine Fitzpatrick. With stable housing, lives improve. The Oregonian. section: Editorial. January 27, 2005.

15 Kate Allen. Letters — Portland Zoner. The Oregonian. February 7, 2005.

16 Janet Byrd. Make Housing a Top Priority. The Oregonian. Section: Editorial. February 14, 2004.

17 Wesley D. Taylor. Religion today people work together to open food pantry. The Oregonian. Section: Editorial. October 7, 2004.

18 Commissioner Erik Sten Homepage. "Commissioner Erik Sten puts schools, healthy neighborhoods, and affordable housing on center stage," 4/20/06.

19 CDN Electronic Newsletter April 27, 2006. "Council Unanimously Passes Sten-Adams Urban Renewal Set-Aside Resolution."