Issue 17: Debates from four states over selling soda in schools

Saturday, November 01, 2008Teens are drinking more soda than ever before. In 1996, the average teenage boy in the United States consumed more than 1.5 cans of soda a day, and the average teenage girl drank one 12ounce can of soda per day, over double the amount teenagers drank in 1977.1 Concerned about the health effects of consuming sugary beverages,2, 3, 4 public health advocates around the country are working to create environments where healthier beverages are the norm. Many have focused their attention on schools, where students spend many hours each day, and where adults can control which beverages are sold.

In early 2006, four states, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Maryland, introduced legislation that included restrictions on the sales of sodas and other sugar-sweetened beverages in schools. Within months, the bills had met different fates: two were enacted, a third was rewritten to no longer limit beverage sales, and the fate of the fourth remained uncertain until the close of the year, when it died.

2006 was also the year that the Alliance for a Healthier Generation, a partnership between the American Heart Association and the William J. Clinton Foundation, announced two agreements. On May 3, 2006, a Memorandum of Understanding was established between the Alliance and Cadbury Schweppes, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and the American Beverage Association to change the guidelines for beverages offered in schools5; on October 6, a similar agreement was garnered with Campbell Soup Company, Dannon, Kraft Foods, Mars, and PepsiCo to create voluntary guidelines for snacks sold in schools.6

Soda and junk food were getting attention from the public and private sectors in 2006. We wanted to know: how were the arguments for and against restricting access to soda and junk food being portrayed? Who was making the arguments, and what were they saying?

What we did

This study examines the debates surrounding the 2006 state legislation in Connecticut, Maryland, Indiana, and Massachusetts as reflected in the news and opinion coverage in each state's newspapers and in arguments that appeared in legislative documents. We also examined articles on school nutrition policies from Ohio newspapers in order to compare the public conversation on school nutrition in a state without pending legislation.

For each state with pending school nutrition legislation, we searched newspapers in the Nexis database for relevant articles spanning the date of the bill's introduction through one month after its final status was determined, or the end of the calendar year. The date ranges for Connecticut were February 1—June 30, 2006; for Indiana, January 1—April 30, 2006; for Massachusetts, January 1—December 31, 2006; and Maryland was January 1—May 31, 2006. For Ohio, we searched all of 2006 for articles discussing school nutrition policy.

We assessed two distinct sets of newspaper news and opinion pieces. The first set — Topics in School Nutrition Policy — includes news and opinion pieces from Massachusetts and Ohio. We compared nutrition topics in coverage from these two states since the sample period for each spanned the entire 2006 calendar year. This way, we could compare the general topics in nutrition news and opinion coverage from one state with pending legislation (Massachusetts) and one without (Ohio). The Massachusetts articles that focused on state-level nutrition were not part of this analysis set.

The second set we assessed — State Legislation on Nutrition — includes articles from each of the four states with pending legislation on nutrition. In this set we examined the frames, or central arguments, that characterized the debate. Frames are powerful because they foster certain interpretations and hinder others — often without the news consumer's awareness. Frames shape the parameters of debate as they create tracks for a train of thought and once on that track it's hard to get off.

To determine how the pieces were framed we read a small number of stories to generate preliminary categories, using as a starting point the coding instrument we developed for our prior study of the first school soda sales bans in California (see Issue 157). After reading the sample, we revised and added to these frames, coded another sample, discussed our findings, and further revised the coding scheme to reflect the frames we were seeing in the coverage, resolve differences, and refine our categories. We repeated the process until we were satisfied that the frames included in the analysis reflected the full range present in the sample. Because the local context was quite different across states, refining the frames was more complex than it had been in our California study where the policy context was quite similar across study sites.

We also analyzed legislative documents for frames. We found these documents by collecting available materials from the states' government Web sites, the University of California, Berkeley law school library, and from relevant offices in the particular states, such as the offices of bill sponsors and committees. In one case (Maryland), we ordered copies of testimony and a CD of a public hearing. The documents available by state varied widely; depending on the state they included proceedings, fiscal analyses, testimony, votes, committee reports and hearings, letters, bill histories, and digests or synopses of the bill.

State legislation overviews

Connecticut passes a school nutrition bill by legislative substitution

Senate Bill 373, "An Act Concerning Technical High School Wiring for Technology," was introduced on February 23, 2006, when it was referred to the Joint Committee on Education. The bill would have established a competitive grant program for Connecticut schools to receive money for technology wiring, such as electrical and cable wiring.

Senate Bill 381, "An Act Concerning Healthy Food and Beverages in Schools" was introduced the same day and sent to the same committee. This bill limited which beverages could be sold in Connecticut schools and gave the Department of Education the task of publishing annual nutrition standards for foods sold at schools outside the National School Lunch and Breakfast Programs.

On March 31, 2006, SB381 failed in the Joint Appropriations Committee, but on April 3, 2006, the language of SB381 was substituted into SB373 in the Joint Finance, Revenue, and Bonding Committee, at which point SB373 became "An Act Concerning Technical High School Wiring for Technology and Healthy Food and Beverages in Schools." After two more iterations under the same name, it became SB373, "An Act Concerning Healthy Food and Beverages in Schools." The language for technical wiring was taken out of this final bill. On May 19, 2006, it was signed by Governor M. Jodi Rell, and became Public Act Number 06-63, effective July 1, 2006.

Indiana limits sweetened beverages in schools

Senate Bill 111, "An Act to Amend the Indiana Code Concerning Education", was introduced on January 9, 2006 and referred to the Committee on Health and Provider Services. Among its provisions, the bill set nutrition standards for schools by establishing "better choice" foods and beverages and requiring at least half of foods and beverages offered at school to fall into this category. It passed the Senate on January 19, 2006 and the House on February 28, 2006 with minor amendments. The Senate concurred with the House amendments, and passed it on March 6, 2006. It was signed by Governor Mitch Daniels on March 15 and became effective on July 1, 2006, and is known as Public Law 54.

Maryland guts its bills and then enacts none

In 2006, Maryland had concurrent bills with the same goals of 1) adding body mass index (BMI) and diabetes screenings to the scoliosis screening tests performed on public school students, and 2) setting nutrition standards for foods sold in public schools. House Bill 1418 was first read in the Ways and Means Committee on February 10, 2006, Senate Bill 457 was first read in the Committee of Education, Health and Environmental Affairs on February 2, 2006.

One of SB 457's co-sponsors sponsored another bill regarding school nutrition, SB436, which aimed to establish a Maryland Obesity Awareness and Prevention Task Force. This bill died in the Education, Health and Environmental Affairs Committee on March 27, 2006. However, the House Ways and Means Committee amended HB1418 to look like SB436, and changed the name of the task force to the Maryland Obesity Awareness and Prevention Blue Ribbon Panel. The Senate Education, Health and Environmental Affairs Committee did the same with SB457, naming the task force the Maryland Healthy Student Promotion and Awareness Blue Ribbon Panel. Little of the original language was kept for either bill. The new versions of HB1418 and SB457 set rules for the panels, the general goals of which were to make recommendations to promote physical activity and increase awareness of obesity and prevention among school-age children.

Though both bills passed in their respective chambers (HB1418 on April 7, 2006 and SB457 on April 8, 2006) neither was signed by Governor Robert L. Ehrlich, and were not enacted.

Massachusetts' nutrition bill dies

Senate 2373, presented by Senator Richard T. Moore, was submitted on February 14, 2006, as a partial substitution for House 3637. Titled "An Act Promoting School Nutrition," S2373 set school nutrition standards, established a commission to conduct an analysis of childhood obesity, nutrition, physical activity, and education and wellness within the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and set standards to train school personnel about treatment, identification, and resources for students with eating disorders. The bill remained in the Senate; it was postponed eight times before the legislative session expired at the end of 2006, when the bill effectively died.

What we found

Topics in school nutrition policy: Ohio and Massachusetts

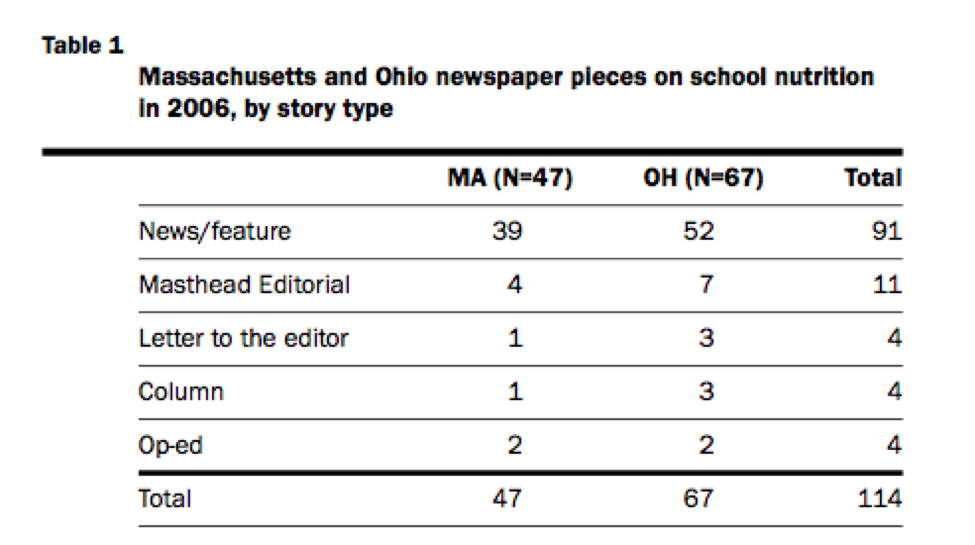

Stories about general school nutrition policy appeared throughout 2006 in both Massachusetts — a state with pending legislation — and in Ohio — a state without pending legislation. Overall, we found 77 news and opinion pieces for Massachusetts and 67 for Ohio. Of Massachusetts' 77 articles, 30 focused on statewide legislation. Those articles constitute the most frequent topic for the state. It is reasonable to expect that when legislation is being considered, that topic will dominate news coverage. We examine the frames in those 30 articles in the next section with coverage from the other three states that entertained statewide legislation on soda. In this section we analyze the topics of Massachusetts' remaining 47 articles with Ohio's 67 articles. The majority (80%) of pieces were news or feature articles (see Table 1). The remaining pieces were from the opinion pages.

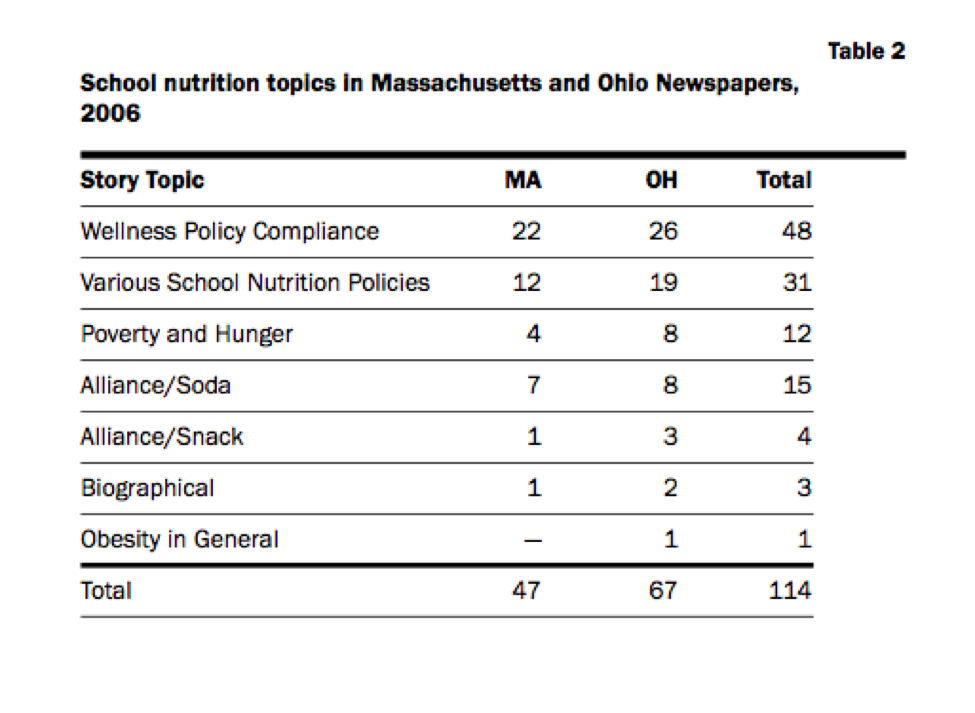

The most prominent school nutrition topic concerned schools' compliance with a new federal law requiring school wellness policies (see Table 2 below). The Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 required that each school district in the country create a wellness policy that set nutrition standards and goals for nutrition education and physical activity by the beginning of the 2006-07 school year.8 Forty-two percent of the articles covered some aspect of a school district's work on a wellness policy.

Thirty-one pieces reported on a mix of school nutrition policy issues in the two states that were not about wellness policy compliance. This reporting covered school district policies to change lunch offerings to increase revenue, assessments of the percent of districts that offer healthy food choices for students, and, in an editorial, entreaties to the gubernatorial candidates in Ohio to support school nutrition.

Twelve articles addressed school nutrition as it related to poverty and hunger. These stories linked poor childhood health to poor nutrition, obesity, and/or poor academic performance. In ten of 12 cases, the articles mentioned expanding school breakfast programs.

In May 2006, the Alliance for a Healthier Generation, in conjunction with several soda companies, announced an agreement to change beverage offerings in schools. Massachusetts had seven pieces focused on the Alliance's beverage plan, while Ohio had eight. In October of that year, the Alliance announced an agreement with several snack food companies to change the selection of foods they offered in the nation's schools.9The announcement about the Alliance's snack food agreement garnered about one-quarter of the attention as its soda announcement had; Ohio had three articles on this topic and Massachusetts had only one.

Three pieces were biographical, highlighting individuals, including one school district's new "food chief" and two other districts' food service directors. The features reported on each person's contribution to the school's nutrition policy and the fight against obesity. One Ohio article focused on the problem of childhood obesity in general and possible solutions.

State legislation on school nutrition: Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Maryland

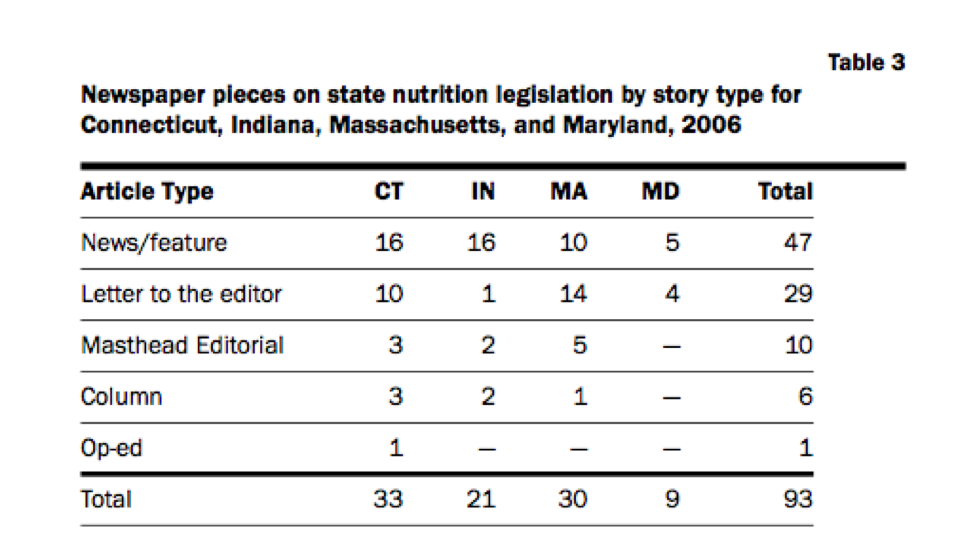

Across the four states that had state-level legislation in 2006, we found 93 news and opinion pieces that covered state legislation on school nutrition (see Table 3 below); a little over half (51%) were news or feature articles.

These pieces all focused on the pending legislation in each state. A subset of the debate (three news pieces, four opinion) in Massachusetts drew heated attention from many parties over a proposal to outlaw Fluff, a sugar and marshmallow spread that is used in school lunches with peanut butter to make sandwiches.

State legislation on school nutrition: Frames in the news and opinion coverage

We analyzed the 93 articles covering state legislation on nutrition for frames, or arguments made during the debate.10The most frequently appearing frame was obesity threatens health, which appeared 35 times in the sample, including six times when it was evoked by elected officials. This was the most frequently expressed frame by this group of speakers. Frames used to oppose the respective state's proposed legislation appeared 39 times, less often than the supporting frames, which appeared 57 times.

Frames supporting state legislation on school nutrition

Obesity threatens health captures the concerns over the detrimental effects of obesity on health, as well as the concern over the recent rapid rise in obesity rates among children and adults in the United States. As one letter writer from Massachusetts put it, "Childhood obesity has grown dangerously high in our state and our country. If we don't do something about it, today's generation will have a lower life expectancy than their parents."11 As part of this frame, the risks of diabetes and other ailments are also expressed, as is the reason schools are changing nutrition policies — to fight obesity. Obesity threatens health was almost always used as a justification for policies that restrict children's school access to junk food or soda; it was the most prominent frame supporting the proposed changes in nutrition policy in the four states.

Another frame favoring restricted access to sodas in schools was school responsibility, which argues that schools are responsible for children's well being, including their health, and so exposing students to harmful products on campus, such as soda and junk food, is shirking the school's responsibility. As one senator from Connecticut said, "There is no parent that I know who wants their child to consume unhealthy food or beverages. When we are caring for that child, it is up to us to step into the role of parent and do what every parent wants for that child."12 The school responsibility frame implies in loco parentis, the responsibility of a person or institution to assume some duties of a parent. This frame appeared five times, including three times from elected officials.

Invoked four times, soda has no nutritional value, argues that it is appropriate to ban soda because, as a Connecticut Post editorial put it, soda is "largely nutritionally worthless"13 and not needed for daily activity. Four speakers argued that better nutrition leads to better learning, which equates good health with good academic performance. According to one Maryland senator, "You can't be a good learner if you've got a bad diet."14

Other frames that appeared fewer than four times included practice what we preach, which asserts that schools need to lead by example and not send mixed messages by teaching children in the classroom to eat well and then offering fast food and soda for lunch. Some speakers defended the policy proposals by insisting kids will buy healthier alternatives if given the opportunity. As one senator from Indiana stated, "I think if we give kids healthier choices, they'll make better choices."15 This frame, appearing three times, runs counter to the idea that kids will only eat food that is bad for them. Finally, three speakers believed schools undermine parents, criticizing schools for offering sodas and junk food after parents have tried to support healthy eating and nutrition in the home.

Frames opposing state legislation on school nutrition

Frames used in opposition to state-level school nutrition polices in these four states included the claim that schools need the money from soda and junk food companies because they are struggling to fund activities. This frame argues that without the revenue from the sales of soda or junk food, schools would have to make cutbacks in extracurricular programs. This frame was the only one attributed to school superintendents and administrators, and appeared nine times.

Nine speakers argued that kids will get soda and junk food elsewhere if not in schools, so according to these speakers, the proposed law will have little effect. As one Indiana newspaper reported, "Westfield junior Shawn Snyder, 17, said officials could load the machines with only dried fruit and granola bars and students would still get their junk-food fix at convenience stores or gas stations. 'We pretty much go to Speedway every day, anyway,' he said."16 Implicit in this frame is that kids want junk food, and trying to change them is simply naïve.

The nanny state frame, a familiar argument in many public health policy debates, criticizes the state for interfering with personal choice. As one letter writer put it, "But turning the state into a nanny teaches [students] nothing except that personal responsibility means nothing in our society anymore, and that the answer to any social ill is a new law."17 Nanny state appeared six times. Several opposition frames appeared four times each in the coverage. One frame, offer more nutritional choices, acknowledges that obesity is a problem and schools have a role to play, but disagrees with the strategy of banning soda sales. Instead, the proponents of this frame maintain that schools should expand the choices available. Another opposition frame emphasizes that to combat obesity kids need to be active.

The following opposition frames appeared fewer than four times: parents, not schools, have responsibility for nutrition, which moves the argument from schools to the home, emphasizing personal freedom; sodas and junk foods are part of childhood, which describes the social value in giving kids treats and letting them have fun; and implementation is hard, which emphasizes the logistical difficulties schools might face trying to enforce new policies when they are already struggling to provide educational basics.

News and opinion frame distribution by state

In Connecticut, Indiana and Massachusetts, the most prominent frame in the news and opinion coverage was obesity threatens health. After this frame, other frames were distributed relatively evenly among the states with minor variations. Maryland's most prominent frame was schools need to offer better nutritional choices. Connecticut had four appearances each of nanny state and soda has no nutritional value, while these frames were not prominent in other states. Connecticut and Indiana each had four appearances of schools need funding, which accounted for almost all appearances of this frame. With the exception of obesity threatens health, no other frame appeared more than four times for any state (Table 4).

Framing state legislation on school nutrition in legislative documents

In addition to news and opinion coverage, we analyzed the legislative materials available for the bills related to school nutrition policy introduced in 2006 in Massachusetts, Indiana, Connecticut, and Maryland.

Connecticut and Indiana both had more than 50 documents available, while Maryland had 67 available between its two bills. Massachusetts had very little information, with only five documents. Each state had at least one bill history and one final text of the bill (Table 5).

The majority of these documents did not contain frames as they were procedural, noting the progress of the bills through each state's legislature. Two documents from Connecticut, the House and Senate debates, contained transcripts of the discussion regarding SB373, which revealed clear positions and arguments. Similarly, 26 documents from Maryland, including testimonies by governmental and non-government sources, committee reports, letters, and other documents contained arguments that supported or opposed the legislation. Our analysis focuses on the frames in documents from Connecticut (N=2) and Maryland (N=26).

Of the 14 testimonies from non-government sources, 10 originated from the food and beverage industries, or lobbyists for industry, including the Grocery Manufacturers Association, the National Confectioners Association, the Maryland, Delaware, District of Columbia Beverage Association, and K Consulting, which used one of the same spokespeople as the Grocery Manufacturers Association. The other four testimonies originated from health organizations, including the American Cancer Society, the American Heart Association, and the American Academy of Pediatrics. Five additional documents originated from legislative committees, two came from the State Department of Education, and two came from the Department of Legislative Services. Letters to committees and senators originated from industry (2) or health associations (1). Finally, the House and Senate debates from Connecticut came from the House and Senate floors, and the group of speakers was thus composed solely of legislators.

Frames on school nutrition in legislative documents

As in news coverage, the most frequently appearing frame in the legislative documents was obesity threatens health, which emphasizes the health effects and rapid rise of obesity (Table 6). Better nutrition leads to better learning, a frame linking good nutrition with school achievement appeared nine times. Eight of the nine appearances of this frame were in legislative documents from Maryland. The same frame appeared only once in Maryland news coverage. Parents, not schools, have responsibility for nutrition, a frame placing the responsibility for children's nutrition in the home, appeared six times in Connecticut's documents.

This frame did not appear in the news or opinion articles from Connecticut. Other frames in the legislative documents included kids need to be active (4), which emphasizes physical activity as an important solution to the obesity epidemic; soda has no nutritional value (3), which claims sodas are appropriate to ban due to their lack of nutrients and high sugar content; practice what we preach (3), which calls on schools to be consistent, teaching children good health in the classroom and following up by not offering junk food and sodas for lunch; kids will get soda and junk food somewhere else (3), which argues that the policy change is useless, as children will continue to drink soda that they obtain away from school; nanny state (2), which criticizes the state for interfering with personal choice; school responsibility (1), which argues that schools are responsible for children's well-being, including their nutritional health; and schools need to offer better nutritional choices (1), which agrees that obesity is a problem but emphasizes healthier choices as the solution (Table 6.) Similar to the news coverage, there were more expressions of frames in favor of the respective state's legislation (38) than frames opposing (16).

Conclusion

Policy debate about nutrition leads to news coverage about nutrition policy. In 2006, news coverage about nutrition appeared in response to federal mandates for school wellness plans or in response to state legislation about school nutrition.

Local, state, and federal policy drives news coverage

In our small sample, the nutrition policy topics in Massachusetts and Ohio remained fairly consistent. Absent Massachusetts' news coverage of pending legislation, the general topics discussed in relation to school nutrition were very similar between the two states. In particular, wellness policies and other school nutrition policies were prominently featured. Actions by national organizations with high profile spokespeople also attracted coverage. The distribution of story types between news and opinion were virtually identical for both states. In this instance, the presence or absence of legislation did not seem to affect the news coverage of other school nutrition topics, which was dominated by federal policy mandates and actions at the school district level.

Nutrition policy frames: Obesity threatens health

In the four states under study that considered state legislation on school nutrition in 2006, obesity threatens health was the most frequent frame in news and opinion coverage and in legislative documents. At odds with this support for school nutrition policies was the argument that schools need funding, the next most prominent frame found in the news coverage. We found this same tension in our study of news coverage of the first ban on soda sales in schools (see Issue 15). Until schools are given sufficient resources to carry out their mandate, we expect school officials to continue to seek resources from many places, including soda companies, while others argue it is inappropriate to sell sodas and other sugary beverages in schools.

The relative consistency of frames across states demonstrates that although bills and policies may be different in different places, arguments remain consistent. Based on this analysis, we expect that advocates would encounter similar arguments when they propose policies such as banning the sale of sodas in schools, regardless of their geographic locations.

Though our legislative dataset was limited primarily to Maryland and Connecticut, we learned that the frames depicted in the legislative materials were different than the frames appearing in the news and opinion coverage, though obesity threatens health was still the most prominent. Other frames featured prominently in the legislative documents but not the news coverage included better nutrition leads to better learning, which linked school achievement with good nutrition, and parents have responsibility for their children's nutrition, a frame that puts children's nutrition squarely on parents', not schools', shoulders.

Creating healthy nutrition environments is never easy; it takes proactive policies to change existing environments into healthful ones. As this story continues to unfold, public health advocates and journalists both have a role to play in helping the public and policymakers understand what is at stake and, together, what we, as a society, should do about it.

Recommendations for public health advocates

It is extremely important for advocates of nutrition policy to take a position and make it public. Advocates should issue statements to the media so reporters know when their organizations support or oppose pending legislation, and what the legislation means for the public's health. Despite the recent attention to obesity, the connections between policy and health outcomes need to be explained in the context of specific policy proposals. There are several ways advocates can take a position and make it public:

- Use the opinion pages.

We found only five op-eds out of the 207 news and opinion pieces we analyzed. Yet opinion pages, including letters to the editor, are highly read, especially by elected officials and their staff. Public health advocates can use the opinion pages of newspapers to educate legislators and the public about the advantages of nutrition policy. - Submit legislative testimony.

Most of the testimony we found came from food and beverage industry sources. Advocates are missing an important opportunity to speak to legislators directly by submitting testimony on their research and experience with school nutrition policies. Advocates should learn the practices in their legislatures for making their views about legislation part of the public record. - Reuse news and testimony.

Advocates should share the fact that they have submitted testimony or comments on legislation, along with the content of what they said, with their organizations' supporters and with the news media. And, when advocates get their point of view included in news stories, or get their opinion pieces published, they should share the coverage with supporters and legislators so they benefit from advocates' published, concise opinions.

Recommendations for reporters

It is reporters' job to ask the hard questions, and there are many hard questions when it comes to determining the best nutrition policies for schools. And there is no shortage of controversy, as this study documents. Reporters can get to the heart of the matter when they go beyond the usual questions and the usual suspects to investigate what brought soda and junk food into schools in the first place. For example, reporters can:

- Investigate what teachers think about soda and junk food bans. Teachers experience the consequences of such policies in the classroom. What do they think of the bans? Do they notice a difference in their students' behavior or academic performance?

- Investigate why schools are so strapped for cash.

The argument is made that schools depend on the money generated from the sale of sodas and other non-nutritious foods to fund needed school programs. Yet rarely is the underlying question asked: Why don't schools have the money they need for basic supplies and activities? Journalists can use the controversy over restricting soda sales in schools to uncover the roots and history of schools' funding problems. - Investigate soda contracts.

Research is beginning to demonstrate that schools are not getting a good deal from soda contracts.18 Journalists can ask: Who profits? How much of the revenue generated actually goes to fund the activities for students? Why do beverage companies want to be in schools? - Investigate the consequences of laws and promises.

Experience with removing sodas from schools is beginning to accumulate. What happens in schools after sweetened beverages are no longer sold? What have soda companies done since making their pledges with the Alliance for a Healthier Generation? Did the companies keep their pledges? Are there fewer sugar-sweetened beverages and less snack foods in schools? How did the students and teachers fare?

School nutrition policy remains controversial. In 2006, the four states we studied — Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts and Maryland — introduced legislation to improve the foods and beverages offered in schools, but only Connecticut and Indiana passed legislation. News and opinion coverage can influence how the public and policymakers understand and respond to public health issues like creating healthier school nutrition environments. As these debates continue, public health advocates should be sure their perspective is included in news and opinion coverage and at the policy level, whether local, state, or national. And reporters should ask the hard questions so the public understands the benefits, and limits, of its policies.

Issue 17 was written by Lori Dorfman, DrPH, Eliana Bukofzer, MPH, and Elena O. Lingas, DrPH, MPH. Eliana Bukofzer, MPH, and Cozette Tran-Caffee coded the articles.

Issue 17 was supported by a grant to the Berkeley Media Studies Group from The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Issue is edited by Lori Dorfman.

© 2008 Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute

References

1 Center for Science in the Public Interest. Liquid Candy: How Soft Drinks Are Harming Americans' Health. June, 2005. Available via: http://www.cspinet.org/liquidcandy/index.html, accessed on October 3, 2008.

2 Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of Soft Drink Consumption on Nutrition and Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 2007; 97(4):667-675.

3 Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Relation between consumption of sugarsweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. Lancet, 2001; 357(9255):505-8.

4 Berkey CS, Rockett HRH, Field AE, Gillman MW, Colditz GA. Sugar-Added Beverages and Adolescent Weight Change. Obesity Research, 2004; 12(5):778-88.

5 Alliance for a Healthier Generation. Alliance for a Healthier Generation -- Clinton Foundation and American Heart Association -- and Industry Leaders Set Healthy School Beverage Guidelines for U.S. Schools. May 3, 2006. Available via: http://www.healthiergeneration.org/media.aspx, accessed on October 2, 2008.

6 Alliance for a Healthier Generation. President Clinton and American Heart Association Announce Joint Agreement Between Alliance for a Healthier Generation and Food Industry Leaders to Set Healthy Standards for Snacking in School. October 6, 2006. Available via: http://www.healthiergeneration.org/media.aspx, accessed on October 2, 2008.

7 Lingas EO, Dorfman L. Obesity Crisis or Soda Scapegoat? The Debate Over Selling Soda in Schools. Berkeley Media Studies Group, January 2005. Issue 15. Available via: /publications/issue-15-obesity-crisis-or-soda-scapegoat-the-debate-over-selling-soda-in-schools/ accessed on August 25, 2008.

8 The Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004: Public Law 108-265. 2004. Page 38-39.

9 Alliance for a Healthier Generation. President Clinton and American Heart Association Announce Joint Agreement Between Alliance for a Healthier Generation and Food Industry Leaders to Set Healthy Standards for Snacking in School. October 6, 2006. Available via: http://www.healthiergeneration.org/media.aspx, accessed on August 25, 2008.

10 A frame was counted each time it appeared. An article could have several appearances of a frame, or none at all.

11 Graf, Rosemary. Back state efforts to fight childhood obesity. The Berkshire Eagle, January 24, 2006.

12 Dixon, Ken. State Senate votes to take soda out of schools. Connecticut Post Online, April 21, 2006.

13 Connecticut Post Online. An untimely death for nutrition bill. Connecticut Post Online, April 6, 2006.

14 Rosen, Jill. Bills would require weight checks at schools. Baltimore Sun, February 26, 2006.

15 Martin, John. School lunch bells signal dash for vending machines. Evansville Courier & Press (Indiana), February 28, 2006.

16 Tuohy, John. The choice is theirs; Kids say they're driven by cost, not health, The Indianapolis Star, February 26, 2006, page B1.

17 Dunlea, Christopher. Soda and schools. The Boston Globe, May 14, 2006, page C10.

18 Ashe M, Feldstein SG, Kline R, Pinkas D, Zellers L. Local Venues for Change: Legal Strategies for Healthy Environments. Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics, Spring 2007:138-147.