How to make the roots of inequality more visible in the news

by: Lauryn Claassen

posted on Wednesday, January 16, 2019

Think about a public health or social justice issue you feel passionate about and ask yourself: Is it on the public’s radar? Does prevention seem possible? Are solutions frequently framed as actions that individuals must take, or is the shared responsibility of our institutions and government clear?

Because news coverage affects the way the public — and policymakers — view problems and what to do about them, we at Berkeley Media Studies Group continually strive to answer these questions by studying how the media characterize health and equity issues.  We then harness lessons from our research to help journalists improve their coverage and to help advocates work more closely with reporters to shed light on important issues that affect our daily lives and well-being.

We then harness lessons from our research to help journalists improve their coverage and to help advocates work more closely with reporters to shed light on important issues that affect our daily lives and well-being.

But the learning process isn’t a one-way street. To better understand the ever-evolving media landscape and to ensure that our recommendations are actionable in real-world situations, we regularly talk with advocates and journalists about the challenges, setbacks, and successes they’ve experienced.

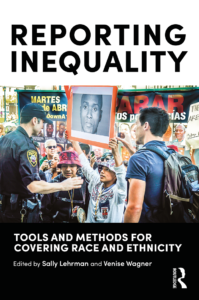

One of these individuals is Venise Wagner, a longtime reporter, associate professor of Journalism at San Francisco State University, and co-editor, with fellow journalist Sally Lehrman, of “Reporting Inequality: Tools and Methods for Covering Race and Ethnicity.” Forthcoming in February, the book offers strategies for journalists to go beyond conventional reporting techniques and more effectively cover the structural inequities that fuel racial and health disparities.

I recently spoke with Venise to find out more about the benefits and challenges of community reporting, why newsrooms need to prioritize staff diversity, and how advocates can build stronger relationships with reporters. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

For the uninitiated, what is community reporting, and how does is it different from conventional reporting?

In community reporting, reporters don’t see themselves as separate entities, or as flies on the wall, watching and seeing what is going on. Rather, they see themselves as stakeholders. Of course, they still must be careful of bias, but they understand that they have a stake in what happens in their community.

There is also an attempt to really have a deep conversation with communities. Rather than just writing about the community, you’re checking in with the community to find out what their needs are and even including them in the direction of the reporting. That is, depending on what they say, that helps direct where the reporting goes.

I’ve heard a lot about the idea that reporters must remain objective and can’t be advocates. Is that a problem with community reporting? Have you encountered any resistance about community reporting from journalists or your students?

I don’t think you have to be an advocate to be connected to your community. You’re not advocating for any one issue — you are writing in the interest of your audience. If you really are a member of the community, then you write about what has an impact in the community in which you live.

Your book, “Reporting Inequality,” discusses ways to enhance community reporting and show the roots of structural inequities. What do you hope journalists will take away from the book?

Our book focuses on helping reporters write about the policy rather than the individual — to really look at the impact of policy on people’s lives that leads to disparities.

BMSG always encourages reporters to incorporate a focus on systems, but, at the same time, individual stories can help draw a reader in and make abstract issues a bit more relatable. Do you have any suggestions on how journalists can strike the balance?

Yes, I think you need the individual story, but you have to be careful how you tell it. First, you need to look at the system, at a policy, and then you use the individual to show the impact that a particular policy has on people’s lives.

You also have to incorporate patterns and data, and then use the individual story to illustrate the impact of those patterns. It can be tricky because it’s hard for the audience not to focus on the individual, but journalists have to make sure they’re showing the bigger picture, which is why it’s very, very important to keep bringing it back to the policy.

We talked about how, ideally, in community reporting, reporters would not see themselves as separate from the community. But thinking about people who might be a little harder to reach — like immigrants — do you have any thoughts on how reporters can build trust with groups who might be nervous about talking with journalists or going on the record?

First of all, journalists have to give it time. They can’t just parachute into a situation.

And it’s hard — journalists have to go out and get the story, and they have multiple deadlines, and the demands on their time are greater than ever before. But if they’re going to get these really important stories, they have to be spending time in these communities without their notebooks. They have to be listening. They can’t just write about breaking news or show up when there’s a problem — they have to be there when there isn’t a problem.

Go to a community meeting, hang out and listen to people, get to know them, network — that’s now you build trust in the community.

What responsibility do you think newsrooms have to broaden their reporting and diversify their staff — and how do you recommend newsrooms go about that?

I think first it requires attitude adjustments. You have to really want to do this — you can’t just do it because someone is telling you to do it. Newsrooms have to support the idea that if they make the effort to diversify and make an effort to reach out to communities, they will reap a lot of benefit from it.

It’s not until they really see that that any kind of change can happen. And there are lots of ways to increase diversity in the newsroom. Newsrooms are always making the excuse that they can’t find qualified people of color, and I think that’s bunk. There are so many young journalists who are graduating from exceptional programs. There is no reason that they can’t find these people — they’re out there.

That reminds me of a report about diversity in the newsroom and WNYC reporter Tanzina Vega’s coverage of its findings. She had an amazing thread on Twitter giving her Top 10 tips for making newsrooms more inclusive, and one of them mentioned how the work can’t come in fits and starts but needs to incorporate it into their mission. I really loved that.

Yes, part of it is coming up with systems in the newsroom that allow them to be less biased in their hiring. What ends up happening is there is a certain look that a reporter has to have — if you are an investigative reporter, you are a white male. Maybe some white females, but rarely do you see investigative reporters who are people of color, and that is because newsrooms view white men as being arbiters of truth, as being the characters who can actually do this kind of difficult work. A lot of it has to do with the perspective of editors who think certain people belong in certain roles.

Do you think that is because newsrooms feel that community reporters can’t hold their own communities accountable?

I’ll be really blunt here: There is this idea that a reporter of color covering their own community cannot be objective, but why is it that there is this way of thinking? We don’t say that about white reporters covering white people. So why do we have this notion that reporters of color can’t be objective when writing about their own communities?

On the other hand, sometimes editors look at reporters of color and think, “Oh, I need to cover a story that’s in the Black community, and so I’ll send them.” But just because the reporter is Black doesn’t mean that reporter has access to that community. If that reporter hasn’t done the work, then they’re still not necessarily going to have access.

Sometimes as a reporter of color, you may think you can get access, but it doesn’t necessarily mean you have access to all parts of the community. There will always be barriers. Remember that privilege takes many different forms, and so I think that what a reporter of color has to remember is that they still have a position of privilege, and when entering any community, they still need to keep that in check.

So it kind of goes back to that idea of not parachuting in.

Exactly. So, the upside of having community beats, like we had when I worked at the San Francisco Examiner, is that sometimes you do get access. The downside is that what often ends up happening is those beats are marginalized within the newsroom. Coverage of communities of color can’t just happen by reporters of color. There has to be a concerted effort by everyone in the newsroom to consider stories that are happening — and I don’t mean just problem stories or breaking news stories, I mean stories that are really happening in the community. There has to be a concerted effort for reporters across beats to look at these communities.

Switching gears a bit and thinking about advocates who often have strong community connections and are trying to get media attention, do you do you have any thoughts or tips on how advocates can build stronger relationships with journalists or people in the newsroom?

They have to pay attention to who is covering what in their community by studying the bylines. Once they figure that out, then they can see which reporters to go to.

And then how can they reach out? Is it sending news releases, inviting them to community meetings, coffee dates, reaching out on social media?

I would say all of the above. The thing that activists and advocates have to remember is that reporting is about relationships. So, one way to make sure that your voice gets heard is to build relationships with people in the newsroom. Be sure to make phone calls when the news isn’t happening. Just say, “Hey, I think you might be interested in this meeting, and I’d like to include you just so you can get a sense of what is happening in our community.” That kind of thing.

“Reporting Inequality” will be available in February and can be pre-ordered from Amazon.