Introduction

Overdose prevention saves lives. While there are many successful and proven strategies for overdose prevention, substance use treatment, and harm reduction, they are not well-known or widely available. Worse, they are characterized as controversial and plagued by misinformation.

For many people living with substance use disorder or people who use drugs, including prescription opioids and illicit fentanyl, there are many barriers keeping them from receiving adequate and high-quality information and care, which can lead to poorer health outcomes and increased risk of death, particularly among Black, Indigenous, communities of color and LGBTQ+ communities.

While some have taken to social media to share life-saving information, local leaders and advocates are continuously working to counter misinformation, stigma, and pushback from the public, service providers, law enforcement, and government leaders.

To support advocates and local leaders in their efforts to communicate effectively about substance use treatment and overdose prevention, the National Overdose Prevention Network (NOPN), based at the Public Health Institute’s Center for Health Leadership and Impact, partnered with Berkeley Media Studies Group (BMSG) to develop messaging and communication resources.

This guide provides recommendations and resources for local leaders and advocates developing strategies to communicate about overdose prevention with a range of audiences. It includes examples that focus on key issue areas that emerged from our conversations with experts: stigma against people who use substances, pushback against policies like harm reduction efforts and substance use treatment, and unique considerations for rural communities.

What we did: BMSG researchers analyzed existing resources from around the U.S. on communicating about overdose prevention, including toolkits, webinars, and reports. We also interviewed a range of overdose prevention experts across rural and urban California, including physicians, outreach workers, health educators, law enforcement, and coalition leaders to gain first-hand insights into the unique challenges and opportunities they see for effective communication about overdose prevention. We engaged with additional reviewers with expertise in overdose prevention to evaluate sample messages and provide recommendations for improvement.

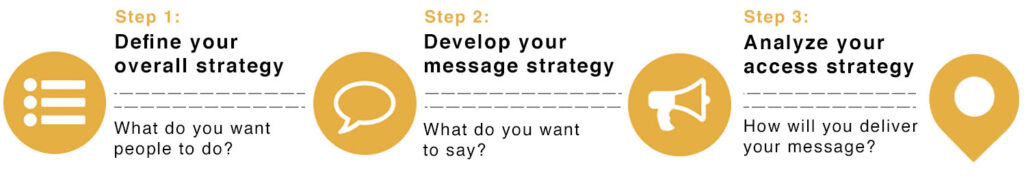

Our hope is that leaders and community supporters will use this guide as a resource for ideas whenever they need to talk about overdose prevention. We offer a roadmap with concrete recommendations to develop effective, strategic communications:

- Step 1 describes “overall strategy” — the reason messages are developed, and the context in which messages are delivered. We start there because before you can have an effective message, you need to know your overall goal and have a plan for achieving it. You can think of your overall strategy as the destination for your roadmap.

- Step 2 offers concrete advice on constructing messages that help people manage complicated views about substance use and move them toward supporting overdose prevention efforts. You can think of your message strategy as signs to guide your audience towards your destination or overall goal.

- Step 3 provides recommendations for getting your messages out to your target audience (in other words, your access strategy) and preparing for communication challenges. You can think of these as routes to reach your desired audiences.

These steps are informed by BMSG’s approach to and experience in strategic communication, and each of the recommendations is grounded in our analysis of advocacy materials and interviews with experts. Throughout the guide, you will also find links to resources from NOPN and other groups to build on these recommendations and provide additional information.

Step 1: Define your overall strategy: What do you want people to do?

Before you can decide what to say, you must know what you want to change, who has the power to change it, and why it needs to be changed. In other words, message is never first. Often when people don’t know what to say, it means they don’t know what to do.

A clear overall strategy helps to define your “destination” or goal. With a specific and well-defined goal, you can increase the effectiveness and efficiency of your communication: It will help you allocate time, money, and effort towards reaching that goal or destination.

Key questions for your overall strategy

What issue or problem do you want to address?

How you define the problem affects how people think about solving it. In trying to communicate about how big, and how important, overdose prevention is, it can be tempting to try and say everything that you know about overdose prevention any time you have the opportunity to talk about it. Resist that urge, and remember: it is impossible to be comprehensive and strategic at the same time.

Instead, to make your statement of the problem clear and understandable, focus on just one aspect. Once that portion of the problem is being addressed, you can shift your message and goals to focus on another piece, based on your overall strategy.

Sometimes it’s frustrating because if you’re naming one thing, you are not naming another. But the fact is, in most instances, you can’t push for everything in every moment. And, in fact, it can be helpful to remind audiences that your effort is one of many approaches needed to address this important issue.

What solution will you propose?

You’ll know your solution is specific enough if you can answer the five Ws (though you won’t necessarily need to include all five in every message): Who should take action? What should they do? When should they do it? Where will it happen? Why is this the right approach? Some examples of solutions could be: making Naloxone more available, approving a syringe services program, or increasing access to medication assisted treatment (MAT) like buprenorphine or methadone.

Who has the power to make the change?

Clarify who can advance the solution you’re proposing. Consider clinicians, law enforcement, or your local board of supervisors. Some questions to consider: Is your primary audience a person or a group of people — for example, the representatives of an institution? What would happen if your solution made someone else responsible for solving the problem? Who would be accountable? Would that help you?

How will you influence your audience?

There are different factors that may help your primary audience to use their power to make the change you seek. Consider the following: What motivates your target audience to act? What is your relationship with the target audience? How do you have influence with them? Is it as a neighbor, colleague, voter, consumer, stockholder, or some other way? What tactics might be most effective to reach your target?

What allies can help you make your case?

When you analyze your community, coalition, or partners, you may find allies who have stronger connections with your primary audience. Think about parents, educators, first responders, pharmacists, coalition leaders, clinicians, people who use drugs, people who have lost loved ones, and others. Who has the power to influence your target audience and strengthen your case?

Strategies for overdose prevention

Your overall strategy should consider the different “doors” through which people may be entering overdose prevention work. As you develop your overall strategy, consider the range of overdose prevention solutions, partners who support and provide those solutions, and the gaps you may be looking to fill. NOPN’s Partnership Mapping Tool is a helpful resource and, on page 3, you can see how to apply the Overall Strategy to their four issue areas to:

- PREVENT new addictions (e.g., upstream prevention and education; safer prescribing practices; drug disposal and takeback; trauma informed communities; behavioral health integration)

- MANAGE pain safely (e.g., alternative pain therapies; tapering high dosages; limiting opioids + sedatives)

- TREAT addiction (e.g., access to medication assisted treatment; contingency management; counseling; stigma reduction)

- STOP overdose deaths (e.g., naloxone training and distribution; syringe services programs; fentanyl testing)

Defining your audience

Once you have clearly defined the issue (or problem) and solution to address that issue, you can think about who has the power to make the change. Your primary or target audience is the person or people who can advance your goals. Secondary audiences may be allies or people who can help you reach and activate your primary audience.

Remember that, depending on your audience and their approach to addressing substance misuse, there may be different starting points, opportunities, and challenges to advocating for your solution. Some people may be supportive of some solutions (like preventive solutions), but push back on others (like naloxone training and distribution programs).

In general, whatever your strategy, consider audiences who are “movable” on your issue and may be open to hearing more about solutions, even if they are initially skeptical or fearful. While it may be tempting to focus on changing the mindsets of your strongest or most vocal opponents, there are other audiences that can be “moved” more easily who are likely a better focus of your time and energy.

Resources to help define your audience

Crafting a Persuasive Narrative, Part 1: Knowing Your Audience and Messaging Appropriately:

Communications professional Michael Miller introduces the most essential element of all communications: knowing your audience and speaking to their sensibilities. This workshop shows you how to develop memorable and action-oriented messages.Power Analysis by Othering & Belonging Institute:

Analyze how people and groups relate to your goal or vision based on how much they agree, or disagree, with your goal – and the power they have to advance or hinder your work.

Building partnerships and coalitions with new partners

We heard from experts that building partnerships and coalitions is key for successful overdose prevention strategies. However, you may encounter tensions or conflicts when you bring different audiences, allies, advocates, and partners to the same table. The experts we spoke with suggested that, when building relationships with new partners, it’s important to:

- Listen without judgment: "Let's just hear from one another. Because you both have really incredible experiences and we shouldn't be making these judgments just because you're a cop or just because you run a needle exchange."

- Build empathy: It was just really helpful for us to hear from [our partners] that they're human, and they had some really horrible experiences and saw some really difficult things and for us to see how that lens goes into their work.

- Focus on their shared goal or vision: "We can all work together and have exponential success if we put our oars in the water at the same time, move in the same direction."

Additional considerations for audiences

Some of the experts we spoke with named audience groups who are uniquely important, but are sometimes overlooked in conversations about overdose prevention. Consider that your target audience may include people from these groups who may have some specific concerns to keep in mind.

Table 1. Considerations for communicating about overdose prevention with unique audiences.

| Audience | Notes and resources |

| Black, Indigenous, communities of color (BIPOC), and non-English speaking communities | Some experts shared that some people may not trust healthcare providers, criminal justice representatives, public health professionals, or local government officials, even if they are BIPOC themselves, because of these systems’ historical and ongoing harm on BIPOC communities. Improving the quality of relationships with BIPOC substance users is important for building trust, decreasing stigma related to race and substance use, and increasing access to overdose prevention strategies for BIPOC communities. Resource: Recommendations for Programs and Funders Who Serve People Who Use Substances: Disrupting Structural Racism's Impact on Health |

| Children and youth | A few of the experts we spoke to discussed the importance of partnering with schools to educate students on prevention. They advised focusing on healthy coping and relating skills, as well as safety and mental health support resources. For example, they suggested avoiding the details of harm reduction and instead talking about naloxone at a high-level to help build support from parents, caregivers, or therapists who work with young people. Resource: Let's Talk: A toolkit for navigating teen substance use in the tri-county region: Monterey, San Benito, Santa Cruz. Resource: Youth Engagement |

| Caregivers and parents | Some experts shared that caregivers and parents may react positively to talking about overdose prevention, while others who are actively experiencing loss or fear losing a family member may react negatively. Consider trauma-informed approaches with people who have lost children or family members to overdose. Resource: Substance Use Prevention Resources for Adult Role Models |

Meet people where they are — literally.

Several of the experts we spoke with emphasized the importance of meeting with audiences in their communities. Look back at your overall strategy and consider where you might find your target audience.

Outreach workers we spoke with suggested going to densely populated areas where people live (like apartment complexes, mobile home parks, encampments); places where they can get their basic needs met (like food, clothes, healthcare); or where they gather with community (like Rotary Clubs or places of worship). As one interviewee noted, “I will set up my folding table and all of my materials in parking lots of central community locations. Sometimes it's in a gas station parking lot, outside a library, outside of schools, or alongside different food distribution programs.” Tribal communities may be more dispersed, so you may not find “densely” populated areas there. As one expert shared, you may connect with caseworkers at Tribal courts and emergency rooms to gather more insights about the community.

Some experts also highlighted digital access issues and recommended preparing for in-person meetings with audiences who might prefer that format rather than Zoom or online meetings, like audiences who speak different languages and need translation support.

It is also important to “meet your audience where they are” in terms of their level of understanding and how much they may (or may not) accept your solutions. Some experts recommend smaller groups to introduce concepts on a more personal level. You will want to plan for space and time for storytelling, education, and questions. Change usually doesn’t happen all at once, so experts we spoke with recommended timely and quick follow-ups.

If your target audience includes government leaders with staunch “anti-drug” views, you may need to consider more grassroots tactics to engage and move forward in partnership. For example, you may want to approach individual government leaders directly and privately to build more trusted connections.

You may also consider listening sessions and invite different perspectives. Some people or groups may have historical conflicts or tensions that they bring to the table. It is important for the convener or facilitator to be as neutral as possible to negotiate bringing groups together. There may be many “experts” with different solutions, so reminding your group of a shared goal, outcome, or vision (for example, of a community with fewer overdose deaths and more safe, healthy residents) can help to overcome those conflicts and tensions.

Putting it into practice

Sample overall strategies

Example #1: Stigma

- What issue or problem do you want to address? Overdose death rates among adolescents have increased since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Naloxone prevents overdose death and saves lives. Stigma about harm reduction approaches like naloxone prevents adolescents from having access to life-saving resources.

- What solution will you propose? Policy to have naloxone available on school campuses and ensure all teachers and coaches are properly trained on its use.

- Who has the power to make this change? School board leaders, school administrators, state board of education, and/or county office of education.

- How will you influence your audience? Present at board meetings and public campaign.

- What allies can help you make your case? Parents, teachers, and/or students.

Example #2: Harm reduction

- What problem or issue do you want to address? Heightened rates of overdose due to funding cuts to harm reduction programs and decreased access to naloxone and safer use supplies.

- What solution will you propose? Reinstate funding to harm reduction programs.

- Who has the power to make this change? Public health department and government officials.

- How will you influence your audience? Present at city council meetings and conduct 1-on-1 meetings with government officials.

- What allies can help you make your case? First responders, doctors, and/or people in recovery.

Considerations for developing strategy in rural communities

Your ability to be mobile and accessible will help you to reach more audiences, especially in communities that are more dispersed and spread out. No one person or organization can do it all with limited resources and building local coalitions can help to expand your reach and mobilize the entire community to act. Rural coalitions work by assessing the community and the issues of greatest concern, then identifying a capacity for strengthening old bonds and starting new partnerships before formulating a strategic direction.

- Partnerships & Rural Coalition Building — Overdose Prevention in Rural Communities: This resource from NOPN provides several links to tools, strategies, and techniques for building and managing coalitions with community partners.

- Mobilizing Community Partnerships in Rural Communities: This resource provides tips on communicating and engaging with new partners in rural communities, such as:

- Clearly establishing and communicating how your organization’s goals align with those of your potential partner.

- Emphasizing the benefits of the partnership for your potential partner organization, based on careful study of the organization’s mission, vision, goals, and objectives.

- Opting for tailored messages and approaches when trying to engage partners; avoid standardized form letters.

- Stressing the importance of your potential partner’s inclusion.

Step 2: Develop your message strategy: What do you want to say?

Once you have defined your goal, solution, and target audience in your overall strategy, you have your “destination” to guide the rest of your communications. Next you need to figure out how you can move your audience towards your goal by preparing your messages or “signs” on the route to your goal or destination as defined by your overall strategy. Here are some questions to consider when developing your message strategy.

- How will you frame your message?

- What shared values can you appeal to in your message?

- How can you use language that many people will understand and respond to?

- What spokesperson can deliver the message? How will you prepare them?

- What data, visuals, and other materials do you need to make your case?

In this section, we’ll go through each of these questions and provide resources for additional background.

How will you frame your message about overdose prevention?

Framing and why it matters

We all come to new information with ideas already in our heads about the way the world works. Those existing notions form the mental structures (“frames”) that allow us to integrate new information into our brains in a coherent way. Without even knowing it, we use frames to categorize information, identify patterns and create meaning from them. Frames can foster certain understandings and hinder others: they create tracks for a train of thought, and once on that track, it’s hard to get off. Often, all it takes is a single word or image to activate an entire frame that then determines the deeper meaning of that word or image. Once activated, frames trigger emotions, associations, values, judgments, and causal explanations.

Understanding the frames that audiences hold about substance use and overdose prevention can help to identify messaging opportunities, or anticipate “roadblocks” to effective communication. People can hold multiple, even contradictory, frames in their heads at the same time. The one that gets triggered and repeated more often has a better chance of influencing people’s interpretation of the message. One of the most dominant narratives in the U.S. is “individualism” — the idea that “you’re on your own” or “you’re to blame.”

The dominant frame affects how people understand substance use and misuse: the California Health Care Foundation wrote, “decades of misinformation about substance use and overdose prevention has created a culture of blame and the false belief that willpower alone enables recovery.”

Many of the frames people hold about substance use may reinforce stigma, a major barrier for people with substance use disorder and people who use drugs. Negative perceptions about substance use can contribute to inequitable care for people with disorders like opioid use disorder, and individuals may choose to conceal their substance use problems to avoid stigma, which may result in medical or legal care that does not attend to substance use-related needs, or pushback against policies that could support treatment and overdose prevention. For example, our research revealed that:

- Some healthcare providers may believe that people with substance use disorders and people who use drugs overuse resources, are not invested in their health, do not adhere to treatment, or abuse the system.

- Some law enforcement officers may believe that it is unsafe to have physical contact with someone experiencing an overdose or poisoning, or may resist harm reduction strategies like naloxone if they are framed as “required” or “mandatory.”

- Some staunchly anti-drug leaders may reject solutions like harm reduction, or not even acknowledge substance use in their communities.

- Some community members may be supportive of harm reduction solutions like naloxone (or naloxone), but may oppose other solutions like fentanyl test strips or syringe exchange programs, which they see as “a step too far” that enables substance use.

Reframing substance use and overdose prevention

We identified some dominant frames that pose “roadblocks” to your target audience’s understanding of and support for solutions to prevent overdose and treat substance use. The table below includes dominant frames found in our research, explains why they are problematic and harmful, and suggests opportunities for reframing to get your audience on a path towards supporting overdose prevention and substance use treatment.

Table 2. Framing challenges and opportunities when communicating about overdose prevention.

| Dominant frame | Why it's a problem | Reframe |

| Drug use is “wrong” or “dirty.” | Words like “dirty” or “wrong” are associated with filth and may prompt shame or evoke bias towards punishment-based solutions. | Avoid saying that drug use is “wrong.” Instead, describe substance use disorder as a chronic health condition. Do not talk about people getting “clean.” Instead, talk about how people can make improvements in their lives. Use metaphors or analogies to make it easier for your audience to understand complex and abstract issues. For example, this video about framing provides this analogy, “Addiction is a disease, like diabetes is a disease. Would you deny somebody an insulin injection?” |

| Drug users are “addicts” or “junkies.” | Terms like “drunk”, “addict” and “junkie” imply an affected individual causes their own illness and can lead to less sympathetic responses (e.g. incarceration) instead of overdose prevention and substance use treatment. | Move away from describing substance use disorder as an identity. Instead, use person-first language: for example, say “people with substance use disorder” and “people who use drugs.” Exposing people to personal stories may help to build empathy and understanding and reduce stigma. Share stories from your own eyes or through the eyes of somebody’s experience about substance use, the reality of overdose, going through recovery, or losing someone to opioids or overdose. For more resources, see Appendix: Storytelling resources to reduce stigma. Personal stories and quotes (or “portrait” frame) should also be expanded to show the context and root causes (or “landscape” frame) of substance use to help people better understand what impacts our health and bring concrete, systemic solutions into the picture. For more on effective framing, see BMSG’s Framing 101. |

| People need to “hit rock bottom” before they seek help. Or Recovery isn’t worthwhile because people relapse. | This frame embodies a dangerous misconception of the nature of opioid use disorder. Research shows that long-term opioid use alters brain chemistry in a way that produces uncontrollable cravings and intense despair that can persist years after last use. “Hitting rock bottom” frequently means overdose death. It also obscures the historical context and root causes of opioid use disorder. | Talk about substance use disorder as a chronic condition. Use analogies to help people overcome fatalism and doubt. For example, “Addiction is a chronic illness, and relapse is part of the disease. It takes smokers an average of 30 or more attempts before they stop for good.” Illustrate the context in which people develop substance use disorder to shift away from individual blame and towards systemic responsibility. For example, “Opioid medications were heavily marketed and promoted as safe and risk-free medications to doctors starting in the 1990’s. Over-prescribing was the norm for so many years that the effects of opioid use have spread nationwide.” For more strategies on managing pushback, see MAT for Opioid Use Disorder: Overcoming Objections. |

| Harm reduction enables drug use. | This frame reinforces stigma and misinformation about strategies to treat substance use and stop overdose deaths. | Emphasize that harm reduction is health care, just like doctors “reduce harm” with medications to treat other diseases. There are decades of evidence supporting medication and treatment for substance use disorder. Compare harm reduction strategies to life saving tools like fire extinguishers, smoke alarms, and CPR that help you to be prepared. For example, “Naloxone is like a fire extinguisher. We all hope we don't have a house fire, we don't think we're going to have one, but you want to be prepared if you have one.” Share evidence that harm reduction saves lives by reducing overdose, improving morbidity and mortality, and reducing communicable disease transmission. This video by the California Department of Public Health delves into objections to harm reduction and how to respond effectively. |

| “I don’t use drugs personally/there are no drugs in my [community / school / etc.], so it’s not my problem.” | This “not in my back yard” (sometimes referred to by the acronym “NIMBY”) perspective creates an “other” group to make the issue seem further away or disconnected from you. It also ignores the reality of how widespread, and often hidden, substance use disorder is. | Use metaphors that convey the importance of prevention and a sense of urgency “We don’t want someone to have to die to make change”: One expert we interviewed shared a metaphor of a missing traffic sign: they noted that the county might point to the lack of traffic accidents to justify not fixing the sign - until someone crashes and is injured or dies. “Let’s be prepared for the hard conversations”: Another expert compared education about substance use to sex education, saying “We know by us saying ‘don't do it’ it's not going to make kids stop having sex. It's similar with substance use. Let's prepare them and let's have open dialogue as a community and as caregivers and parents.” Bring in data and evidence to illustrate the indiscriminate nature of substance use disorder and overdose. For example, one in seven Americans in their lifetime will have a substance use disorder. For more resources on data, see Appendix: Data and statistics to support your overall strategy. |

| If I help somebody experiencing an overdose or using substances, I will get in trouble myself. | This frame falsely affirms that bystanders cannot do anything when they see someone experiencing an overdose. | People are sometimes afraid, hesitant, or reluctant to report an overdose or problematic behavior because they may suffer consequences themselves. You can remind people, especially law enforcement and government officials, of Good Samaritan laws, which allow people to report an overdose without risking arrest. |

| Recognizing and treating overdose is complicated. | This suggests that supporting people using substances is beyond the abilities of bystanders. | Use metaphors and analogies to extend support to people using substances or experiencing overdose, and show the importance of non-judgmental provision of services: One expert we interviewed said, “There are some people out there on the streets that you do probably have interaction with that could benefit with more regular involvement with people from prevention. Because it extends the olive branch and it eventually leads to some treatment if that's what they want.” “If you're a smoker and every time I walk past you outside my building I say ‘You know that's really bad for you.’ You don't avoid smoking, you avoid me.” (Source: Alessandra Ross, MPH, CDPH, Office of AIDS - Responding to Objections to Harm Reduction) |

Crafting your message

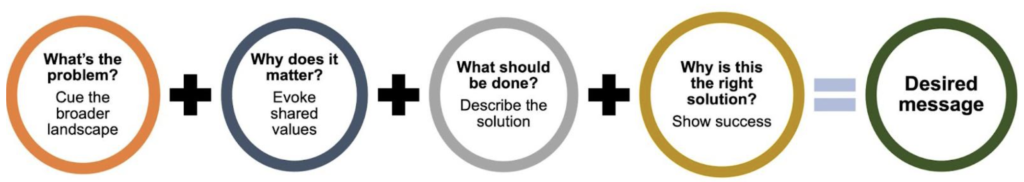

With an understanding of the framing challenges and opportunities that underlie conversations about overdose prevention, we can use the following building blocks to develop messages that help our audiences see overdose prevention as a necessary and achievable public health measure.

Figure 1. Elements to create and frame your desired message.

- What is the problem or issue? Answer: Your perspective on what has gone wrong. Make sure to define your problem precisely so that it cues up your desired solution or goal.

- Some audiences may ask for “evidence” to better understand the problem. Here are some data points and statistics identified in our research to help articulate the problem you are trying to solve.

- When available, local data and statistics are powerful and this measurement guide by the California Overdose Prevention Network provides some ideas for evaluating your efforts.

- Why does it matter? Answer: Your target audience’s core values

- What is the solution? Answer: Who should take what action, by when

- Why is this the right solution? Answer: Show success with examples, stories, and data to illustrate that change is possible and help audiences overcome skepticism

Values

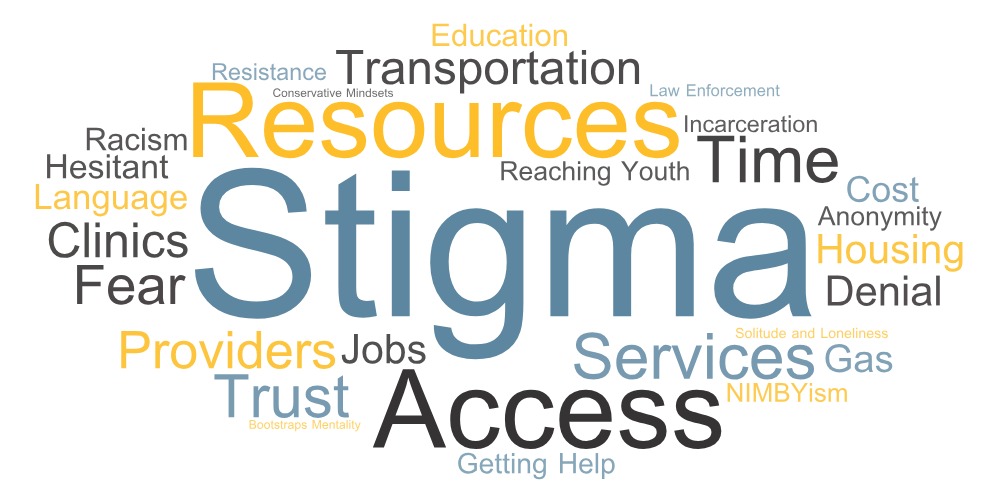

An effective message reaches people not just in their heads but in their hearts. Our values — like unity, dignity, and safety — are what motivate us, far beyond facts or figures. Effective messages need to explain why overdose prevention efforts matter for everyone, even those who may not always see a personal connection. Express your values to build a vision of where you and your community want to go together that includes what overdose prevention should look like during this urgent moment and in our future.

This image of a word cloud highlights values that surfaced in our research that could be adapted for your messages.

Figure 2. Values that may be adapted when communicating about overdose prevention.

Since so many dominant frames around substance use create divisions between people who use drugs and their communities, some of the most effective values are ones that emphasize interconnectedness, such as:

- Community: “Opioid abuse or misuse is a community-wide epidemic that will require a community-wide response.”

- Love: “The Native way is, the person is loved no matter what they do, so it's unconditional love … in order to understand who a person is, you get to know them and you as a person behave in such a way that you become their auntie or uncle.” – Interview with Tribal community advocate

- Collaboration: “We can all work together and have exponential success if we all put our oars in the water at the same time, move in the same direction.” – Interview with law enforcement expert

One effective and simple way to reframe is to use the words like “our,” “we” or “us”” when you express these values to convey interconnectedness, and illustrate that families and communities have a shared commitment to preventing overdose.

Values like responsibility, common sense, and stewardship may be more appealing for audiences who hold firm “anti-drug” sentiments. These values include:

- Responsibility: "Narcan is a tool. This is a tool for you to use just like all the other tools you have on your tool belt." — Interview with former law enforcement officer

- Economic benefits: “Jail health systems have a powerful business case for streamlining access to MAT to avoid the high costs of overdose treatment. MAT has been shown to lower emergency department and hospitalization costs, lower hepatitis C and HIV rates, and decrease overdose deaths.”

Be sure to use the value of “economic benefits” with other values like community and responsibility: focusing only on economic benefits could have the unintended side effect of making some audiences think about people with substance use disorder and people who use drugs as an economic burden.

Use plain language

When you’re developing your message or talking points, ask yourself: what is your audience’s level of understanding, literacy, or education? What languages do they use and prefer? Using plain language is one way to take a complex topic like harm reduction and make it relatable. Avoid jargon or that may not be well understood beyond people working in your field. This kind of technical or “insider” language may alienate your audience, or leave them with more questions than answers.

Table 3. Examples of jargon and possible alternatives in plain language when communicating about overdose prevention.

| Instead of… (jargon) | Try… (plain language) |

| Substance | Be specific: alcohol, cigarettes, cannabis, opioids are all forms of substances. Depending on your audience, consider using informal or commonly accepted terms. |

| Opioids | Pain medicine, pills, heroin, fentanyl |

| Polysubstance use | Multiple substances Be specific: people may use more than one “substance” at a time and some may not consider over-the-counter medications and alcohol to be “substances.” |

Should I say "poisoning" instead of overdose?

You may use analogies to illustrate poisoning, like “Overdose is like accidentally (or unintentionally) drinking water with cyanide in it.” Another example can be found in this TV news interview with a representative from the District Attorney’s office who reframed substance users as victims of poisoning from fentanyl.

The use of poisoning is widely debated — one article in The New York Times describes how it can, on one hand, reduce stigma and, on the other, further criminalize substance use and substance users.

Who delivers your message?

Trusted messengers are just as important as the message. From decades of research we know that audiences connect best with messengers who they see as similar to them in some key way. Not surprisingly, several experts also shared that “outsider” voices may not be as accepted or trusted when it comes to communicating about overdose prevention, so consider messengers from the same community as your audience, or who have shared experiences that they can highlight in their messaging. For example, depending on your overall strategy and goals, consider messengers who:

- Are people with lived experience, like those who have lived through overdose, treatments, recovery; personal experiences in emergency rooms, jails, peer support groups; and family and friends of individuals who have died from overdose, and parents who have lost a child to overdose.

- Reflect cultural experiences of Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, Pacific Islander, or migrant communities.

- Are long-time community members with deep knowledge of networks and history, who can speak to community members and other leaders to build partnerships.

- Represent government agencies like Substance Use Prevention and Treatment agencies who can speak directly to other government representatives.

- Work in medical care and can speak directly to leaders of hospitals, health organizations, and health and human services government agencies.

- Are pharmacists who can work with peers to conduct academic detailing on naloxone co-prescribing practices.

Are there people in your - or your organization's - networks who might be interested in and able to talk about overdose prevention solutions? If so, what kind of support might they need? Think about multiple kinds of support, including fair compensation for their time and energy as spokespeople and messengers, as well as trauma-informed care and support when revisiting and sharing about difficult and potentially traumatic memories.

Putting it into practice

Sample message strategies

Example #1: Stigma

Example scenario:

- Problem: Stigma about harm reduction approaches like naloxone prevents adolescents from having access to life-saving resources.

- Values: Safety, preparedness, health

- Solution: Policy to have naloxone available on school campuses and ensure all teachers and coaches are properly trained on its use.

- Success: Some schools in California have started to implement policies to make naloxone available on school campuses.

- Audience: School administrators, school district representatives.

- Messenger: Teacher

Example message:

I became a teacher because, like all of us in education, I believe that every child deserves to thrive, and I want to help them become the best possible versions of themselves. It’s hard to think about kids in our community using substances, but just because it’s an uncomfortable topic, we can’t let the stigma and shame associated with substance use keep us from being prepared for dealing with an overdose.

When students start experimenting with drugs, they might inadvertently ingest something they didn’t know was included like fentanyl or a stimulant. Therefore, our schools and teachers need to know how to respond properly to an overdose. I know this first-hand because I almost lost a student to an overdose while they were on campus. I felt shocked and scared and I didn’t know what I was allowed to do as a teacher.

This was a life-or-death situation and if we had naloxone available in our schools – like what we’re seeing with schools in Santa Cruz County – we could be better prepared for situations in the future – even though we all hope they won’t happen. That’s why I am calling on the school district to adopt a policy to make naloxone available on campus and for teachers and coaches to be properly trained on its use so that no student or teacher has to live through the trauma of having or seeing an overdose. This can show students and families that our community cares about the well-being of our future generations– even when it means having hard conversations.

Example #2: Harm reduction

Example scenario:

- Problem: Heightened rates of overdose due to funding cuts to harm reduction programs and decreased access to naloxone and safer use supplies.

- Values: Safety, fairness, health

- Solution: Reinstate funding to harm reduction programs

- Success: Research shows that harm-reduction programs can provide economic benefits in a 1-year time frame, and the largest benefit may become evident in the years ahead.

- Audience: Government officials, board of supervisors, public health department

- Messenger: Doctors

Example message:

We want people to be happy, thriving, and well. As a doctor in [name of community], I am proud to take care of my community. However, the reality is, one in seven people in our community are living with substance use disorder and when we’re not doing whatever we can to keep them safe, we’re not living up to who I know we are as a community.

Our ability to keep our communities healthy and well has been undermined by funding cuts to harm reduction programs that serve thousands of people a year. I’m scared to see what the future holds for our community if we don’t have those resources.

That’s why I’m calling on our government leaders to reinstate funding to harm reduction programs so that our communities have equal access to life-saving tools, care, and the things that treat the mind, body, spirit. Research shows that harm reduction programs can be cost-effective and save money in the long-term. By restoring funding, there’s a better chance that our friends and neighbors struggling with substance use disorders will be able to take an important first step toward the life-saving tools they need.

Considerations for developing messages in rural communities

Rural communities may face different challenges compared to urban communities. One of the major barriers for people with substance use disorder and people who use drugs in rural communities is stigma: the lack of anonymity when “everyone knows everybody” and fears of negative impacts on employment or isolation from their community can make obtaining substance use treatment and overdose prevention tools more challenging. Another barrier is accessibility: due to distance, scarcity, and uncertainty in opioid supply, staying well for substance users consumes significant time, money, energy — more than for those in urban areas.

As one Tribal expert noted: “In order to get your Suboxone and counseling, for some it’s 30 miles away. So if you don't have a driver's license, you can't legally drive, you don't have a working car or a bus system, or [you can’t get an] Uber because there's no electricity or Internet … You see all the challenges? It's everyday life.”

Remember that rural communities are not a monolith. Do not make assumptions about people living in rural communities – in fact, more likely than not, they are well aware of the issue and may be even more prepared to talk about solutions. When it comes to rural communities, a key question is how underrepresented communities can educate others and, if appropriate, reach larger and national media outlets.

Figure 3. Challenges and barriers to overdose prevention in rural communities.

To counter some of the dominant frames in rural communities, like NIMBYism and stigma, here are some values that emerged from webinar participants that you may consider when developing your own messages in rural communities.

Figure 4. Values that may be adapted when communicating about overdose prevention in rural communities.

Step 3: Analyze your access strategy: How will you deliver your message?

Once you’ve decided on your goal, and figured out what you — or your messenger — should say, it’s time to consider how you will get your solutions and messages out to the world and, more specifically, reach your target audience. Effective communication about overdose prevention can happen in many different places, from media campaigns to one-on-one interactions. In this section, we’ll review some strategies that can help make your message more impactful no matter where or how it’s delivered, and discuss the pros and cons of using media.

Prepare for communication challenges

Whether you’re using the media or not, you may find yourself facing difficult and challenging situations when communicating about overdose prevention. Whatever method of communication you’re using (one on one meetings, social media, news media, etc.), we’ve compiled possible communication barriers to anticipate, as well as recommendations for how to meet them that are grounded in the lived wisdom of the many experts with whom we partnered for this research.

How do you respond to misinformation?

Since misinformation is a key concern that many people encounter and worry about in structuring their communication about substance use and overdose prevention, plan ahead so you’re prepared to respond.

Avoid elephant triggers

Cognitive linguist George Lakoff describes how once someone says “don’t think of the elephant,” all you can think about are elephants. That’s why when you repeat your opposition’s argument, you’re activating an “elephant trigger.” We often stumble into elephant triggers when we focus only on rebuttals to our opponents. To avoid them, speak about why it matters to you, and talk about solutions in your own language.

- If you catch yourself saying: “This is not about…” or “We don’t want…” or “It’s not true that…”

- Stop and reframe: What IS this about? What do we WANT to achieve? What do we KNOW is true?

For example, instead of saying “It’s not true that harm reduction enables substance use.” Try, “Overdose prevention saves lives and protects our family, friends, and neighbors.”

Avoid repeating false claims by using a "truth sandwich"

Occasionally, public health practitioners may not be able to avoid addressing false claims, but repeating misinformation and false claims risks inadvertently amplifying and strengthening inaccurate information (another form of “elephant triggers”!). If you need to address misinformation, sandwich it between the facts about safety and widely shared values about protecting communities. When combined with shared values like trust and protection, this approach, known as a “truth sandwich,” may be an effective tool, one that journalists are also starting to use. Cognitive linguist George Lakoff’s recipe is:

- Start with the truth. The first frame gets the advantage.

- Indicate the lie. Avoid amplifying the specific language if possible, and don’t repeat what’s not true.

- Return to the truth. Always repeat truths more than lies.

For example, try saying: “Overdose prevention saves lives. There is a lot of misinformation out there about what overdose prevention looks like and how it works, but at the end of the day, we must be prepared to use every tool at our disposal to save the lives of our family, friends, and neighbors from overdose and poisoning.”

Resource for communication challenges

Communicating in Conservative Contexts: Strategies for Raising Health Equity Issues Effectively by Dialogue4Health: The FrameWorks Institute shares pragmatic strategies, including responding to misinformation for navigating toward justice in red-state terrain. Each recommendation is grounded in evidence from empirical research showing that reframing can help to build common ground on even the most divisive public health topics.

Is media the right option for you?

Before jumping at the opportunities for getting in the news, ask: How and when will news coverage advance your policy goals? That will help you choose your media access tactics and plan when to use them. The experts we interviewed offered guidelines that may help you decide what type of media might be the right fit to advance your policy goals:

- Traditional print and online news publications may be helpful to reach policymakers.

- Social media can help you reach younger audiences. Social media campaigns also allow for easier changes in direction compared to larger-scale, more bureaucratic campaigns. For example, social media can allow you to quickly change or adapt your language based on your audience.

- Audiobooks or podcasts may be helpful for people with different literacy levels or prefer listening rather than reading.

- Printed materials may be more appropriate for adults and seniors.

If news coverage will help advance your policy goals, consider how you will pitch your work to a journalist. Obviously, overdose prevention is important to advancing the health of communities, but journalists tell stories, not issues, and they cannot cover everything.

What could make your story compelling, timely, and meaningful to the audience of the news outlet? You can learn more in this manual “Communicating for Change: Creating news that reaches decision-makers” created by BMSG with The California Endowment. This resource explores different news story elements so advocates can get access to journalists by emphasizing what is newsworthy about their issue. Use this guide to learn how to create news, piggyback on breaking news, meet with editorial boards, submit op-eds and letters to the editor, and develop advocacy ads.

Considerations for using media in rural communities

If you decide to engage with the traditional print media, consider that rural communities have smaller media markets: local newspapers may serve multiple towns or may not have the staffing (or staff with skills) to write about these issues.

On the other hand, you may be able to engage directly with local reporters. Look for articles that reference the opioid epidemic and when you see news coverage about those issues, use those as an opportunity to write a letter to the editor to tell people about the work that you’re doing. You can also submit op-eds (opinion editorials) to share about upcoming activities or events.

Beyond traditional print media, rural communities may use alternative forms of media like social media. You may find your audience uses Facebook and social media groups where “closed” discussions provide more comfort, privacy, and safety. Citizen journalists may use newsletters or blogs to share information.

Finally, experts recommend considering grassroots tactics. Analog or printed materials to post on bulletin boards where people go (like grocery stores, churches, bars) may help reach aging audiences who may not be using social media. Remember that rural communities also go beyond county borders. Consider a regional strategy to build partnerships and expand your outreach and capacity.

“We realized that the patients cross county lines, the providers cross county lines, so the communications should cross county lines. We have really pulled the leaders in each of the communities into a formal partnership.” — Interview with coalition leader

Conclusion

In summary, communicating about overdose prevention can be challenging, but not insurmountable. To guide your communications, remember that:

- A clear and specific overall strategy should shape the rest of your communications, not the other way around.

- Defining the audience with the power to make the change you seek will inform elements of your message strategy, like the frames you use, the values you evoke, the messengers you engage, and how you reach your target audience.

- You can respond to misinformation and difficult questions without repeating false claims.

We hope these recommendations on effective, strategic communications are a useful starting point for supporting life-saving tools and resources in your own community. As we heard again and again in interviews, communication is an ongoing process that helps build a foundation of partnerships and community support for overdose prevention strategies to keep our communities healthy, safe, and thriving.

Acknowledgments

This messaging guide was authored by Kim Garcia, MPH, and Pamela Mejia, MPH, MS. We would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions to the development of this guide: the NOPN team for their collaboration, resources, and connections to advocates in the field; the interviewees from across California for their time, expertise, and valuable insights; Aimee Hendle, Cindy Cipriani, and webinar participants for their review and feedback on sample messages; Heather Gehlert for her expertise in rural issues, media strategy, and web development; and Ingrid Daffner Krasnow for her expertise in rural issues and strategic communications.

Permission requests

If you are interested in copying or repurposing text or graphics from this messaging guide in an academic course or in other contexts, please email NOPN@healthleadership.org.

Appendix

Storytelling resources to reduce stigma

Our research revealed the importance of storytelling to reduce stigma and humanize substance use and overdose prevention. Here are some resources to build on how to use storytelling in your advocacy work and building on the storytelling skills of your community.

- Gone Too Soon: This poster memorial campaign by Sacramento County Opioid Coalition aimed to humanize the statistics by offering a look at the faces of community members who have been lost to opioids. The personal qualities shared invite us to glimpse into a part of their personality and what they liked to do (i.e. compassionate, musician)

- Addiction Language Guide: This resource by Shatterproof provides recommended language based on consensus, research, and expert opinion.

- Reducing Addiction Stigma: This fact sheet addresses the stigmas that exist regarding addiction, and learn how to reduce these stigmas in your community.

- Managing Pushback to Syringe Exchange: This video is a conversation with the Harm Reduction Coalition that highlights stigma reduction and explains how syringe exchanges are useful in getting those with opioid use disorder access to treatment.

Data and statistics to support your overall strategy

Some audiences may ask for evidence or data to better understand the problem. Here are some statistics to help strengthen your definition of the problem. For example, these can be especially helpful among audiences like government leaders or law enforcement who may benefit from seeing data to show how overdose prevention strategies can make communities safer.

Statistics about substance use

- One in seven Americans in their lifetime will have a substance use disorder (Fact Sheet)

- In the United States, drug overdoses have claimed over 932,000 lives over the past 21 years, and the drug overdose crisis continues to worsen. In 2020, the rate of drug overdose deaths accelerated and increased 31% from the year before. Synthetic opioids, such as illicitly manufactured fentanyl, continue to contribute to the majority of opioid-involved overdose deaths. (Preventing Opioid Overdose)

- Fentanyl’s increased presence in the drug supply is a key contributor to the increase in overdose deaths. Fentanyl can be up to 50 times stronger than heroin and up to 100 times stronger than morphine, so even small amounts of fentanyl can cause an overdose. Many illegal drugs, including counterfeit prescription opioid pills, heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, and ecstasy, can be mixed or laced with fentanyl with or without a person’s knowledge, as they would not be able to see, taste, or smell the fentanyl. (Fentanyl Facts)

Statistics about stigma

- Seven of the nine main drivers of substance use disorders are driven by stigma. (Campaigns find success in decreasing the stigma around substance abuse, which is greatest in rural communities)

- According to a study conducted by SAMHSA in 2014, more than 20 percent of people with substance use disorder did not seek treatment because they worried about the negative impact on their employment, and more than 17 percent were concerned about how their community would view them. The extent of misinformation about substance use disorders in public discussion—especially among healthcare providers, educators, policymakers, and media—reinforces barriers that prevent people from seeking help. (Rural Community Action Guide: Building Stronger Healthy, Drug-Free Rural Communities)

- 58% of Americans would like to see a lessening of stigma towards people with opioid addiction (Managing Pushback to Opioid Safety Strategies)

Resources for more evidence, data, and statistics

- COPN Measurement Guide: This measurement guide draws from on-the-ground work with an array of local overdose prevention coalitions affiliated with the Center for Health Leadership and Impact’s overdose prevention networks and is organized around the sequence in which coalitions need to work with data.

- Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program (ODMAP): ODMAP provides near real-time suspected overdose data across jurisdictions to support public safety and public health efforts to mobilize an immediate response to a sudden increase, or spike, in overdose events. ODMAP data can also be used to counter those who think substance use is “not my problem” by illustrating the scope of the problem in your own neighborhood or community.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)

- Data Resources on Overdose Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Resources for rural audiences

Strategies for working in rural communities

- Rural Community Action Guide: Building Stronger Healthy, Drug-Free Rural Communities by USDA: This guide shares insights and expertise from a wide range of stakeholders working to address substance use disorder and related issues in rural communities nationwide. Learn about recommended action steps rural communities can take related to prevention, treatment, and recovery.

- Rural Community Action Guide: Promising Practices Supplement: Discover rural programs and activities underway to address these issues that can be adapted in other rural communities.

- Building sustainable rural substance use disorder partnerships: This article provides key strategies on how to create sustainable coalitions in rural settings.

- Exploring Urban-Rural Disparities in Accessing Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder by American Institutes for Research: People living with opioid use disorder in rural communities often face barriers to accessing MAT.

Examples of success from rural communities

- Example from the Field: How a Rural County Implemented Harm Reduction Strategies: Video shows how a rural coalition successfully implemented harm reduction strategies

- Wider access to Narcan helps rural communities fight overdose deaths: The FDA recently made it easier for people to obtain a powerful overdose-reversing medicine. Narcan previously required a prescription, but soon will be sold over the counter. Communities are already using it to fight overdose deaths.

- “Where They’re At”—Harm Reduction in Rural America: Read this compelling story of harm reduction programs in rural America and how removing these programs is creating the bigger problem of deaths due to overdose.

- Campaigns find success in decreasing the stigma around substance abuse, which is greatest in rural communities: This article details successful campaigns for decreasing the stigma around substance abuse, which is greatest in rural communities.

- Decreasing Substance Abuse Stigma in Rural Communities: An article on how reducing the stigma surrounding substance-use disorders can help change beliefs and support harm reduction strategies.

- Bridging urban/rural responses to opioid use/ overdose: This video shows how programs to reduce harm from opioid use have historically been implemented in cities, and how those programs have been effectively translated into other communities. The speaker also shares findings from ethnographic research with people who use opioids in rural and remote regions of California about what programs and services they would like to see in their communities.

- For One Rural Community, Fighting Addiction Started With Recruiting The Right Doctor: This article from NPR focuses on the barriers of finding treatment services in rural communities and how NorthLakes Community Clinic, which serves Medicaid and Medicare patients, expanded its addiction recovery program with the help of state and federal grants targeting opioid use. Central to their plan was a physician champion who could lead the new program.