Introduction

Is there more violent crime in the United States than there was a year ago? Less? What about in your local area? A 2023 survey from Gallup found that Americans are confused about these questions, and perceptions of violent crime often do not align with the data.1 And that’s just when it comes to the big picture. Add in nuances around violence involving firearms, and misunderstandings soar. For example, many people across the political spectrum are unaware that more than half of firearm deaths in the U.S. are suicides.2

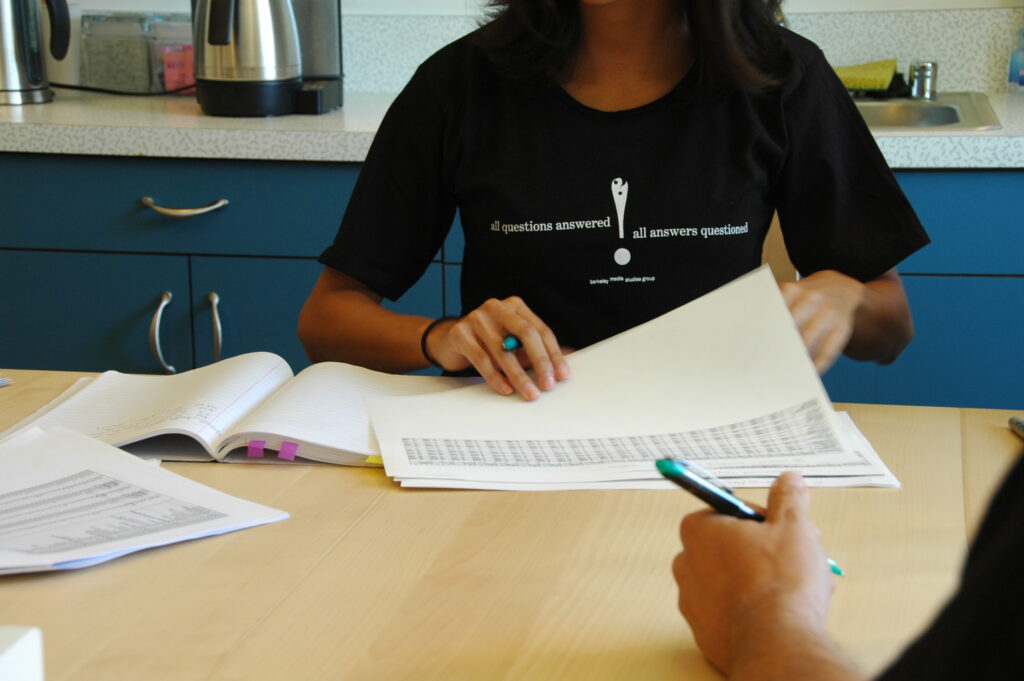

In 2024, the U.S. Surgeon General declared injury and death from firearms a public health crisis, which highlighted the critical and ongoing need for solutions to the crisis grounded in principles of community action and systems change. California advocates are already at the forefront of leading community-organizing efforts to move the needle on firearm injury and death, using a range of interventions from school-based and restorative practices to trauma-responsive care to cognitive behavioral therapy. This guide is intended for advocates; it aims to give them a roadmap for using the news to lift up those solutions and amplify messages from the communities most affected by the problem, so that the narrative around efforts to prevent firearm injury and death is as robust as prevention, intervention, and healing work happening around the state.

News coverage matters because it not only affects the public’s knowledge about violence and its causes, but also shapes how audiences understand potential solutions.3,4,5 Right now, stories about community-led efforts to prevent firearm-related injuries and deaths aren’t the ones we see and hear the most frequently. Instead, news about firearm deaths and injuries tends to focus squarely on mass shootings. Mass shootings are undoubtedly tragic — and on the rise — but comprise only a small fraction of firearm-involved deaths and injuries in this country.

When the news does spotlight day-to-day incidents involving firearms, mainstream outlets often struggle to tell stories about the causes of and solutions to firearm violence and firearm suicide in ways that can help readers and viewers understand larger patterns and truths about what it takes to make communities safer. Instead, news stories often focus on street-level assaults and homicides, and overrepresent Black and Brown communities as perpetrators of violence. News about firearms also tends to prioritize the perspectives of law enforcement, while the voices of people most directly impacted by violence or firearm suicide are largely absent, as are discussions of community-led solutions.

From decades of research, including our own, we know that these patterns may keep audiences from understanding the true prevalence of issues like firearm suicide and domestic violence involving firearms in their communities; deflect attention from systemic and structural inequities like racism and poverty; reinforce the underrepresentation of Black and Brown communities as expert voices and leaders of change; and obscure the possibility of approaches to preventing violence and promoting healing that go beyond criminal justice responses.6 What’s more, the news shapes policy agendas.7,8,9 So, when community-led efforts to reduce injury and death from firearms aren’t part of the public conversation, it’s harder for the people leading those efforts to ensure that voters, funders, potential community partners, and others are aware of and engaged in their work.

On the other hand, when community members and spokespeople from community-led efforts are the key sources for news stories — not just reacting to, but creating news proactively — then they can broaden the understanding of firearm violence prevention by expanding who speaks about it and what they say. Community members can, for example:

- challenge harmful stereotypes or narratives about their communities;

- draw attention to equity and justice concerns relating to policing;

- point out that community-led violence prevention advocates report that they are often held to higher standards than law enforcement when it comes to reporting positive outcomes; or

- call on the media to investigate community-based solutions with the same intensity and focus with which they investigate problems.

How, then, can people working to prevent injury and death from firearms create effective messaging? How can they communicate such complex issues when many different stories emerge from the data? For instance, while California has the strongest laws in the country and a lower rate of deaths due to firearms per capita than most states, firearm deaths have dramatically increased in the last few years, mirroring national trends.

That’s precisely what we hope this guide will do. Advocates can use it to help shape news narratives to reflect an important truth: that no matter who we are or where we live, we all want to reduce the public health problem of injury and death from firearms — and everyone can play a role in keeping people safe.

With support from this guide, California advocates can engage in media advocacy: the strategic use of mass media to communicate with policymakers, thought leaders, and the voting public about efforts to prevent injury and death from firearms, support people affected by violence, and promote healing.10 We hope the tactics outlined here will help advocates to better align their organizing and messaging efforts so that policies and programs to reduce violence and promote healing — as well as the narrative surrounding them — reinforce one another. That’s a key step toward helping move us faster and further toward a world in which safety is the norm.

Who is this guide for?

This guide is for advocates who are working to help reduce injuries and deaths from firearms in their community and want to become better, more confident communicators on the subject. Because this issue affects people from many different walks of life, we hope it is equally useful to advocates from varying backgrounds. Maybe you are a veteran, and your primary concern is about firearm suicide. Perhaps you are a responsible gun owner whose main goal is to support local efforts to keep your loved ones safe. Maybe you have never handled a firearm, but you have seen the ripple effect of trauma that results when they are misused. You might engage in advocacy as a researcher or simply as a concerned community member who is becoming more active in this work. Your neighborhood could be urban or rural, racially homogenous or ethnically diverse. Further, you might be focused on a very specific issue area, like domestic violence, self-harm, or community violence.

We aimed to create a resource that is flexible enough to address communication challenges that span location and demographics — and that you can refine and tailor to your community and needs because you are the expert on your own background and experience, and know the challenges and needs in your own community. As you read this guide, think of it as a foundation — one that will equip you with research-based lessons and communication guidance that you can adapt based on your local context and specific social change goals. Using this foundation, you will be able to create messages and media pitches that help to advance those goals. You will also be able to anticipate roadblocks and plan ways around them.

Still wondering? Frequently asked questions — and answers to help you decide

Here are some frequently asked questions that might help you decide if this is the right resource for you:

Q: I’m an organizer — why do I need the news media?

One of the main ways people come to understand the world around them, apart from direct experience, is through the media. It shapes what people know — and, critically, what they don’t know — about social issues like deaths and injuries involving firearms. How journalists report on issues affects what solutions people support and whether they even believe that change is possible. Media, then, create the tides that organizers and advocates must swim in. The Surgeon General’s announcement framing firearm injury and death as public health crises could be an important moment to build a groundswell of support for innovative, community-led solutions — but it will take work to maintain that energy and attention.

If media narratives run counter to your goals, then your job as an organizer will be much more difficult. That’s why it’s important to know not only how the news is characterizing death and injury from firearms, but also how you can make sure that your community’s perspectives are part of the conversation. If the people most affected by an issue don’t see their own voices and concerns reflected back to them in media coverage, then instead of feeling inspired to act, they may feel isolated and take fewer actions or disengage altogether.

To help shape media narratives in ways that elevate community voices, advocates can engage in a practice known as media advocacy, which means leveraging the media strategically to shape how both the public and decision-makers understand an issue and the goal you are trying to achieve, whether it’s passing a policy, implementing a program, or something else. Advocates and organizers can do this through writing opinion pieces, blogging, pitching story ideas to journalists, becoming a go-to source for reporters, etc. For more about the media and why it matters, see our section on media framing and why it matters.

Q: Will this guide tell me what to say?

Yes and no. Firearm-involved deaths and injuries in all their forms are deeply entrenched issues with complex causes. As such, there are no magic words that can move audiences to agree with or support your proposed solutions. However, there are patterns and communication pitfalls that we know from 30 years of analyzing news coverage of this issue, and this guide will provide you with a framework and sample messages that you can modify and use to develop your own stories and talking points. Because the reality of violence is nuanced, we cannot take a paint-by-numbers approach to communicating about it. We will help you refine your technique, but you will still be in control of how you color the canvas. As a starting point, check out the section on developing your overall strategy — the framework that you’ll be refining.

Q: I have to get ready for an interview and I'm worried about the questions they're going to ask — how should I prepare?

The best way to prepare for difficult questions is to anticipate them. We recommend asking reporters to send you a list of the questions they plan to ask. If they say no, brainstorm a list of common questions as well as the ones that you dread being asked. Once you’ve done that, draft your answers using what you’ve learned about framing in this guide and practice, practice, practice. The more you practice, the more “muscle memory” you will build, and the more confident you will be. This does not mean that you have to answer every question you receive. In the message development section of this guide, we’ll share examples of how you can pivot to a different angle if a conversation gets too far off track. And don’t be afraid to repeat your main message or messages again and again since reporters will likely pick and choose what they use during the editing process. As you gain experience, you’ll see that you don’t need to have all the answers to still create momentum toward your policy or organizing goals. For more detailed advice, review When — and how — will you use the news?

Q: There are so many points I want to make, but I know my news interview will be brief; how should I handle this?

As we often say at BMSG, you can’t be strategic and comprehensive at the same time. You have to prioritize. Before the interview, identify the main points you want to make. Other themes will have to wait, and that’s OK. Today’s news environment is crowded with more choices in content and platforms than ever before, which means that having a single, clear message is critical to breaking through that noise. No individual story can encapsulate all of your organizing aims and hold your audience’s attention. What you can’t mention in one interview could become the highlight of a future conversation. Narrative change, like other forms of change, is incremental.

Q: How do I make sure the audience responds positively to my message?

No matter how carefully you craft and deliver your message, not every reader or audience member will receive or respond to it in the same way. Different people can and will perceive the exact same information differently; that’s because no one is a blank slate. We all come to information with ideas already in our minds about how the world works — ideas that are based on our culture, upbringing, media environment, and other factors. Your job as a communicator is not to ensure that everyone agrees with you — strive for progress, not perfection. When you are delivering a message, imagine you are communicating with someone who is already interested and receptive, even if their views are unlike your own. People whose views are radically different and who are staunchly opposed to your ideas are not your target audience.

Q: What about unintentional shootings?

Preventing unintentional shootings is an important public safety consideration; however, they are beyond the scope of this guide.

Q: I’m worried about alienating firearm owners in my community — what should I do?

It’s tempting to avoid the things that make us nervous. Resist that urge. Although you may worry about your word choices or framing your messages in a way that won’t resonate with firearm owners, the only way to create messages that are more inclusive is to have difficult conversations. When talking with firearm owners, approach them with openness and curiosity. Coming to the table in the spirit of learning will keep the conversation from becoming transactional or forced. Most people want to feel seen and understood, and that happens when we listen without judgment and seek to understand rather than persuade.

Q: What about police or state-sanctioned violence involving firearms?

Violence at the hands of law enforcement is an important component of community violence, and we hope to continue studying the narrative that surrounds it; however, it is beyond the scope of this guide. We urge users of this guide to explore resources from others with deep expertise in this field like the Anti-Police Terror Project.

Q: What if I do everything "right" in a media interview, and the journalist still misses the most important points?

Narrative change happens over the long term across many interviews and stories. It is important not to expect too much from any one interaction with a journalist. Additionally, the final article or broadcast is not the only metric that matters. If, for example, a reporter doesn’t include a particular quote or perspective, their conversation with you still will have helped to educate them and introduce them to angles they can explore in future reporting. What happens behind the scenes still counts as progress if it is helping to move the needle forward.

The same can also be true of failure. The early days of tobacco control offered a lesson in this: It took decades for public health advocates to pass policies to put warnings on cigarette packs and ads, remove cigarette vending machines, ensure smoke-free air in public spaces, and institute tobacco taxes. Each failed effort, BMSG Director Lori Dorfman has written, was like dropping a pebble into a river. At first, it slips beneath the surface and seems to have had no impact. But advocates kept throwing pebbles into the water, and the result is a bridge that we can now walk across. It’s not uncommon for yesterday’s controversies to become tomorrow’s common sense, as has been the case with many health efforts, from seatbelts to soda taxes. That shift happens when people keep conversations going: The more an idea gets proposed and discussed, the more people get used to it and start to understand it. That momentum also encourages supporters of a proposed solution to be more visible and vocal. So, again, take the long view with your media advocacy efforts, and remember that each story is part of a much larger, and changing, narrative landscape.

If this feels like the right resource for you, let’s get started.

Using this guide to craft messages and communication

We’ve designed the guide so that you can read its sections in any order, picking out what’s most useful to you. We hope it allows you to:

- Focus on one goal at a time. Addressing a problem this big demands investments in time, energy, and resources that can take a very long time. This guide is designed to support advocates and organizers working to advance a variety of smaller, incremental changes at the community level, as well as bigger overall objectives.

- Frame prevention, intervention, and healing in the context of racial equity and community-led action in messaging and communication.

- Focus on using the news to reach decision-makers (that is, anyone who has the power to create change in institutions, systems, and communities), as well as those who can influence them.

People are inundated with messages about firearms every day. As with many issue areas, audiences can be resistant to messages and ideas they aren’t familiar with. In other words, you may have to repeat yourself, or reframe problematic messages and repeat the reframes!

However, our hope is that, combined with training and practice, this guide will help community groups develop strategies and practices to make stories about community-led success the norm rather than the exception.

A few other things to keep in mind

If this is the guide for you, keep a few core assumptions in mind as you use it.

Across topic areas, advocates face shared communication challenges.

People “walk through many doors” to get to the shared goal of reducing injury and death from firearms: Some focus on preventing domestic violence involving firearms, others on reducing acts of community violence involving firearms, and still others on preventing firearm suicide. Each of these issue areas is very different, with its own terminology, experts, champions, detractors, and policy levers. During the course of our research we did find, however, that these three areas share framing and communication challenges that are, at their core, similar. Specifically, people struggle with challenges like helping audiences overcome feelings of futility and fatalism about the possibility of change; naming and centering racial equity in their work; and identifying and supporting credible and authentic messengers. Much of this guide centers on how to address those shared, foundational challenges. However, whenever possible, we break out examples and recommendations that are specific to a given topic area so you can find the information most relevant to your work.

Messages should come from the people who know the problem — and solution — best.

We at BMSG are not experts in all the nuances of addressing firearm injury and death, but we are experts in developing communication strategies to help build support for large-scale changes that improve public health and well-being. For this guide, we applied that expertise to the information gathered through dialogues and deep listening with experts in this field. Because effective proposed solutions — and the messages that support them — need to be developed and carried out by the people closest to the problem, our hope is that readers will apply the information in this guide to their own local context and use it to help change the systems and conditions in their own communities to reduce death and injury from firearms.

Racial equity is foundational.

Racial equity must be the framework that guides conversations about reducing firearm homicides and injuries because, to quote one expert we spoke with, “safety is not distributed equally.” Not only are communities of color more impacted by firearm violence (and, increasingly, firearm suicide), they have also been harmed by policies ostensibly designed to keep communities safer.11,12

It is critical, then, for organizations working to reduce firearm homicides and injuries to center solutions and work led by people of color and for the media to lift up that work. Doing so is both the right thing to do and the most effective. The past has shown us that when we fail to name structural racism and when those who are removed from the issue try to lead from the outside, progress stalls. Historically, white violence prevention advocates have had the loudest voices at the decision-making table, with policy and systems change responses often arising in the aftermath of public mass shootings when white and affluent communities are affected or feel threatened.13 Additionally, media narratives about violence have often distorted the role of race and perpetuated stereotypes, with white victims and survivors receiving more resources, attention, and nuanced coverage than Black and Brown victims and survivors.14,15

Firearm owners — and their families — must be part of the conversation about safety.

This guide is based on the assumption that many of the people who use it — and many of the people who receive the messages that emerge from it — are themselves firearm owners. People own or purchase firearms for a variety of reasons and firearms ownership is prevalent nationally in the U.S., significantly increasing over the last ten years.16,17,18 Additionally, many firearm owners are members of BIPOC communities and are increasingly female: In interviews for this research, for example, we heard from BIPOC community members who are arming themselves because they cannot trust law enforcement or other institutions to protect them.

The range of firearm owners we spoke to and polled sometimes reported feeling left out of conversations about preventing death and injury. This lack of inclusion may help explain why many important efforts to engage everyone in reducing injury and death from firearms have failed to gain traction. Throughout this guide, we incorporate learnings and guidance from the many firearm owners and family members of firearm owners who helped inform this work and have generously shared their time and expertise with us. Where necessary, we also explicitly name unique considerations, questions, or points of tension that should be considered in communication with firearm owners specifically.

A word about language ….

We have some specific terms we use — and avoid — in talking about reducing injury and death from firearms.

| Term or terms we use | What they mean, and why we use them |

|---|---|

| Firearm | We use the term “firearm” rather than “gun” whenever possible because that’s a term that many people we spoke with, including firearm owners, prefer. As one respondent noted, “there are many kinds of guns — water guns, paint guns, but the term 'firearm' is more precise.” |

| Community firearm violence or community violence involving firearms | This term refers to assaults or homicides involving firearms that happen in public settings. “Community violence” is a term that many advocates in the field have adopted to shift narratives away from potentially stigmatizing terms like “street violence,” “youth violence,” or “gang violence.” |

| Domestic violence or intimate partner violence involving firearms | We are using this term to refer to intimate partner and family violence. Over half of all intimate partner homicides are committed with firearms, and over two thirds of mass shootings have a connection to domestic violence.19 It’s important to keep in mind that firearms in domestic violence situations not only contribute to death and serious physical injuries but are also used to control partners and family members. |

| Firearm suicide | As referenced above we use “firearm” suicide and not “gun” suicide as firearm owners prefer to use this term. Firearms are the form of suicide attempt most likely to end in death: studies show that 9 in 10 individuals who attempt suicide with a firearm will die.20 |

| “People with felony convictions,” “people who cause harm,” “people accused of violence” and other person-first terms | Person-first language focuses on describing people, rather than labeling them — in other words, person-first language is about conduct, not character. Using person-first language is important for two reasons: 1)To talk about preventing violence or supporting survivors, we must talk about the people who carry out these acts. But the beliefs that many people hold about the individuals who commit violence can make it hard to talk effectively about prevention: Terms like “offenders,” “abusers,” or “perpetrators” can make audiences see people who cause harm as distant or “other.” It also reduces people to their worst action — instead of recognizing that they are people who have caused harm and who may have experienced harm as well. 2) If we see firearm violence as something that only “bad people” could possibly do, it makes it harder to see and talk about solutions that go beyond incarceration and punishment to address prevention, healing, and community connectedness. We also know that conversations about firearms are highly racialized, with many audiences unfairly and inaccurately assuming that people of color are responsible for causing harm. Terms like “offenders,” “perpetrators,” “felons”, “convicts,” or other terms may activate racist and harmful stereotypes for some audiences — so we avoid them. For these reasons, we model person-first language in this guide, giving examples of what it can look like in practice. |

How we wrote this guide

BMSG’s process for understanding and reframing narratives is iterative and grounded in our expertise in the field. For this project, we built upon what we have learned working with communities and studying media narratives over 30 years and gathered data in multiple ways, including through media analyses, systematic reviews of advocacy materials and existing public opinion polling, and interviews and listening sessions designed to center the experiences of those who are most deeply involved in prevention work. Any unattributed quotations in this guide come from those interviews or from conversations we had at meetings and conferences; they are unattributed to protect the anonymity of participants.

An important part of our research included message testing. We partnered with Lake Research Partners (LRP), a polling firm with deep experience in and knowledge of messaging around firearms and firearm policies, to develop and test messages about community-led approaches to preventing injury and death from firearms.

To learn more about what we did, see our methods.

A word from our funders

In the wake of the tragic mass shooting in San Bernardino in 2015, community leaders and funders across California came together to recognize the urgent need for a collective response to the growing firearm violence epidemic. From these efforts, the Hope and Heal Fund emerged as the first and only fund solely dedicated to reducing firearm injuries and trauma in California.

Since its launch in December 2016, the Hope and Heal Fund has invested over $7 million in identifying, supporting, and scaling best practices and strategic solutions to reduce all forms of firearm injuries, including suicide, domestic violence, and community violence. Our mission is to lift up and support local community efforts to reduce violence and push innovative strategies with a systems change approach, ensuring our systems are more equitable and responsive to addressing firearm violence and suicide.

Since 2017, our collaboration with Berkeley Media Studies Group has focused on transforming the media narrative around firearm violence and suicide, ensuring that communities receive authentic, resonant messages that highlight and support local solutions.

Through this partnership, we have taken significant steps to understand and influence public narratives around firearm violence by evaluating news coverage, conducting deep listening sessions with community leaders, overseeing public opinion polling, and synthesizing our findings into actionable strategies.

That collaboration led to the message guide you’re reading now. Our goal is to enhance the media skills and increase the capacity of community leaders, so they can effectively tell their own stories and highlight the unique solutions that work in their communities. As you engage with this resource, we invite you to see it as part of a broader vision for a safer, healthier California — one where all communities have the tools they need to prevent firearm violence before it starts.

This guide is a reflection of our commitment to collaboration, innovation, and narrative change in the fight to end firearm violence, and we are honored to partner with BMSG in this critical work.

How does the news frame messages about firearms?

An important step for effective communication is understanding the context in which they are received: Messages about firearms are never shared in a vacuum. Their meaning comes not only from what the sender intends but also from how the receiver integrates the new information with what they already know and believe. It’s helpful, then, to understand the background against which audiences form their opinions about firearms and what to do about them. This section of the guide explains how audiences’ existing knowledge come together with the information environment (like news coverage) to influence how they interpret messages about firearms and firearm access. With this in mind, you can anticipate potential roadblocks, plan for how to correct misinformation, and identify strategic communication opportunities.

What do people believe about firearms?

There are no blank slates when it comes to communicating about firearms. The ideas that people already hold in their minds affect how they perceive efforts to prevent or address injury and death from firearms. It only takes a few cues, like a word or a phrase, to activate preconceived — and often unconscious — notions about an issue. For example, consider terms like “firearm safety” or “gun safety.” What ideas do these terms activate for you? Some people might think about legislation, policies, and programs that government and community actors should lead — a mindset about shared accountability. For others, like many of the firearm owners we worked with, it might spur thoughts about personal responsibility, like individual actions to safely store and use firearms.

Many groups have studied the beliefs and values that people hold that help them understand firearms and access to firearms. Broadly, research shows that:

- Americans are deeply concerned about violence involving firearms, and particularly about mass shootings.21,22,23

- Americans are divided in their opinions about whether firearms keep people safer or make them more vulnerable.23,24

- Many people support solutions that can prevent injury and death from firearms. However, people are deeply divided in their thinking about federal firearm legislation, with many believing that federal policy efforts are ineffective at best.23,24

- Although no group is a monolith, audiences do tend to report differing opinions based on various demographic and social factors such as race, gender, firearm ownership status, political affiliation, or level of education. For example, beliefs about the lethality of firearms are also closely tied to where a person lives: Our research in California with Lake Research Partners shows that people in rural areas are less likely to believe that the presence of — and access to — firearms highly increase the risk of death in domestic violence incidents or suicide attempts.

Additionally, Americans understand different kinds of violence and harm involving firearms in markedly different ways:

Firearms and community violence: Research on community violence has focused on “gang violence,” youth-related crime, and the criminal justice system — and indeed, in our research with Lake Research Partners, respondents regularly associated firearms with gang violence. Media depictions of boys and men of color are distorted and paint them as criminals,25 bolstering public support for punitive solutions.26 However, over time, public opinion has shifted toward rehabilitation, prevention, and reintegration within the criminal justice system.

Firearms and domestic violence: Our research with Lake Research Partners revealed that many people in California are unaware of the true magnitude of domestic violence involving firearms — 4 out of 10 people polled, for example, incorrectly believed firearms were only rarely or never used in domestic violence situations. However, when people are aware of the connections between domestic violence and firearms, research shows very high levels of support among the general public and firearm owners for policies to remove firearms from those accused or convicted of domestic violence.27 However, these views vary across gender: Women may see firearm removal in the context of domestic violence as a way to prevent any further harm, while men view it as punishment for using firearms inappropriately.28

Firearms and suicide: The relationship between access to firearms and suicide has historically been poorly understood, despite ample data connecting the two.2,29,30 Most people see suicide as a matter of individual behavior, unconnected to firearm access:31,32,33 Our research with Lake Research Partners, for example, found that respondents regularly associated the term “firearm suicide” with mental health.

The way we discuss firearms and related violence shapes how audiences understand the problem and what to do about it. Communication problems can arise when the messages we develop don’t take into account our audience’s thoughts and experiences.

One of the most deeply rooted mindsets, or ideologies, in American society is individualism, which emphasizes personal choices and resolve. The idea is that if you work hard, you will succeed, and conversely if you fail, it’s your own fault.34 For most people, individualism is the starting point for any conversation about how to solve a problem. If no alternative is offered, many people’s minds will go there first. Rugged individualism is so deeply ingrained in dominant culture that often people will focus only on personal choices and failings — and ignore how systems, institutions, or social norms affect what happens — even when they see evidence that there might be other factors to consider.34

Conversations about firearms often reinforce this individualistic ideology in part because firearms themselves are so closely tied to ideas about self-protection, self-reliance, and what it means to be an American. To quote one prevention expert we spoke with, “There’s a mythology around firearms — that has grown from the marketing — about this mythical white man who is the sort of creator of the country, the pioneer spirit.”

When it comes to firearms, the focus on individuals often prevents people from being able to envision what communities or institutions can and should do to be part of solving the problem. Additionally, important pieces of context — like structural racism and the extent to which safety is not distributed equally — are less visible and, therefore, harder to name and address. As one interviewee observed, most current conversations about firearms don't illustrate that related patterns in injury and death have “been passed down from enslavement and colonization,” obscuring “the historical ways that [violence] has been passed down to us.”

What are news (or story) frames?

One of the reasons we’re interested in understanding dominant cultural beliefs surrounding firearms is because they influence how people interpret news coverage. At the same time, news coverage shapes people’s perspectives on firearms.

Journalists’ decisions about what issues to cover and how to portray or frame them affect the public’s understanding of the world around us. Thorough reporting can raise the profile of an issue like firearms, while problems not covered by the news media are often neglected and remain largely outside public discourse and policy debate.7,8,9 News frames also influence whose perspectives are seen as credible and valuable, and which solutions are elevated or ignored.3,4

We typically observe two types of framing in news coverage, sometimes on their own but often together.35,36

Portrait framing (sometimes called “episodic framing”) centers on an individual person or a particular incident of violence. Portrait stories reinforce the default frame, which holds individuals responsible both for creating the problem and solving it. This approach makes it harder for audiences to see and imagine broader, systemic solutions that can make everyone safer. It can also make violence feel inevitable since portrait stories typically don’t include language about solutions. Most news stories are portrait frames.

Landscape framing (sometimes called “thematic framing”), on the other hand, illustrates the broader context (or “landscape”) in which individual incidents occur. Landscape stories can help audiences see the systems and structures that increase the risks of firearm injuries and deaths, along with system-level interventions that could prevent or reduce harm. Stories that include people but also bring the landscape into view help expand the conversation about who is responsible for causing — and solving — problems. Stories that embed portraits within wider landscapes help shift an audience’s focus solely from personal culpability to bigger questions about community, institutional, and government accountability.

What are news frames about firearms?

When we look at frames in news coverage, we can learn what the public might know or not know about firearms and firearm-related injuries and deaths, particularly if the news is their main source of information. News framing can be particularly powerful when it comes to issues related to firearms,37,38,39 in part because research shows that the more media depicting violence a person consumes, the more likely they are to believe the world to be a dangerous place, react from fear, and support punitive policies.40 According to one interviewee, news about firearms acts like a “background feeder telling us it's dangerous out there.”

If all people knew about firearm injuries and deaths came from the news, what would they know? And, perhaps more importantly, what would they NOT know?

As part of the process of developing this guide, BMSG explored how community violence involving firearms, domestic violence involving firearms, and firearm suicide were framed in California news coverage. Our first analysis explored the content of California print news and photographs from 2017. Our second report focused on the volume of print news published in California from 2020-2021. In addition, this second analysis explored how firearm injuries and deaths caused by police — a key element to be considered in any conversation about violence for many communities — appeared in the news.41

Patterns across all news about firearms

Overall, our analyses showed that across issues:

- News was driven by distinct incidents (“portrait framing”). Stories focused narrowly on isolated, high-profile incidents of crime and violence and frequently highlighted the emotional and physical impacts on individual victims and their families.

- The criminal justice system dominated the news in the sources quoted. Stories relied on quotes from police and other representatives of the criminal justice system.

- Solutions — including community-led solutions — were absent. The emphasis on individual incidents made it harder to show what schools, faith communities, businesses, advocates, and community groups were doing to prevent injury and deaths from firearms. When they appeared, solutions, and responsibility for putting them in place, were frequently situated within the criminal justice system, such as arrests, trials, or police investigations.

Patterns in news about community firearm violence

- Community-level violence and police shootings dominated the coverage of firearm violence, and coverage increased over time.

- Stories about community violence occasionally quoted people with lived experience, like victims of firearm injuries and family and friends of victims.

- Many stories about community violence involving firearms included language that framed people involved in violence as menacing, threatening, or beyond help — a typical article called people accused of community violence with firearms “criminals and crazies.”42

- An analysis of photos that accompany news stories showed that people of color, particularly men, were overwhelmingly portrayed as perpetrators of community violence. In contrast, white individuals, primarily male-identified people, appeared in photos often as police or other representatives of the criminal justice system.

Patterns in news about domestic violence involving firearms

- Stories about domestic violence involving firearms didn't appear as often as stories about community violence, though the coverage did increase over time.

- Stories about domestic violence involving firearms were unique in that advocacy group members, mental health professionals, and researchers were quoted to expand the frame to provide additional context.

- Coverage emphasized individual choices in stories about domestic violence by reinforcing blame and stigma of victims or casting doubt on survivors’ stories.

- In news about domestic violence and firearms, all photos of alleged perpetrators were men, and the majority were men of color. Most victims of domestic abuse whose photos appeared in the news were female, and half of the victims pictured were women of color.

Patterns in news about firearm suicide

- Stories about firearm suicide appeared far less frequently than coverage of any other issue we studied, though the overall amount of coverage did increase over time.

- Stories about firearm suicide were more likely than stories about other issues to “expand the frame” to describe contextual factors, such as income inequality or limited access to mental health care.

- Stories about firearm suicide more often included quotes from researchers or mental health providers than did stories about other issues we studied.

Although there are well-documented recommendations for reporting on suicide that advise against sharing graphic details about the incident, our analysis showed that fully one-fifth of articles about suicide included extremely explicit details about the circumstances of the death.

Your turn:

Identifying frames

What are some of the dominant news frames around firearms — and harm from firearms — in your community?

How can we reframe?

Reporters are always looking for a compelling story, and those often start with a portrait frame. Advocates want to provide compelling messages about community-led work that tells a story while expanding the frame to include the landscape that holds that story's outcome.

Shifting deeply entrenched ideologies, particularly about an issue as politically fraught and personally meaningful as firearms, is challenging. Fortunately, framing techniques can help. We can leverage them by:

- Grounding our communication work in overall strategies focused on changing systems rather than on punishing people, and centering communities too often left out of the frame.

- “Pulling back the lens” to show the landscape in which violence occurs, the community-led solutions that are possible, and the values that ground prevention, treatment, and healing efforts.

- Expanding the media narrative by pitching articles and telling stories about issues that are too often left out, like prevention efforts, healing, and community innovation.

- Developing and delivering messages that keep the focus on community-led efforts to prevent violence, support survivors, promote healing, and center the people closest to the the problems, and the solutions.

- Bringing new voices to the foreground of the media conversation, and ensuring they have the support they need to speak — and keep speaking — as leaders, agents of change, and experts.

In summary

There are no blank slates when it comes to firearms. Americans have many deeply held beliefs, some of them contradictory, and many rooted in rugged individualism and personal responsibility. These mindsets can make it harder to see the promise of community-led solutions, or to explore the realities of systemic racial inequities, since they focus so narrowly on individual behavior change and culpability.

Most stories about firearms are framed like portraits that reinforce disconnection from systems and communities by focusing on the details of specific incidents of injury and death from firearms. Fortunately, there are many ways to expand media frames to illustrate the landscape in which violence and suicide occur, center community action around prevention and healing, and center racial equity.

What’s the change you want to make?

Communicating effectively helps us get where we want to go. But you can’t figure out what you are going to say until you decide what you want to do. Language is important, but it’s not first. Messaging is never first: it flows from the specific policies, cultural shifts, or programs you want to see, not the other way around.

To be persuasive, messages must be rooted in the change you’re seeking — and communicated against the backdrop of the world around us. For example, when it comes to talking about strategies to reduce injury and death from firearms, you may find yourself being asked to assuage doubts about a recent incident of violence. That might change the words you use or how you respond to questions from a reporter or a funder, but it likely won’t change your overall strategy for the change you want to see in your community.

BMSG's tried-and-true approach is to use the Layers of Strategy, which helps advocates think through the components of a communications strategy. To develop your overall strategy, determine:

- What is the problem you want to solve, and how do you want to solve it?

- Who has the power to make that change and what should they do?

- Who can you mobilize to exert pressure and advocate for your cause? What’s the next step they can take to be part of the solution?

The answers to these questions will determine not only what actions you take, but also how you communicate about them.

What is the problem you want to solve, and how do you want to solve it?

If you are reading this guide, you almost certainly want to prevent violence, but naming “violence prevention” as your aim is too broad. The more specific your goal is, the better.

Sometimes when people hear the words “communication” or “media,” the first thing they think about is raising awareness about their issue. That’s understandable, especially since when it comes to firearms, many people aren’t aware of how common certain kinds of death and injury are. Our work with Lake Research Partners, for example, showed that many Californians are surprised by the frequency with which firearms are used in suicide or in incidents of domestic violence. But what happens once your audience is more aware of the problem? What do you want them to do with that information?

To develop your strategy, consider:

- What type of firearm injuries or harm are you focused on?

- What are the root causes or context for those forms of injuries or harm ?

- Are there examples of where and how your proposed solution has been successful?

- How does your solution benefit people who have been directly harmed — and how could it benefit people who haven’t been directly impacted by firearm violence or suicide?

These kinds of questions are key to engaging your audience (be it community residents, funders, opinion leaders, members of a school board, etc.) in a specific solution or set of solutions and driving real, sustained change.

Promising practices that can help ground overall strategy

The good news is that people are hungry for solutions that go beyond legislation or increasing police responses. We’ve worked with colleagues and experts to identify and explore community-led work happening around California. In the process, we realized that, although different communities are pursuing various areas of work tailored to their unique contexts and needs, many strategies are rooted in shared core approaches — what we call “promising practices” — because, as one expert noted, there “isn’t one magic solution for safety.” Among the solutions communities are pursuing to reduce injury and death in California are:

Collecting and sharing highly localized data.

Many of the experts we spoke with pointed out the flaws in existing data sets, which may provide only information about, for example, injuries, fatalities, or protective factors at a county, state, or regional level. Such high-level or combined data may not provide the nuance that advocates need to assess hyper-local trends in domestic violence, community violence, or firearm suicide, and make the case for community-specific solutions. Furthermore, in many communities, law enforcement controls and limits access to firearm violence data, and they use their data to control a narrative to muster support for funding their own efforts. It is critical for communities to have full access to all data so they can tell the stories of their own communities and be able to protect the data they collect to ensure the safety of the communities they serve. Ultimately, experts agreed that “local data collection lets people tell their own stories,” as when:

- Community violence intervention leaders call for hyperlocal data collection about firearm homicides and assaults to tailor interventions.

- Firearm suicide preventionists advocate for an asset map of voluntary firearm safe storage sites in their community for those in crisis.

- Advocates for domestic violence survivors push for accurate disaggregated data showing the prevalence of DV-related firearm homicides in a community (compared to other firearm homicides).

Building and tailoring sustained support for those most at risk of harm.

People spoke again and again about the need to center the experiences of those “closest to the pain” — in other words, most familiar with the problem and with solutions that work. Of course, centering those most affected looks different in different contexts, as when:

- Community violence intervention leaders focus on engaging people who have been shot to reduce future violence and promote healing;

- Firearm suicide preventionists work with the families, friends, and loved ones of firearm owners to increase knowledge of safe storage options;

- Advocates for domestic violence survivors train survivors to talk about firearm access, related risks, and what might have helped them navigate challenges effectively.

Investing in existing community leadership and relationships.

We found that local efforts are often grounded in the belief that those in the community are best positioned to provide support and engagement. As one respondent with decades of experience in domestic and family violence prevention reflected, “If in communities, we were able to create deep relationships, if I was out of step, [my friend] would say, ‘This is not what you have taught me, what you're about,’ and because I respect my friend in that relationship, it would land within my spirit differently … [establishing those trusting relationships] requires us to make investments in communities.” Building community leadership might look like:

- Community violence intervention leaders leading strategy sessions to identify meaningful local solutions that are already in place.

- Firearm suicide preventionists engaging with the owners of gun shops and firearm ranges to highlight their role in prevention.

- Advocates for domestic violence survivors calling for measures to ensure that service providers are able to share information about firearms with survivors while doing safety planning.

Developing and sustaining alternatives to incarceration or engaging with law enforcement.

Discussions about legislation tend to dominate conversations about violence and can sometimes overwhelm discussions of other approaches. That’s a problem because “public safety” laws and policies have historically criminalized the very communities that they are meant to protect. The good news is that, whatever their political alignment, we learned that many communities and organizations impacted by firearm homicides and injuries are exploring alternatives to policing — whether because of the legacy of police violence and injustice against communities of color; because of skepticism about the actual impact of policing on making communities and families safer; because of a belief that law enforcement shouldn’t be involved in removing firearms from people at risk of self-harm; or because of deep-seated resistance to government intervention of any kind. Consequently, much local work to reduce injury and death from firearms elevates and strengthens approaches that do not require law enforcement. As one respondent noted, “If we can shift how we understand safety and how we arrive at safety, then I think that we can shift how we understand police and police violence.”

Whatever solution you seek (whether it’s one of these, or something else that’s grounded in your community’s needs and strengths) remember:

You can’t be strategic and comprehensive at the same time.

In other words, think big, but remember that even the most transformative changes tend to happen one step at a time. While many solutions can make a message appealing to many people, when there are too many different options being weighed at the same time, audiences may become torn about what solutions to prioritize. This produces a “formula for inaction,” making it harder to mobilize people. As Lake Research Partners President and political strategist Celinda Lake has said, “You can have it all, but not all at once.”

Your turn:

Naming problems & solutions

- What's the problem?

- What's the solution?

- Why is this a good approach?

Who has the power to make change? What should they do?

No matter how carefully you’ve considered your problem and solution or how precise you’ve been in crafting your message, it won’t lead to change unless it is tailored to and reaches the right people: the person or people with the ability to make change (also called your audience). Your key audience could be large or small; it depends on what you want to accomplish, who has decision-making power, and whose voices would be helpful in agitating for change.

Zeroing in on specific groups makes your work more efficient because you don’t have to educate everyone about why your approach is worthwhile. Instead, your goal might be to persuade a few key decision-makers. From our message testing work, we learned that Californians want their state and federal elected officials and local officials and community leaders to take action to reduce injuries and deaths from firearms.

With that in mind, ask yourself: “Who is, or should be, responsible for making the change I want to see at the local level?” Think about funders, local policymakers, and decision-making bodies (like Boards of Directors or Chambers of Commerce). Be as specific as you can about identifying and naming the person or people with the ability to make change. Think about questions like:

- Is your main audience a person or a group of people?

- What is your relationship with them?

- What motivates that audience to act?

- What tactics might be most effective to reach your audience?

Also remember that audiences have different starting places for how they understand different issues involving firearms. For example, our message testing showed that:

- Most Californians associate community violence involving firearms with “gang violence.”

- Many Californians are less aware that domestic violence involving firearms is a significant problem.

- Firearm suicide tends to make people think about mental health problems and solutions rather than issues related to firearm access.

These are just a few examples of the specific nuances that affect how audiences understand different types of violence, harm, and trauma involving firearms, and each one could have a significant impact on how your message is understood. You know your issue — and your audience — best: Keep these kinds of unique framing challenges in mind as you consider your audience and build your strategy.

Example: Domestic violence involving firearms

For example, imagine you want to engage local leaders around a policy relating to domestic violence and firearms. You know that your audience may not be as aware of the true prevalence of the problem — and potentially less likely to believe that taking action is critical. As you build your overall strategy, start planning for how you will illustrate the depth and urgency of the problem in a way that’s most meaningful to your audience — for example, by using local data or stories.

Your turn:

Identifying your main audience

- Who is the audience you want to reach?

- What do you want them to do?

Who can be mobilized to influence your main audience?

We often hear, “Violence affects everyone,” which means that almost any group you can think of could be mobilized to apply pressure to your audience. Who has the power to influence your main audience? You can think of this group as potential allies.

To make each potential group’s role more concrete, ask yourself what each could do. What role could different groups play, either in a visible, outward-facing way, or in terms of providing background assistance that could help move the work forward? What role do members of these groups want to play?

Here are a few prompts to get your brainstorm started:

- People who own firearms could …

- People who live with firearm owners could …

- Medical professionals could ….

- Legal professionals could …

- Faith community leaders could …

- School officials could …

- Funders could …

- Youth could …

You will know your ask to potential allies is specific enough if you can answer the five Ws listed below (though you won’t necessarily need to include all five in every message):

- Who should take action?

- What should they do? (e.g. sign a petition, attend a community meeting, deliver testimony at a council meeting, etc.)

- When should they do it? (Is there a specific date and time? A particular season or awareness month or week that would make the action more newsworthy?)

- Where will it happen?

- Why is this the right approach?

Here again, consider the specific frames or beliefs about your issue area that your allies might hold and how those might affect what you say and how you say it. What specific framing issues — like stigma against people involved or misinformation about the prevalence or cause of the problem — might affect them, and how can you plan for them?

Your overall strategy will guide how you communicate about the work you’re doing and why it matters. To make the work more tangible, put the pieces together.

Your turn:

Identifying potential allies

- Who are your allies?

- What should they do?

- By when?

- Why?

Example: Addressing community violence involving firearms

For example, imagine that after meeting with local leaders, community members, researchers, and others, you determine that in your community, prevention programs, treatment centers, and violence intervention sites are unequally distributed — and many of the communities impacted have the fewest sites available with resources to support promising practices that keep people safe. When your group investigates how decisions are made about where to situate these sites, you learn that there’s very little data available about the neighborhoods most impacted. There’s some data available at the county level, and even some data at the city level — but the people closest to the work know that differences by blocks, streets, and neighborhoods won’t be captured by that data.

A community member tells you about a promising practice — community-led data collection to document firearm injuries and fatalities, as well as the absence of healing, prevention, and support sites. During community listening sessions, this emerges as a strategy that people are excited about and believe will make a difference. What’s your overall strategy for helping your community get the data it needs to make life saving decisions?

| What's the problem? | What's the solution? And why is this a good approach? | Who is your main audience, and what could they do? | Who are potential allies, and what could they do? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community resources are not being allocated to firearm violence prevention and intervention programs in the neighborhoods that need the most support. Part of the problem is that local data collection is limited. | Long-term support for local firearm injury and death data collection would ensure that the community has current, local data about where firearms are being used — and where prevention and support initiatives could save the most lives. | City council members could pass a resolution supporting firearm data collection and committing to finding a funding mechanism. | Community members can sign a petition to exert pressure to influence local policymakers. At the petition’s website, they can also learn more about how they can be part of data collection efforts and what solutions might be possible in their neighborhood. |

Your turn:

Putting it all together

- What's the problem?

- What's the solution? And why is this a good approach?

- Who is your main audience, and what could they do?

- Who are potential allies, and what could they do?

In summary

Message is never first — it flows from your overall strategy. Your overall strategy is fluid, but essentially it describes the change we want to see in the world and how we think it will happen. To develop your overall strategy, consider questions like:

What is your message strategy?

Your overall strategy guides everything that you do, and media frames around firearm injuries and deaths can shape your audience’s “starting point” for conversations about safety and community-led approaches. But what about your message? How will you — or your messenger — frame the problem and solution, convey the values that matter, and convince your audience to act?

To develop your message strategy, think about:

- Who needs to hear your message?

- Who should convey your message?

- What should they say?

Who is the audience you want to reach through the media?

Before you build your message, it is important to return to your overall strategy and map out who will hear it and who will deliver it. Remember that different groups will have different starting points for approaching this issue, which means that they may not interpret the same message in the same way. While you can’t know every audience member’s background and experience with violence involving firearms, you can anticipate some differences and keep those variations in mind when crafting your overall strategy.

Think about your audience and potential allies you want to reach. Your main audience for a local effort to reduce death or injury from firearms might mean:

- A funder

- A local policymaker or group of policymakers (like the city council)

- A local leader or group of local leaders (like the Chamber of Commerce)

- The decision-making body for an institution (like a school board or the Board of Directors for a community-based organization)

Potential allies can influence your audience. Allies might include:

- Voters or residents

- Community activists

- Homeowners

- Business people

- “The general public”

Media is not an “audience.” Instead, the news media can be an important way to reach key audiences (particularly opinion leaders) — you decide whether that is the case or not as part of your media strategy.

Whoever your audiences are, they will receive messages about firearms against a backdrop of strong — but divided — attitudes about firearms. To learn more about attitudes toward community-led strategies for preventing death and injury from firearms, we worked with Lake Research Partners, a polling firm with deep experience in and knowledge of messaging around firearms and firearm policies, to develop and test messages about community-led approaches to preventing injury and death from firearms with a representative sample of California residents in 2022. We found:

- Communities across the state had a high level of concern about death and injury from firearms: in fact, more than three-quarters of adults we polled statewide (77%) identified firearm violence and firearm suicide in their communities as a major cause for concern.

- Perhaps because they started with such a high level of concern, we didn’t see big changes in people’s attitudes when presented with messaging about preventing firearm injuries and deaths. In fact, fewer than 1 in 10 adults shifted their views over the course of the survey. In other words, people already have fairly strong, preexisting beliefs about firearms and why they matter, against which all other messages and communication will be received.

- Different communities also have very different “starting places” for what they believe about firearms — and what they think should be done to keep people safe. For example, we observed differences across political lines, with respondents who identified as Republican showing more support than Democrats for protecting the right to own firearms.

- Across the board, people of color were more likely than white respondents to be concerned about the prevalence of injury and death from firearms both before and after hearing prevention messages.

- Firearm ownership plays an important role in how messages about firearms are heard and understood: during message testing, we found that firearm owners were among those most likely to be swayed by messages supporting more strategies to fund prevention efforts. However, many firearm owners reported feeling excluded from or dismissed by the mainstream “violence movement.” As one owner observed, “I don’t like arguments with people who say ‘[firearm owners] don’t care about kids’ … I don’t even want to talk to [that person] anymore.”

Of course, firearm owners are more diverse now than ever because during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a large spike in firearm ownership, and demographics of first-time firearm owners changed to include more women of all ethnic backgrounds, Black adults, Asian and Pacific Islander communities, LGBTQIA+ communities, and others.18,21,22,43,44,45 Although people may own firearms for many reasons (like hunting, collecting, and connecting with family), for many firearm owners, self-protection looms large, particularly among communities of color that experience police surveillance.46,47,48 While many firearm owners don’t trust federal policies,21 people of color who own firearms also question whether public safety systems will truly protect them in light of well-documented systemic racism. For example, one owner who is of Japanese and Chinese descent shared his belief that, in the height of the pandemic, “Asian Americans are realizing that you can't just call 911 and have the police save you.”

Communication tip:

State shared goals

One way to bring firearm owners into a conversation about a shared goal of safety for families and communities is to acknowledge the many reasons people own firearms and how important they are in many communities.

For example, you might use phrases like:

- "We know firearms are important to many people for a lot of different reasons ..." or

- "People in this community own firearms for many different reasons — whatever those reasons are, and whether or not you yourself are an owner, we're all committed to keeping each other safe ..."

Your turn:

Identifying your audience

Use this Google sheet to brainstorm possible audiences and outcomes for your campaign — consult your overall strategy so you stay focused on your key audience and potential allies.

Who delivers the message?

Your message will be received differently depending on who delivers it. You may want to choose and train a variety of spokespeople to deliver the message in diverse contexts. The different combinations of potential speakers are your “messenger mix.” Different messengers may be more or less effective in specific situations.

Whoever they are, for a messenger to be persuasive, the audience has to identify with them. That is, your audience needs to see them as someone they share experiences or values with. For instance, we found that rural Californians are more likely than people living in urban areas to say that “they or someone in their family or close friend group has been a victim of gun violence” (41%) — so if you are focused on communicating with a rural audience, you may find it effective to seek out messengers who can directly speak to the audience’s personal experiences of loss.

If your audience does not identify with the messenger, even the most powerful story will fall flat. Ask yourself: What values or experiences will my audience share with our messenger?

Example: Domestic violence involving firearms

“We have to look at who is serving the community …. [they’re a] trusted factor. We have a conference [where] we go get men from the community that have domestic violence experience, assault experience [who] are then talking to the boys and men in that room to build trust.”

Remember that your messengers, whoever they are, will need support and training. Particularly if they have joined your effort because of the pain of their personal experience, as many violence and firearm suicide prevention advocates have, we must honor and protect that experience and be sure everyone we are working with has the support they need to contribute.

Potential speakers for messages about community violence involving firearms

| Messenger type | Things to consider |

|---|---|

| Survivors of violence and their loved ones | Since each act of community violence has a profound ripple effect on families and communities, many different types of messengers can share their authentic, lived experiences as they relate to firearms — even if they themselves haven’t experienced violence. |

| Representatives of the legal system | Consider diversifying beyond police officers and law enforcement who are already quoted often in the news. Other types of criminal justice speakers may include lawyers, judges, and other legal system representatives. |

| Researchers or medical professionals | Emergency room doctors and others who deal with the aftermath of gunshot victims have direct first-hand experience to share. |

| Local educators, business owners and employees, faith community leaders, and other non-medical professionals | Local leaders can hear from their members and be powerful voices to represent different community sectors |

| Advocates, including youth advocates | Advocates from communities impacted by violence can share their lived experience — and “pull back the lens” to talk about broader patterns and solutions. Young people can be powerful spokespeople whose direct experience with firearms is sometimes surprising and often compelling. |

Potential speakers for messages about domestic violence involving firearms

| Messenger type | Things to consider |

|---|---|

| Policymakers | Policymakers (including local policymakers) who have taken on domestic violence as an issue area can be powerful and passionate speakers about systemic change and why it matters. |

| Survivors of domestic violence and their families and loved ones | Survivors of domestic violence are powerful speakers and can share their authentic, lived experiences — and their wisdom about what needs to happen to keep other people safe. |

| Legal professionals | Attorneys, judges, and other legally-trained professionals are often at the forefront of supporting people who are experiencing domestic violence involving firearms through safety planning and legal advocacy. |

| Advocates | Advocates can provide broader context about the realities of domestic violence and connections between domestic violence and firearms, like data or statistics on the substantial risk of homicide with the presence of firearms. Think about advocates who have direct experience supporting people in safety planning — they are uniquely positioned to share lived experience and “broaden the frame” to talk about the picture. |

Potential speakers for messages about firearm suicide

| Messenger type | Things to consider |

|---|---|

| Survivors of firearm suicide and their loved ones | Since each act of suicide has a profound ripple effect on families and communities, many different types of messengers can share their authentic, lived experiences as they relate to firearms — even if they themselves haven’t experienced a suicide attempt. |

| Mental and behavioral health specialists | Those who have helped people avert tragedy — and those who have seen tragedy firsthand — will have important stories to tell about preventing death and injury from firearms. These speakers may be particularly powerful since many audiences think about firearm suicide as primarily a mental health issue. |

| Law enforcement | Based on suicide prevention research, for broader media and public messages, engaging law enforcement both in an educational capacity and as trusted messengers to certain communities of firearm owners may be powerful.49 By contrast, in other communities, law enforcement representatives may not be viewed as trustworthy, creating barriers to effective communication.33 |

| Firearm owners and their families | Firearm owners are more likely to be skeptical of messengers without firearm experience. Consider messengers who may not have expert titles, or represent law enforcement, like someone who keeps a firearm as part of an emergency “go bag” or an individual whose shooting activities are a form of community bonding. Of course, it may not always be possible for a firearm owner to deliver your message. If your messenger does not own a firearm themselves, acknowledge that difference early on, then pivot to shared goals and values around safety. |

We know that messages from the “gun violence prevention” movement that gain media traction have often been delivered by white people — as one long-standing advocate, Shannon Watts, the founder of Moms Demand Action, herself a white woman noted, “because I was a suburban white mom … I was considered credible by fellow white women, the media, and lawmakers.”

While Ms. Watts may have been a credible messenger for some audiences, others have failed to grasp the extent of the problem and the range of viable solutions because the “messenger mix” was so limited. We know that credible, powerful messages need to come from the people most impacted by the problem and most knowledgeable about solutions — many of whom are people of color, whose work has too often been minimized or made invisible. Again and again, we heard people talk about the need to center “[people who are] most impacted, who're not being represented at the table … not speaking for them but uplifting their experiences and their proposed solutions as strategies.“

Communication tip:

Groups centering BIPOC communities

Several organizations are leading efforts to ensure that people of color are centered and elevated in conversations about firearms, violence, and what to do to keep communities safe, including:

Your turn:

Selecting messengers

Use this Google sheet to brainstorm possible messengers and the values or experiences they might share with your audience.

What do messages include?

We know that strong messages about community efforts to reduce injuries and fatalities from firearms:

- Evoke shared values

- Name a problem — and a solution — that "match"

- Show "the landscape"

- Include a call to action that helps people see what they can do next

- Show what success looks like or can look like

- Acknowledge complexity and discomfort

- Use plain language

Evoke shared values

People’s deeply held values — the principles that guide how they think the world should work — are what they connect with. Values are the “spark” that turns communication into action. A values statement isn’t the whole message or even the lengthiest part of it, but values are important and, whenever possible, should lead your statement: our research found that, across audiences, messages that named core values early swayed respondents the most.

Some of the core values that resonate with Californians when it comes to reducing death and injury from firearms are:

| Values | Things to consider | Example language |

|---|---|---|