Building relationships with editorial boards: A strategy to increase news coverage of health and social justice issues

by: Heather Gehlert

posted on Friday, March 29, 2019

Fetal assault. Child abuse. Manslaughter. Those are just a few of the many charges that a woman in the United States could now face for terminating or even losing her pregnancy through miscarriage. Although a woman and fetus are connected, the rise of so-called fetal personhood — the concept that a fetus should be recognized as a completely separate entity with the status of a fully formed person — has led to a growing number of state and federal regulations that give fetuses extra legal protections while stripping them from women.

These regulations will come as no surprise to the advocates who are working tirelessly to preserve a women’s reproductive freedom and support our health. But they may be surprising to the broader public because such laws typically garner little attention from mainstream news outlets. That’s why a recent eight-part series on this subject from the editorial board of The New York Times caught our attention at BMSG. It covers everything from the connection between the war on drugs and fetal rights to the trauma inflicted on children when their mothers are jailed to the disproportionate impact of feticide laws on poor women and women of color. Such in-depth coverage on any topic would be remarkable, even more so for an issue as fraught as fetal personhood.

We wondered: How did this issue come to the Times’ attention, and what led to their editorial board’s decision to cover it so thoroughly? Turns out there is an important back story, one involving a months-long process and the deep expertise and steadfast work of reproductive health and justice advocates who helped make the series a reality. According to the website of the National Advocates for Pregnant Women (NAPW), a nonprofit that works to protect pregnant and parenting women’s rights, health, and dignity, the coverage captures “the core issues, frameworks, and cases NAPW has worked on for more than 17 years.”

To learn more about the context for the series, the process of working with editorial boards, and how other advocates can use similar strategies to shape news coverage and advance policies that support health, I talked with Lynn M. Paltrow, NAPW’s founder and executive director. Below is a transcript of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

With the 46th anniversary of Roe v. Wade earlier this year, we saw a lot of news coverage about the right to abortion being at risk. And fetal rights, at their core, are about ending legal abortion. Can you explain how the two are linked?

Those who oppose the right to abortion have looked very carefully at that Supreme Court decision and tried to find its weak places where it could be attacked. One of the core findings in Roe v. Wade is that there is no stage of development when fertilized eggs, embryos, or fetuses constitute separate constitutional persons. One of the long-term strategies of the anti-abortion movement has been to use that to create a basis for overturning Roe. Their strategy has been to try and establish in as many different places, in as many different laws, this idea that fetuses are, in fact, now being recognized as separate constitutional persons, or as “persons in the whole sense.” And now, the focus is no longer only on fetuses; the laws that they try to pass would treat fertilized eggs and embryos as completely separate entities. In other words, there would be a recognition of state power on behalf of the, quote unquote, “unborn” from the moment a woman is carrying a fertilized egg.

Still, abortion is not the only right at risk. What are some of the less frequently reported restrictions that women could face when laws treat a fetus or fertilized eggs and embryos as completely distinct from, rather than still inside of, the pregnant woman?

It is clear to us, based on all of the different kinds of cases National Advocates for Pregnant Women has worked on or documented, that there is no way to add fertilized eggs, embryos, and fetuses to the community of constitutional persons without subtracting pregnant women. If there comes a time where fertilized eggs are recognized as separate persons, it will mean that women, the people with the capacity for pregnancy, will be relegated to a separate, unequal second-class status. Virtually every single right we associate with constitutional personhood would be taken away from pregnant women — and even women who are not yet pregnant.

Can you give some examples?

When Angela Carder was critically ill and somebody in the hospital raised the question of whether she could be forced to have cesarean surgery to give her 25-week fetus a chance for life, the judge ordered that surgery over the objections of Angela, her Catholic parents, her husband, and all of her doctors. The surgery was ordered with the understanding that it could kill Angela Carder. They took her out of the intensive care unit. They brought her down to the surgical ward. They cut her open, and they delivered what was a nonviable fetus. The fetus survived for a few hours and died, and Angela Carder died two days later — the cesarean surgery listed as a contributing factor. She was denied the right to life and physical liberty.

So-called fetal personhood measures would really give fetuses more rights than any living person has because no child, no living person, has the right to force somebody else to undergo any medical procedure for their benefit without their consent.

In the name of separate rights for eggs, embryos, and fetuses, pregnant women have been denied medical care and have been forced to give birth while shackled and subjected to grossly disproportionate penalties. They have had bail deliberately set at levels so high that they were forced to remain in jail. These deprivations have taken place after court proceedings where women were represented by inadequate counsel or no counsel at all and where they had no meaningful opportunity to challenge the claims being made against them.

Pregnant women have been secretly searched and had their confidential medical information disclosed. They have been coerced into having unwanted abortions, and they have been penalized for giving birth, for experiencing pregnancy losses, and for terminating or seeking to terminate a pregnancy.

Pregnant women, no less than others, have rights to bodily integrity, due process of law, and to not be subject to cruel and unusual punishment, but basically, by becoming pregnant, women become subject to state control, and things that otherwise would not be criminal, like falling down a flight of stairs, are transformed into crimes because of pregnancy. All of this violates the right to equal protection of law as a matter of sex discrimination and, given the clear targeting of and disproportionate state interventions on Black women, also as a matter of race discrimination.

All of these examples seem incredibly newsworthy, but I haven’t heard much about this in the mainstream media, despite monitoring the news daily. For example, I did not know until I read The New York Times‘ series that at least 38 states and the federal government have laws that recognize fetuses as potential crime victims, separate from the woman carrying the fetus. Why do you think there isn’t more mainstream coverage of these issues?

There is plenty of news coverage, but it is not about the implications of these laws. The laws typically come about — and this is part of the very long-term strategy — after a horrible attack on a pregnant woman. Very often, the pregnant woman is brutally beaten, and in many cases, not only does she die, but the fetus dies, or she survives and she loses her pregnancy. [Anti-abortion advocates] use that as an opportunity to argue that there have been two deaths and then use that to pass the feticide law. So, the media coverage is about violence against women, and these laws are sold as measures that are going to protect pregnant women and their unborn children from violence. [Newsrooms are] not tapped into [other implications of this legislation] because there haven’t been organizations that bring it to their attention.

Although these laws are passed based on claims of protecting women from violence, there is not a single study that has ever been done to show that violence against pregnant women has been reduced in states with feticide laws. And no media outlet has done anything about this as far as we know. These laws can even make women more vulnerable to violence. We’ve actually come across cases where men who have been arrested for beating up pregnant women have said, “Well, I was beating her up because she was doing drugs that might harm the baby, and I was trying to keep her from doing that.”

I understand that the National Advocates for Pregnant Women was involved in the Times’ series. How did the idea come about, and what role did your organization play?

I had an op-ed published in The New York Times at the very end of last summer. It was given the title of “Life After Roe,” and it was articulating the things that we know from our research — in addition to losing the right to abortion — that might happen if [Brett] Kavanaugh was confirmed as a justice of the United States Supreme Court.

A couple of days after that op-ed ran, I received an email from Lauren Kelley, who is on the Times’ editorial board, asking if I would be willing to come speak to them. They were very interested in what I had said in that op-ed. So, Shawn Steiner (NAPW’s media and communications manager) and I went over, and I did not know what to expect, so I just spoke very frankly about how complicated these issues are, and that if their goal was to address criminalization and the question of whether pregnant women are full constitutional persons, then they would have to really take on many issues at once.

Among those would be how a drug war and the crack baby myth were used to help establish the notion that fertilized eggs, embryos, and fetuses should be treated as separate. They would have to address the fact that the greatest threat during pregnancy is not their own mothers, but social determinants that long predate ever becoming pregnant, and how the law is using arrests and the child welfare system to particularly target Black and Brown women more than white women. A couple of days after that conversation, they asked if we would come back. We did, and at that point, they said they wanted to do a sort of editorial series based on many of the things that we had talked about.

We were incredibly lucky to have Shawn Steiner on our staff, but I think she would agree that this series did not come about because we had a magical media person who made it happen. It was my work over the course of my career, the 17 years of National Advocates for Pregnant Women’s work, our research, our cases, our persistence, and the wonderful coincidence that our work now coincided with The New York Times having built an editorial board that was much more diverse than it has ever been, including feminists, including people working on race and class issues, so that there was an awareness of and commitment to the kinds of issues we were working on. And we happened to be there at the right moment.

And once they started that process of research and conducting their reporting, did you act in any kind of advisory role? Did you connect them with sources? Was there a continued relationship there?

Well, as we left that second meeting, they kept thanking us. I was like, “No, no, no, it’s our pleasure.” Little did I know that they were giving us advance thanks for the many requests they had, for everything from pretty much every bit of data we had about arrests and detention for pregnant women to case files to introductions to people who might be willing to do opinion documentaries for the video. And so all of our staff participated in gathering information, analyzing data, figuring out which, if any, of our clients might want to and benefit from being interviewed for an opinion documentary, making the introductions, and answering questions from everyone on the Times’ staff, including the different editorial journalists who were researching each of the topic areas, the graphics, and material for video.

There was a tremendous amount of work, and we made an enormous number of referrals to colleagues, allies, and other experts who they should be speaking with. We were very pleased to see that so many of the people we suggested they talk to, they had, in fact, talked to and included in the series. They are real journalists, so not everything in there is NAPW material or people. They did the hard work of checking everything we said and much, much more. There were whole teams — more than 10 people — working on this, including the photographer. Not to mention the people who had to deal with layout and putting it online.

Let’s talk a bit about stigma. BMSG research has found that news coverage often reflects and reinforces stigma around abortion, at least in part by personifying the fetus. We also know that the language used to describe an issue can make it easier — or harder — to counter opposition arguments. So, that leads me to wonder if you have concerns about the term “fetal personhood” — could it be problematic in news coverage? Is there any other word, phrase, or approach that you would like to see reporters use instead?

It’s always a challenge to come up with succinct language for very complex ideas, but we often use the litany of “personhood for fertilized eggs, embryos, and fetuses” because that is an accurate description of what the anti-abortion advocates are seeking. I have to say that both in news coverage and especially in legislation, it is the case that a bill will be proposed to, for example, prohibit fetal assault or expand the homicide laws to reach the killing of a fertilized egg without ever acknowledging that that law, by definition, has an impact on pregnant women.

While I think the federal government and every state require an economic impact analysis of every piece of legislation, the status of women is, in fact, so low in this country, it doesn’t even occur to legislators to acknowledge or explore what the implications of such laws will be for pregnant women. And the media rarely say, “Well, wait a minute. If fetuses are persons, what does that mean for the personhood of pregnant women?”

We’ve found, through our research at BMSG, that one factor fueling stigma is the absence of women’s voices from coverage. So, it stood out to me that women’s experiences were central to the Times’ series. Was that a strategic decision?

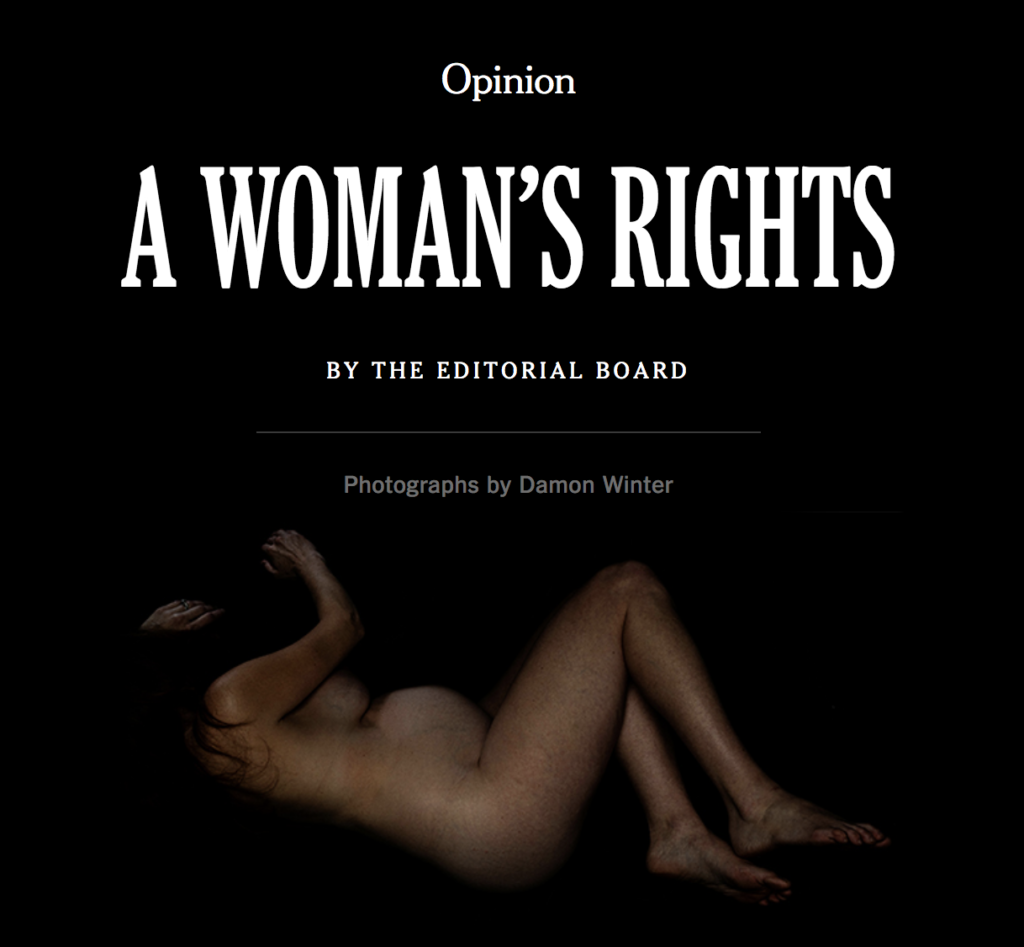

There were a lot of incredibly smart and sensitive people on this editorial board — a whole group of people who have an awareness that the news is about people, and that policy is about people. But I did call back one day to ask about the graphics. I said, “Please, I hope that you will not be using, in any of your graphics, a picture of the disembodied pregnant belly.” Instantly, they said, “Absolutely not. We are focusing on the whole woman.”

When it finally came out and I saw that the title was “Women’s Rights,” not more limited abortion or even reproductive rights, and that the opening photograph was of a whole woman’s body, I knew that what was to come was going to be very good and reflective of the experience of actual people’s lives.

And I do want to say that there were other media outlets, like ProPublica and Rewire, that had been covering some of this. The New York Times recognized these outlets’ work through their social media and promotion of the series.

What do you think we lose when other news coverage does not feature whole women in that way?

It makes it possible to do a vast amount of dehumanization. I think that in this moment where you have #MeToo, people have been somewhat amazed by the number of assaults on pregnant women, the number of ways in which women have been sexually abused and taken advantage of. But I think there is so much sexism hiding in plain view that we don’t see it. This is probably much more true for white women than Black women because Black women experience both the racism and the sexism in a daily way that I think many white women avoid and may not even realize exists until, for example, they go to give birth and somebody is suddenly saying, “You must have cesarean surgery.” That may be the very first experience they’ve ever had with outsiders’ control of their lives.

Besides general visibility and featuring women in a really prominent way, what are you hoping that this series accomplishes, and are you seeing any signs of success yet?

Well, not everybody reads The New York Times. I don’t think we have an illusion that it’s going to dramatically change anything overnight. We are hopeful that it is the beginning of a new conversation, in which people have a much better understanding of the enormous range of harms that will occur if Roe v. Wade is overturned, the enormous number of harms that occur to all pregnant women as a result of anti-abortion measures. When I say all pregnant women, I mean all pregnant women, including those who identify as adamantly pro-life because when women are arrested for fetal endangerment or whatever crime the local prosecutor has made up, they don’t care if the woman is pro-life or pro-choice.

This series may help people understand why it is that we’re still fighting because we have so far, still, to go. I also think it clarifies how intersectional these issues are, that there are many positive alliances to be made between those who want to preserve legal abortion and those who are opposing mass criminalization and mass incarceration, between those who understand that drug issues are health issues that need to be regulated through the public health system, not the criminal law system. And, I think the series shows that we have to work together to end racism because it is often racism that has justified the denial of access to health care and the use of criminalization as the primary response to key human health issues.

So, I think there’s a very optimistic, positive set of alliances and collaborations that might be encouraged over the long haul by this series. In addition, many have never seen the kind of apology made in the series about the contribution The New York Times made to the crack baby myth, including a reporter who, very honestly and bravely, acknowledges how she participated in perpetuating and promoting that myth. I think Janine Jackson (from Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting) raises a very fair question about the series: Is that enough? What will happen at The New York Times and other papers to prevent that from happening again?

We were talking earlier about featuring a whole woman, having her completely inside of the frame, but these stories are not just about any one individual woman. A lot of times, journalists, to humanize a story, will pick out an example of a single individual, but what else should the coverage include? What kind of systems and structures should reporters be highlighting in future coverage?

Any time that there is an attack on abortion, I would hope that the frame would say, “This is not just about abortion. It’s about the people who sometimes need abortions. How is that going to affect their lives?” Also, we know women, in particular, make their decisions in relationships with other people. So, who else should be in that frame? The children they already have, the children who are in the waiting room, the children who they have no place to bring when they have to go for their extra ultrasound or their three trips to the abortion clinic that’s hundreds of miles away. The true story almost always includes the other people in their lives, so they should be in the frame as well.

In your case, multiple media advocacy strategies — writing op-eds and working with editorial boards — were linked. But the latter seems less common. What are some of the benefits to working with editorial boards?

Having worked in many nonprofits over the course of my life, I think there are lots of folks who say, “Hey, you win an issue or you address an issue by writing letters to the editor, and op-eds, and you demonstrate, and here are some of the tools for expanding arguments, opening people’s minds.” One does those things in the hope that they will eventually have an impact, and sometimes the timing is right and they do have that impact. I’m not sure that there is a magic toolbox that gets you to the editorial board of any newspaper or any institution. I think what we should be talking about is, how do we make sure those institutions survive so there are editorial boards that can highlight these issues?

Excellent point. It is a tough time for journalism, and not everybody gets to work with editorial boards. Since you had that opportunity, can you shed some light onto the process? Did anything surprise you?

One of the things I did before I went to the first meetings — I tried to do my homework — was to read about every person on the editorial board, and I tried to figure out where they came from, what their backgrounds were, and who brought with them experience on the intersectional issues that we work on — people who are writing, already, about race, drug policy, and the child welfare system. It was a privilege to get to work with these seasoned, serious journalists and a very pleasant surprise that they understood our extremely intersectional, complex set of issues in a very profound way.

And I have to admit that I found it a little bit validating after having started NAPW and having, year after year, people gently — or not so gently — arguing that I should be able to explain the organization better in one or two sentences. I never disagreed, but I also never did it very well, and now I can say, “Well, this is what it looks like.” It took The New York Times an eight-part series to begin to articulate the kinds of implications that anti-abortion measures have for all pregnant women. And there are many other issues they could’ve gotten into because it is about every aspect of a woman’s life.

What advice do you have for other advocates who want to build relationships with editorial boards?

I’m flattered that I might be considered a person who can give that advice. I will say that learning from other people in the field, occasionally, when I’ve gone to another city, I have reached out to the editorial board at a paper and sometimes been invited to come over and have coffee. I’m not sure I can think of a time where that resulted in much. I think it is about persistence, extraordinary persistence, and developing expertise. We’ve used every educational outreach tool that we can muster. So, for all these years, we’ve done conferences. We’ve done continuing legal education programs. We’ve done small videos. We’ve done webinars. We write letters to editors. We use all of the tools we can in the public education communication toolbox.

What’s next for NAPW’s media outreach? Do you think the Times coverage will open doors to more collaboration — with them or other news outlets?

NAPW will continue our multifaceted outreach to media. In terms of The New York Times specifically, we will keep trying to get our opinions on the op-ed page and in the letters to the editor. Also, while the editorial side of the newspaper in The New York Times is separate from the news reporting side, the big hope is that somehow the series will have an influence on journalism at the paper and in general. So, the next drug scare, the next thing that targets pregnant women as the greatest risk to their children will be covered differently, will rely on science, not panic, and will not allow coverage to be influenced by racism.

NAPW has been working on behalf of pregnant and parenting women for more than 17 years. If you could fast-forward another 17 years, what do you hope the new narrative on reproductive health and justice could be? What’s the headline you’d like to see?

It would start with the United States finally recognizing that health care is a human right, and that that right is for everyone, including the people with the capacity for pregnancy. And all of their health care needs, including abortion and maternity care, would no longer be thought of as special, separate needs or accommodations for a separate, second class of persons.

Anything else you’d like to add?

Don’t give up saying the truth and doing your work. There is an illusion that these things come about because of the media industrial complex or the media consulting industrial complex, and sometimes it’s just because you’re in the right place at the right time, and you continue the effort long enough to be able to take advantage of the moment.