Communicating about the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act of 2021: An analysis of news, social media, and campaign materials

Monday, November 15, 2021Public health practitioners around the world are excited about the potential of sugary drink taxes for protecting the public’s health. Based on the success of the first sugary drink taxes in Berkeley, California,1 the Navajo Nation,2 and Philadelphia,3 and the long history of successful tobacco taxes, we know that sugary drink taxes could help ensure that whole communities avoid premature death from type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and other nutrition-related chronic illnesses.

Sugary drink taxes also generate needed revenue for cities that have been economically devastated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Cities including San Francisco, Philadelphia, and Denver have used sugary drink taxes to fund food and nutrition programs,4,5 renovations to outdoor spaces,6 and other community needs during pandemic-related shutdowns.

The most recent effort to pass a tax on sugary drinks in Washington, D.C., was intended to raise funds to reduce long-standing health inequities in the city. On March 29, 2021, six of Washington, D.C.’s, city council members introduced the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act of 2021. Councilmember Brianne K. Nadeau, who spoke on behalf of the group, cited persistent and pervasive health disparities “made even more apparent by the COVID-19 pandemic”7 as the catalyst for the proposal.

Opponents and proponents of the D.C. proposal debated the legislation in the media. News coverage provides a window into the public narrative about any issue because news shapes the public and policy agendas.8,9,10,11 Journalists’ decisions about how to cover the many pressing topics of the day can raise the profile of an issue; whereas issues not covered by the news media are often neglected and remain largely outside public discourse and policy debate.10,12 News coverage influences how issues are perceived and discussed13,14 including, for example, whose perspectives are seen as credible and valuable, which solutions are elevated or ignored, and how arguments are characterized.

About the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act

The Nutrition Equity Amendment Act proposed to implement an excise tax of $0.015 per ounce on the distribution of sugar-sweetened beverages in Washington D.C, a replacement for the pre-existing 8% sales tax on soft drinks (defined as “a beverage with a natural or artificial sweetener that contains less than 100% juice; or a beverage that is less than 50% milk, soy or other milk substitutes; or coffee, coffee substitutes, cocoa, or tea”a). The initiative was expected to raise $22-30 million in revenue to fund improvements in access to healthy food, expansion of nutrition education programming, and extension of local grocers to communities without access to healthy food. The intended primary beneficiaries of these programs were local families, and individuals housed in shelters and transitional housing in D.C.

During the proposal’s first public hearing in May 2021 many small business owners spoke against the tax. The Alliance for an Affordable DC, a community group bankrolled by the American Beverage Association, enlisted small business owners, many of them people of color, to highlight “the devastating economic consequences a new tax would have on D.C. residents, especially as [the] community begins to recover from the pandemic.”16

Councilmember Nadeau withdrew the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act on June 11, citing insufficient support. In her statement, she accused the beverage industry of “standing in the way of community-based solutions to address health disparities.”16

a Office of the Chief Financial Officer. Tax Rates and Revenues, Sales and Use Taxes, Alcoholic Beverage Taxes and Tobacco Taxes. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://cfo.dc.gov/page/tax-rates-and-revenues-sales-and-use-taxes-alcoholic-beverage-taxes-and-tobacco-taxes.

Across all forms of media, social and health issues are portrayed through a complex process of organizing information to create meaning; this process is known as framing.9,14,15 As they cover stories, journalists select certain arguments, examples, images, messages, and sources to create a picture of the issue. The selection — or omission — of arguments and voices works like a frame around a picture, drawing our attention to what information is important and excluding other information. We are concerned with how the news frames public health and social justice issues because frames foster certain understandings and hinder others.

Because of the great potential sugary beverage taxes have for improving population health and addressing inequities, we also wanted to see how news outlets’ social media platforms (which can also drive news and political agendas) framed the most recent effort to institute a tax. In this report, we present an overview of past research on sugary drink taxes in news coverage and share findings from an analysis of news and social media coverage of the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act.

Sugary drink taxes in the news: An overview of BMSG’s research

Berkeley Media Studies Group has studied news frames of sugary drink taxes since the first explicitly health-focused tax was proposed in Richmond, California, in 2012. In each locale, we have seen that anti-tax spokespeople, often directly funded by the sugary drink industry, have exploited local concerns to argue against the tax. For example, the industry framed a proposed tax as paternalistic and discriminatory toward low-income residents of color in Richmond, a town with a long history of racial divides. In El Monte, California, a city on the brink of bankruptcy, the local American Beverage Association front group highlighted the government’s financial mismanagement and framed its proposed tax as a “money grab.”16 The following year, industry-funded speakers fought a proposed tax in Telluride, Colorado, by evoking the town’s spirit of individualism and arguing that obesity and diet-related diseases weren’t a concern for fit, active local residents.17

In 2014, a proposed tax failed in San Francisco, in part because of the sugary drink industry’s exploitation of residents’ existing concerns about affordability: Indeed, the anti-tax front group was called the Coalition for an Affordable City. The nearby city of Berkeley, California, a town known for its support of progressive initiatives, passed the nation’s first soda tax that same year. The success of the initiative came despite the sugary drink industry’s campaign, which focused on exemptions and loopholes, and argued that the tax didn’t go far enough to improve health.18

In 2018, Seattle, Washington passed a sugary beverage tax that the city’s then-mayor explicitly framed as an effort to raise funds for programming to address racial disparities for local low-income communities and communities of color. The beverage industry’s response built on the attention to equity, with opponents denouncing the tax itself as both racist and regressive.19

Our analysis of the D.C. proposal builds on findings from these prior studies and explores questions like:

- How does the beverage industry’s practice of creating front groups to voice their concerns — known as “astroturf”20 rather than real grassroots — manifest in D.C.? Prior research has shown that the beverage industry’s funding of “community voices” is rarely highlighted in the news.

- What arguments are used in news coverage and on social media? Although the beverage industry tailors its arguments against taxes to local contexts, the core arguments themselves are remarkably consistent and focus on the presumed disastrous economic impact of the tax on local businesses. By contrast, tax supporters typically focus on the health benefits of the tax or bad behavior by the sugary beverage industry.

- Are arguments about racial and health equity present in the coverage? Opponents tend to denounce taxes as regressive and harmful to low-income people, while tax supporters often argue that the sugary drink industry’s targeted marketing to communities of color is itself regressive and racist.

What we did

We evaluated traditional news coverage, tweets, and a sample of emails distributed by the Alliance for an Affordable DC to community partners.

Traditional news

We used LexisNexis and Google News to collect all articles that referenced the proposal (using all variants of the proposal’s name, as well as keywords like “sugary drink tax” or “sugary drink tax” and “Washington D.C.”). We coded the articles we collected using a validated coding instrument that we have used to assess sugary drink tax news from around the country and for which we have previously achieved intercoder reliability (Krippendorff’s alpha > .8 for all variables21).

Tweets

We used the Keyhole social media social listening platform to collect 1,053 posts from Twitter (“tweets”) that appeared between June 1 and June 14, 2021. We used search criteria including hashtags in support of the proposal (#NutritionEquityNow, #4DCHealth, #TogetherforDCHealth) and terms like “sugary drink tax” and “nutrition equity” to identify relevant tweets. Our search terms were designed to exclude tweets related to alcohol and other irrelevant topics.

We then excluded other irrelevant tweets (like tweets about a sugary drink tax proposed in Rhode Island) and any tweets that were geo-tagged outside of the U.S. In addition, because our analysis focused on the content of posts, rather than engagements, when posts were retweeted, we analyzed only those retweets that added content to the original post.

From the remaining relevant 365 tweets, we selected for analysis a random sample of 195 tweets posted in June of 2021. We coded these posts based on the codebook we developed for print news media. Because Twitter exclusively supports abbreviated messages (no more than 280 characters), we simplified the arguments from our print news analysis to include only high-level argument categories: problem definition, product, health, economics, industry, government, and social justice (see Appendix). We also coded tweet authors, and made qualitative notes on any media (images, videos, GIFs, and links) included in the original post. To achieve consensus, we held extensive conversations prior to coding tweets.

Campaign materials

To understand the specific nuances of the messages used by the Alliance for an Affordable DC, we separately analyzed materials produced by the Alliance, including:

Tweets: The Alliance for an Affordable DC posted frequently on Twitter, but its posts did not meet our search criteria because the group didn't use terms like "nutrition equity" or any of the pro-tax hashtags. We manually collected all tweets from the Alliance related to the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act (22 tweets) that were posted during the sample period. We then coded tweets from the Alliance using the modified coding instrument (see Appendix).

Email updates: Representatives from Voices for Healthy Kids provided BMSG researchers with 19 personalized email calls to action sent by the Alliance for an Affordable DC to supporters over the course of the campaign, most of which were sent between March 31 and June 10, 2021. We evaluated the emails using a modified version of the validated coding instrument for print media, including arguments evoked and speakers quoted.

What we found: Traditional news

We found 23 articles about the proposal published between March 29, 2021 and June 30, 2021, mostly in small local outlets or trade publications (see Table 1). Three articles appeared in outlets targeting the Black and Latinx communities (The Washington Informer and El Tiempo Latino, respectively). Most articles about the proposal were news stories (70%). The remaining articles were opinion pieces, primarily op-eds. All but one opinion piece opposed the proposal.

| Table 1: Volume of articles published between March 29, 2021 and June 30, 2021 (n=23 articles) | |

|---|---|

| Outlet | Count of articles |

| Vending Times | 3 |

| WTOP | 3 |

| Washington Informer | 2 |

| The WasteWatcher | 2 |

| The DC Line | 2 |

| EINPresswire | 1 |

| FOX 5 DC | 1 |

| WJLA | 1 |

| NBC Washington (video) | 1 |

| DCist | 1 |

| Blaze Media | 1 |

| WDVM | 1 |

| The Hill | 1 |

| El Tiempo Latino | 1 |

| The Washington Post | 1 |

| California Healthline | 1 |

| Total | 23 |

| Table 2: Volume and type of speakers in news stories published between March 29, 2021 and June 30, 2021 (n=23 articles) | |

|---|---|

| Speaker | Count of articles |

| City or county official | 12 |

| Industry group | 8 |

| Business representative | 7 |

| General “supporters” | 7 |

| Medical or PHA | 6 |

| Academic researcher | 6 |

| Community representative | 5 |

| Policy researcher | 5 |

| News source | 2 |

| Other representative of the beverage industry | 2 |

| Authentic voice | 2 |

| Sugary drink tax coalition affiliate | 1 |

| Opinion author | 1 |

| General “opponents” | 1 |

Speakers

The people most often quoted in the news included city or county officials, the majority of whom spoke in favor of the proposal (see Table 2). Councilmember Brianne Nadeau, who introduced the proposal, appeared most often. Yolanda Hancock, MD, a local pediatrician and supporter of the tax, also regularly appeared in the coverage, often referencing her experiences addressing obesity, diabetes, and sugar sweetened beverage consumption among her Black and Latinx patients: in one widely-reprinted quote, for example, she described the need for a tax to discourage sugary drink consumption, saying, “my youngest diabetic patient is 9 years old. She lost her father to diabetes, her mother has diabetes, her grandmother has diabetes, and after I saw her, she pulled out a Pepsi.”22

Members of the industry-funded Alliance for an Affordable DC also regularly appeared in news coverage. Many of the members of the Alliance identified themselves as local business owners. For example, one anti-tax opinion piece noted, “At least 200 D.C. business owners, who are members of the Alliance for an Affordable DC, signed a letter to the council in opposition. … Joe Park Chau, owner of Menick’s Market, is one of them. … [H]e said ... ‘it’s already expensive to run a business in D.C. … A new tax could determine whether or not our business survives.’”23

Religious leaders also spoke about the tax in the news. Kip Banks, pastor of the East Washington Heights Baptist Church, opposed the tax, observing, “What the [Nutrition Equity Amendment Act] will do is make it harder for poor, struggling families to make it in this city.”22 By contrast, Rev. Bill Lamar, of the Metropolitan Methodist Episcopal Church, decried the beverage industry for “fund[ing] scholarships, [supporting] Black institutions, and … [buying] silence while they sell products that literally destroy lives.”24 Rev. Lamar was one of the only pro-tax speakers quoted in traditional media who was neither a member of the City Council nor a medical professional.

Pro- and anti-tax arguments

Pro-tax arguments focused on positive health outcomes that the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act could produce (52% of articles) and its potential to promote equity and support low-income communities and communities of color (43%). Many speakers evoked the global health crisis posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, including a widely circulated quote from Councilmember Brianne Nadeau, who observed, “One thing that COVID-19 has made abundantly clear is that we need to get serious about addressing health inequities in the District.”25 She also highlighted the fact that low-income neighborhoods in D.C. have “the most limited access to healthy drinks and full-service grocery options,”7 although rates of sugary drink-related disease are highest.

Opposition arguments focused on the economic harms of the tax to local business owners (65% of articles) or community residents (39% of articles). Not surprisingly, many also specifically evoked the pandemic, but they highlighted its economic, rather than health, repercussions. For example, Kirk McCauley, representing several convenience stores, said, simply, “This bill will hurt small businesses when they are struggling to survive.”26 The Alliance for an Affordable DC argued that “the D.C. Council’s bill, if enacted, will directly hurt local shop owners, their employees, and working families who have already been struggling to make ends meet throughout the pandemic.”27 A number of anti-tax speakers specifically criticized the city, stating, for example, “D.C. can find the money in other places.”24

Racial and health equity arguments in the news

Although almost all articles mentioned the full name of the policy, only two included a description or example of nutrition equity itself — one in support of the tax and one against. A rare long-form news article in a Spanish-language paper focused on the health harms of sugary drinks for Latinx D.C. residents and explained that the tax would help address long-standing health inequities affecting this community.28 By contrast, an op-ed opposing the tax dismissed the use of the term “equity” as merely the “term du jour.”23

Opposition speakers regularly decried the tax as inequitable (48% of articles). As one community resident observed: “[A] lot of Black people rely on sugary drinks — it’s cheaper so they buy sugary drinks so that’s going to be unfortunate for people of color. … I don’t think it’s fair at all.”24

What we found: Twitter

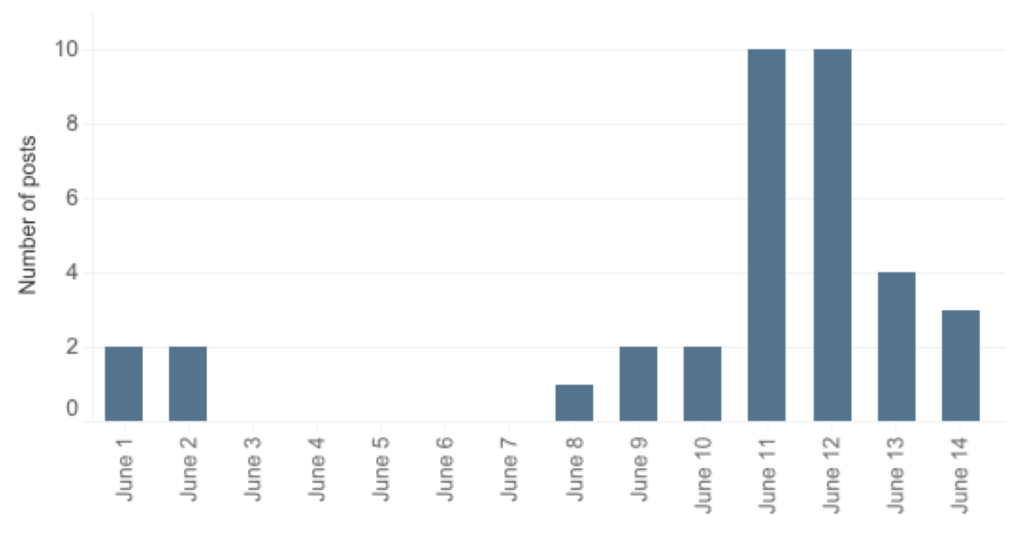

Though we excluded tweets about sugary beverage tax efforts in other states and tweets geotagged outside the United States, our final sample still included many irrelevant tweets (about, for example, beverage industry issues related to labor). In total, just over 18% (36 posts) of randomly sampled tweets were relevant to the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act. Most of the relevant tweets were posted on June 11 and 12 (see Figure 1) and were reactions to the proposal being withdrawn from the D.C. Council’s agenda.

Figure 1: Timeline of sampled tweets relevant to Nutrition Equity Amendment Act* (n=36)

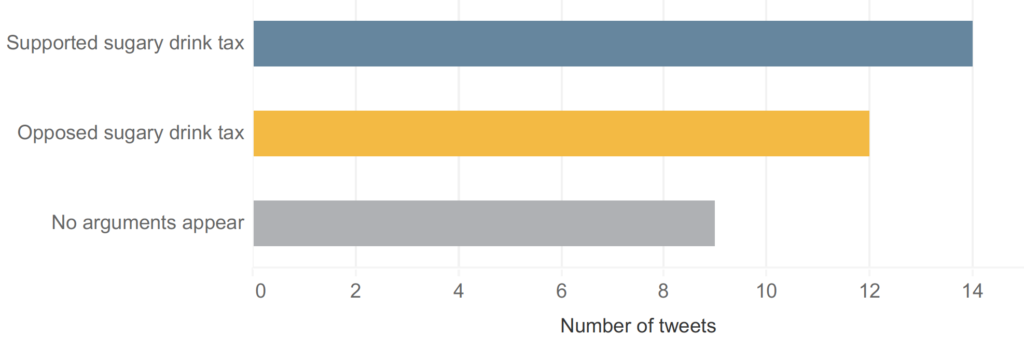

Many tweets included at least one argument either in favor of or opposed to the sugary drink tax. Most tweets include arguments supportive of the proposal (Figure 2), likely because our search included terms favorable to the proposal, like “nutrition equity.”

Figure 2: Arguments in sampled tweets* about the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act published June 2021 (n=36)

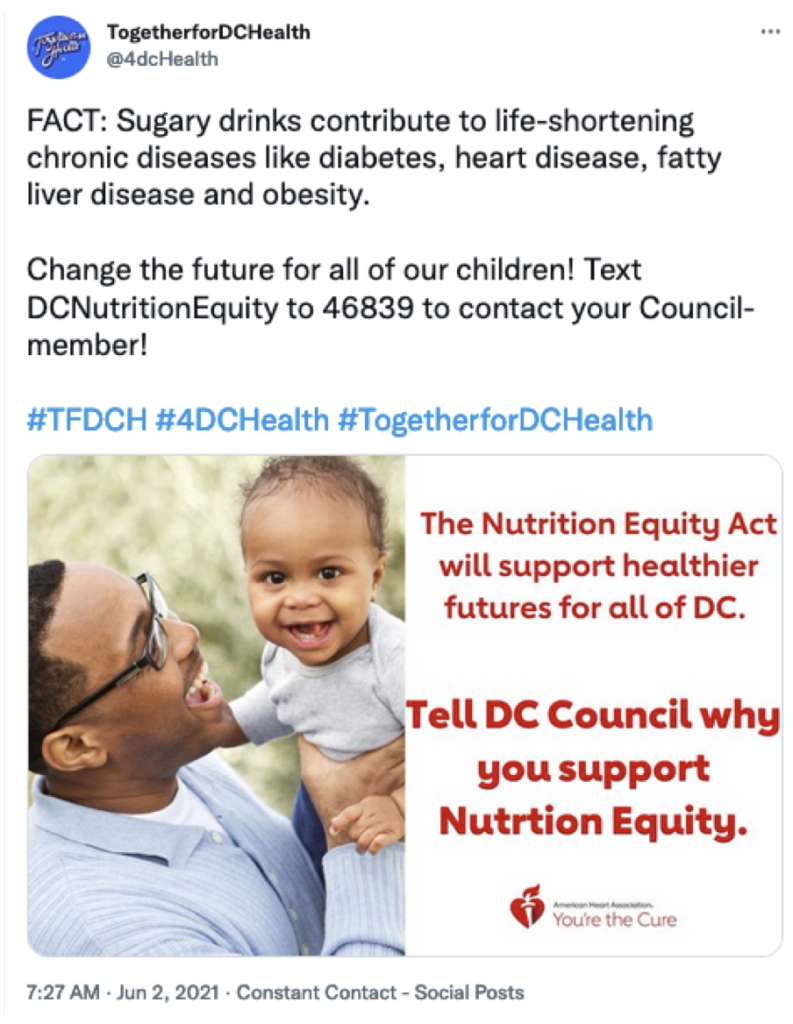

Representatives from the medical and public health fields (21% of tweets), the Together for DC Health coalition (13%), and city government (2%) tweeted in support of a sugary drink tax. Tweets from these authors most frequently addressed health and racial disparities and evoked values of community and protecting children (see Figure 3).

Although medical professionals and public health researchers occasionally used the term “nutrition equity” in tweets supporting the proposal, the term appeared in fewer than one-third of all tweets.

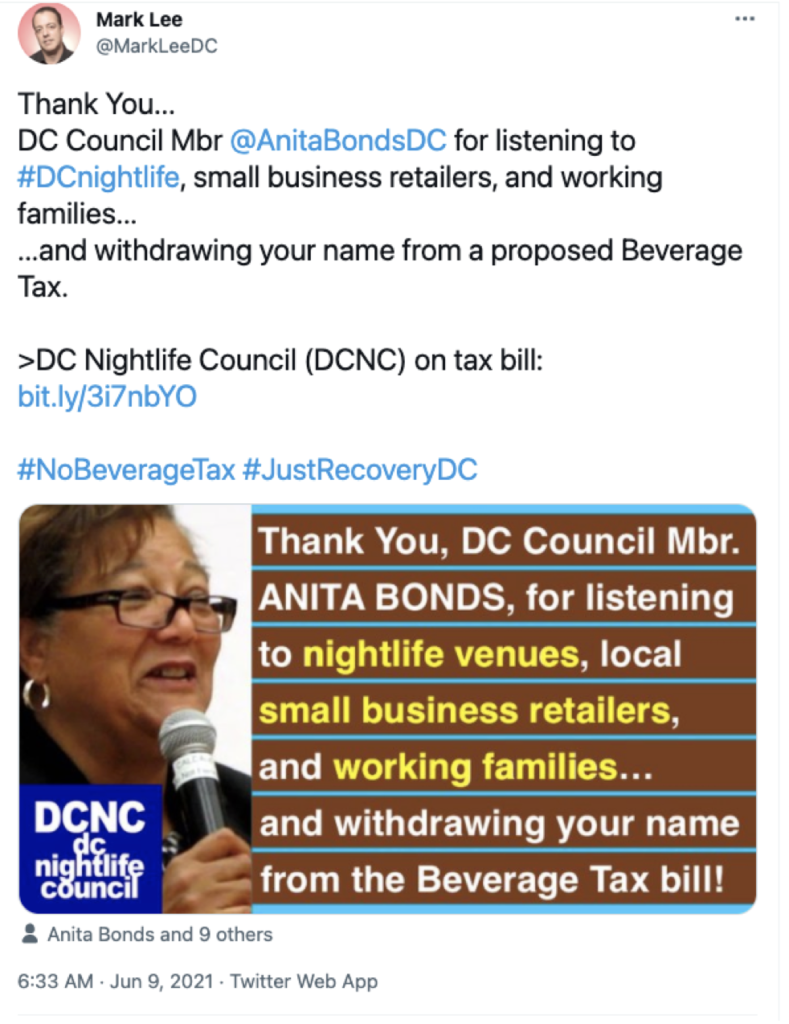

Tweets opposing the proposal argued that it would harm small and minority-owned businesses as they struggled to recover from the pandemic, or expressed concerns about the impact of increased prices on community members. Many who posted tweets opposing the proposal described it as a “beverage tax” and failed to mention sugary drinks at all (see Figure 4).

| Figure 3: Sample tweet supporting Nutrition Equity Amendment Act | Figure 4: Sample tweet opposing the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act |

|---|---|

|  |

| Source: https://twitter.com/4dcHealth/status/1400096694663102466 | Source: https://twitter.com/MarkLeeDC/status/1402619908589039616 |

What we found: Campaign materials from the Alliance for an Affordable DC Tweets

Tweets from the Alliance, like other tweets opposing the proposal, focused on economic arguments. For example, a typical tweet highlighted the remarks of a small business owner, who observed: "It really is prohibitive to small companies like myself.”29 Many tweets from the Alliance (40%) used images to convey economic arguments — often, they featured a business owner of color, arguing that the proposal would harm their business (see Figure 5).

Tweets from the Alliance were unique in that they explicitly framed economic arguments in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic or economic recovery efforts (80% of tweets). Many of these tweets evoked a sense of urgency related to pandemic recovery and urged audiences to act against the proposal (see Figure 6).

The Alliance also used Twitter to cast aspersions on the reliability of Council members themselves or framed them as working against the people of D.C., especially its Black community. For example, one speaker whose recorded testimony was included in a tweet from the Alliance warned, “For the city to throw punches to the Alliance … don’t throw punches unless your house is clean.”30 The same video quoted a community resident who described the proposal as a “tax on Black people” and compared it to voter suppression and racial discrimination.

Nearly all tweets from the Alliance (90%, N=22) used the term “beverage tax” or the hashtag #NoBeverageTax, but only one tweet explicitly mentioned sugary drinks. All other posts from the Alliance avoided mentioning sugary drinks, sugar-sweetened beverages, soda, or any variation of the term.

| Figure 5: Sample tweet from the Alliance for an Affordable DC | Figure 6: Sample tweet from the Alliance for an Affordable DC |

|---|---|

|  |

| Source: https://twitter.com/AllianceforDC/status/1402271701602349063 | Source: https://twitter.com/AllianceforDC/status/1400920300473233408 |

Campaign emails

BMSG researchers analyzed 19 emails that the Alliance for Affordable DC sent to its members, the majority of which were relatively brief (3-5 short paragraphs) and included a call to action. The Alliance repeated three themes in the emails, which parallel the themes that surfaced in the tweets they shared:

- “Your voice matters”: Each email included a call to action to engage recipients in the process of opposing the tax proposal. The specific action varied depending on when in the policy process the email was sent: For example, shortly after the proposal was introduced, emails urged recipients to “contact your councilmember” to “tell [them] to reject this harmful tax.”31 A month later, shortly before a city council meeting, the Alliance encouraged members to submit written testimony opposing the tax and provided a form to facilitate the process.32 The emails highlighted recipients' integral role in the process, reminding them “your voice can make a difference!”33 and “If we are going to stop the beverage tax, the D.C. council needs to hear from you.”34

- “Small businesses are the engines that power our communities”: The emails described small businesses as “the economic engines of our communities” that “rely on the patronage of neighborhood working families.”35 To highlight these small businesses, and the people who run them, most emails included a video or a photograph profiling a local business owner speaking out against the tax. A typical quote came from Muhammed Nooman, who stated, “Our customers depend on us for good and affordable food options, and it will be a lot harder to offer that if the sugary drink tax goes into play.”36 Many of the Alliance members profiled in the emails appeared to be men and women from communities of color.

- The people of D.C. vs. the City Council: Many emails positioned the Alliance and its members as champions of small business owners. Typical subject lines included: “Your local restaurant can’t fight this alone”37 and “We’re defending D.C.’s small businesses — can we count on you?”33 Battle metaphors appeared in the text of the emails, many of which explicitly or implicitly cast the D.C. City Council (sometimes referred to as just “the City”) as an enemy and pitted them against small businesses. A typical email observed, “As working families struggle to make ends meet and small businesses and restaurants fight to recover from the downturn caused by COVID-19, the D.C. Council is proposing a devastating tax.”38 Another cast doubt on the city’s motivations, noting, “The pandemic took a toll on everyone yet, despite a budget surplus of $526 million, some on the D.C. Council are trying to take money out of the pockets of an already struggling city.”39

Summary

Arguments for and against the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act across media

Proposal will cause economic harm to struggling local businesses“Beverage tax” will economically harm local businesses“Beverage tax” will economically harm local businesses struggling to recover from the pandemic

| News media | Industry-funded materials | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Arguments supporting the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act | Proposal will make individuals and the community healthier | Proposal will make individuals and the community healthier | None |

| Proposal will address inequities and benefit low-income communities and communities of color | |||

| Arguments against the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act | Proposal will cause economic harm to struggling local businesses | “Beverage tax” will economically harm local businesses | “Beverage tax” will economically harm local businesses struggling to recover from the pandemic |

| Proposal will economically harm the community through higher grocery bills, etc. | By proposing “beverage tax,” city council is acting inappropriately harming struggling D.C. community | ||

| The proposal is inequitable and harmful to Black communities. | |||

| Speakers | Supporting: City government (Brianne Nadeau), medical representatives (Yolanda Hancock) | Supporting: Public health and medical community, representatives of the Together for DC Health coalition | Supporting: None |

| Opposing: Small business owners affiliated with industry-funded Alliance for an Affordable DC | Opposing: Local small business owners and community members | Opposing: Alliance for an Affordable DC and affiliated small business owners |

Conclusion

Our analysis of multiple types of media about the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act proposed in Washington D.C. revealed that traditional news coverage was sparse. As in previous analyses, supporters of the proposal used arguments that focused on health, while opponents prophesied economic disaster for local small businesses. Speakers on both sides leveraged arguments about racial equity and framed their remarks within the broader context of the global COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on D.C. residents.

We found relatively few Twitter posts that used hashtags or language supportive of the campaign. The few we found tended to echo arguments about health seen in traditional news and, mostly, were posted by public health or medical speakers. Tweets opposing the proposal evoked familiar arguments about the economy.

The industry-supported opposition had a consistent presence on Twitter. Tweets from the Alliance for an Affordable DC regularly included strong arguments against the proposal (which they described as a “beverage tax” without mentioning the focus on sugary drinks) that cast aspersions on the motivations of the D.C. City Council. Emails from the Alliance urging supporters to act used similar arguments and framing but more overtly positioned the Alliance as a champion of small businesses and framed the City Council as an enemy intent on “[taking] money out of the pockets” of D.C. residents.

Though much of the framing of the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act paralleled patterns we have seen in previous analyses of sugary drink taxes in the news, some aspects of the D.C. debate were unique. For example, the news explicitly acknowledged some business owners’ participation in industry groups, in contrast to previous analyses, where the industry affiliation of local business owners was typically not identified.

Racial equity was an important concern in D.C., perhaps because Black people comprise the city’s largest racial group (44%).40 Accordingly, the industry-funded opposition used photos and stories that elevated the experience and perspectives of Black business owners and community leaders (including members of the Greater Washington Black Chamber of Commerce) to an extent we have not seen in news coverage from other cities where the Black community accounts for less of the population.

Finally, and unsurprisingly, the D.C. proposal debate was unique in that arguments evoked the local consequences of COVID-19, an issue that was not relevant in prior analyses. Specifically, proposal opponents explicitly named economic anxiety and harm caused by the pandemic and framed the city council’s actions as especially harmful because of that context. By contrast, those quoted speaking in favor of the tax talked more about health inequities that had surfaced during the pandemic, and the impact of obesity and related diseases on COVID-19 mortality.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this analysis, and our previous evaluations of news about sugary beverage tax proposals, we offer recommendations to inform subsequent communication (with the caveat that all recommendations should be considered in the context of each individual campaign’s overall strategy). Advocates focused on building support for sugary drink taxes can:

Establish shared language and concrete examples of equity that speakers can draw on.

Experts41 have emphasized the importance of centering equity in sugary drink tax policies. However, the term “equity” itself is not necessarily widely understood, and without explanation could be dismissed. In Washington, D.C., the text of the proposal itself illustrated existing inequities and named how the proposal would address them: “[T]he lowest income neighborhoods [have] the most limited access to healthy drinks and full-service grocery options. … The legislation will allocate revenue to programs that increase access to healthy food options, expand community based nutritional programming, and target chronic disease prevention and management.” However, these remarks were rarely quoted in news coverage, and most tax proponents who named the bill failed to describe or demonstrate nutrition equity. Detractors then dismissed it as a “term du jour,” or expressed confusion about its meaning.

Spokespeople will need clear, tangible examples that they can repeat frequently to show what nutrition equity means. A good first step is developing or finding a shared definition of equity that everyone in the campaign can draw upon and illustrate with concrete examples of how the proposal will support nutrition equity. Advocates can also use resources from The Praxis Project42 and Healthy Food America41 to illustrate what is needed to build and maintain equitable, just food systems and communities for everyone.

In Washington, D.C., during the month prior to the June withdrawal of the proposal, proponents tweeted that the funding would “deliver nutrition education, cooking lessons, and healthy shopping lessons at Family Success Centers”43 and used plain language to remind followers that “Longer, healthier lives [are] not just for some #DC residents but for ALL.” Repeating examples like these throughout the campaign and across different media will help them gain traction.

Ensure a variety of community voices (including parents, store owners, etc.) are prepared to speak on behalf of the tax.

Few community members spoke in support of the tax in D.C. news coverage or social media. By contrast, proposal opponents leveraged Twitter and the Alliance’s email listserv to feature local business owners and community organizations, who argued against the proposal.

Community spokespeople, including residents, business owners, educators, religious leaders, and others, are important because they use their authentic voices to remind audiences who a tax will really benefit — residents and other people “just like you and me.” A well-rounded messenger mix that goes beyond government leaders and medical professionals to include parents and young people, local business owners, and other community members will be able to speak powerfully about not only the health benefits of the proposal but also what the funds raised could do to advance equity within the community.

Community voices need training and a range of platforms to speak from, including traditional print news, social media, and online forums that allow democratic participation in public comment periods. Preparing a press kit that includes cohesive and clear talking points, images, and text easily shareable on social media, and instruction for submitting public comment, can give busy community members an effective starting point for becoming louder voices in a campaign.

Be prepared to counter industry messaging and look for ways to make the community — and reporters — aware that the anti-tax coalition is a front group for Big Beverage.

Research from Berkeley Media Studies Group shows that when it comes to obesity, food companies claim to be “part of the solution” while their industry associations do the dirty work of intense lobbying to keep regulation and taxes at bay.44 But, the industry playbook is increasingly sophisticated — simply pointing out these kinds of “astroturf” campaigns isn’t enough. Advocates can also remind people that multinational corporations are trampling on the health of our communities for profit, as Rev. Lamar did in Washington, D.C. when he denounced the beverage industry for donating to Black institutions to silence critics and distract from the harms their products cause.

Social media is one way to counter industry messaging and name bad behavior: Sugary drink tax proponents can use social media to name the companies that are footing the bill to put up a smokescreen to protect their profits while harming community health. In fact, previous BMSG research has found that Facebook and Twitter users were far more likely to like, share, favorite, retweet, and/or comment on posts that discussed the sugary drink industry’s problematic behavior.45

One danger when industry-affiliated spokespeople dominate the news is that the full range of health consequences of sugary drink consumption are left out of the story.46 Another strategy to counter industry messages is to diversify the pool of pro-tax speakers by building relationships with community businesspeople and economic experts (see above). Those speakers can help advocates develop and deliver messages that address not only the health benefits of the tax but also the economic issues that tax opponents are sure to name. For example, local business owners could talk about important community resources that the tax will fund (a theme of the successful sugary drink tax campaign in Philadelphia47) or the long-term economic benefit to the community of investing now in better health.

We can expect that in future sugary beverage tax campaigns, the beverage industry will continue to use race as a tool to divide communities to further its agenda and sell more products. Advocates should call out that tactic when they see it: research from the Race-Class Narrative Project has demonstrated increased support for good policy when advocates point out that greedy actors — like the beverage industry — are using race to divide us.48 Advocates can bring this perspective into their messages, pivot phrases, and other communication materials to illustrate how the industry uses race as a tool to divide and further harm communities.

Be flexible and responsive to changes in industry tactics and the larger political and cultural landscape.

The road to change is rarely straightforward, especially in a rapidly changing political environment and in the face of evolving beverage industry tactics. Advocates must be nimble and prepared to change direction as the situation demands; being patient and willing to adapt pays off. For example, in Washington, D.C., the beverage industry leveraged concerns about racial inequity as a talking point. Being prepared to not only rebut but pivot from these arguments as they emerge is a critical step. Advocates can equip spokespeople with pivot phrases (like “That’s a good point, but I think your audience/readers would be interested in knowing …” or “What’s important to remember is…”) and tangible examples of what nutrition equity means (see above) to help them keep conversations about the tax proposal on track.

Advocates can use social media to clarify why sugary beverage taxes and nutrition equity efforts are more important now than ever — and to correct disinformation spread by the beverage industry and tax opponents. For example, making corrections when the opposition uses the term “beverage tax” can highlight, in real time, that the industry intentionally sows public confusion and uncertainty by failing to mention other components of the proposal or by leaving sugar-sweetened beverages out of the conversation.

Finally, for the foreseeable future, the national and international context of the pandemic will be the scene against which all remarks about any issue, including beverage taxes, are heard and understood. Advocates must be prepared to frame their statements and share examples in the context of the pandemic, as when Dr. Yolanda Hancock made the case for the D.C. proposal by evoking COVID-19 concerns, saying, “[N]early 80% of people who have been hospitalized or died from COVID-19 have been overweight or obese. And the majority of those in D.C. are Black or Brown. Bold steps must be taken.”26

Although the Nutrition Equity Amendment Act was unsuccessful this time, it is another example of communities’ increasing attention to and interest in sugary drink taxes. Few tax initiatives win the first time out. Persistence is key, as is learning from the last campaign to apply its lessons to the next. Developing strong messages and robust communication tactics can help shift public opinion and build support for subsequent proposals that will ultimately support and sustain true nutrition and health equity across the country.

Appendix

Modified instrument used to code social media

| Frame | Arguments in favor | Arguments against |

|---|---|---|

| Diet-related diseases are/are not a high priority problem. | Diet-related chronic diseases are a problem or cost the community/society money. | Diet-related chronic diseases are not a (high-priority) problem. |

| Sugary drinks are/are not uniquely harmful. | Sugary drink/sugar causes negative health outcomes. | Sugary drink/sugar does not cause negative health outcomes. |

| Sugary drink taxes do/do not make people healthier. | The tax will make people healthier because people will consume less sugar, or the tax will fund health and nutrition programs. | The tax will not improve health because people will just buy sugary drinks elsewhere, or the tax won’t raise enough to support health programs |

| Sugary drink taxes are not/are harmful to the economy. | The tax will not negatively affect the economy or will balance the budget. | The tax will economically harm business owners and community residents. |

| Beverage industry does/does not behave badly. | The sugary drink/beverage industry is behaving badly in this campaign, or in its marketing practices. | The sugary drink/beverage industry is behaving appropriately or in the community’s best interest. |

| Sugary drink taxes are/are not an appropriate policy action. | This tax is an example of the proper role of government, or local government is acting in people’s best interest. | This tax is an example of government overreach, and individuals should be able to make choices for themselves. |

| Sugary drink taxes are not/are regressive or racist. | People of color and people with low incomes will benefit from this tax because the sugary drink industry has targeted and disproportionately harmed them. | People of color and people with low incomes will suffer most from this tax; the tax is regressive or racist. |

Acknowledgments

We thank Voices for Healthy Kids for supporting this work. Thanks to Suzette Harris and Terra Hall for their insights and enthusiasm.

We are grateful to Emily Waters of Keyhole for her support in collecting social media data and to Heather Gehlert for copy editing.

References

1. Falbe J, Thompson HR, Becker CM, Rojas N, McCulloch CE, Madsen KA. Impact of the Berkeley Excise Tax on Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(10):1865-1871. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303362

2. Yazzie D, Tallis K, Caleigh C, et al. The Navajo Nation Healthy Diné Nation Act: A Two Percent Tax on Foods of Minimal-to-No Nutritious Value, 2015–2019. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17(E100). doi:https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd17.200038.

3. Bleich S, Lawman H. The Association Of A Sweetened Beverage Tax With Changes In Beverage Prices And Purchases At Independent Stores. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(7).

4. Phillips J. SF soda tax funds find new purpose: fighting hunger during COVID-19 pandemic. San Francisco Chronicle. Published June 12, 2020. Accessed September 29, 2020. https://www.sfchronicle.com/food/article/SF-soda-tax-funds-find-new-purpose-fighting-15334696.php

5. Streetman A. How Boulder’s soda tax is helping fight hunger during COVID-19 – CBS Denver. Published September 10, 2020. Accessed September 29, 2020. https://denver.cbslocal.com/2020/09/10/boulder-soda-tax-funds-healthy-food-coronavirus/

6. Kurtz P. City debuts refurbished playgrounds following virus delays. KYW Newsradio. Published July 21, 2020. Accessed September 29, 2020. https://www.radio.com/kywnewsradio/articles/news/city-debuts-refurbished-playgrounds-following-virus-delays

7. Press Release: Councilmember Brianne K. Nadeau introduces nutrition equity bill. The DC Line. Published March 29, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://thedcline.org/2021/03/29/press-release-councilmember-brianne-k-nadeau-introduces-nutrition-equity-bill

8. Dearing JW, Rogers EM. Agenda-Setting. Sage; 1996.

9. Gamson W. Talking Politics. Cambridge University Press; 1992.

10. McCombs M, Reynolds A. How the news shapes our civic agenda. In: Bryant J, Oliver MB, eds. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. Taylor & Francis; 2009:1-17.

11. McCombs M, Shaw D. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin Q. 1972;36(2):176-187.

12. Scheufele D, Tewksbury D. Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. J Commun. 2007;57(1):9-20.

13. Scheufele DA. Framing as a theory of media effects. J Commun. 1999;49(1):103-122.

14. Entman RM. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J Commun. 1993;43(4):51-58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

15. Iyengar S. Is Anyone to Blame? How Television Frames Political Issues. The University of Chicago Press; 1991.

16. Mejia P, Nixon L, Cheyne A, Dorfman L, Quintero F. Issue 21: Two communities, Two debates: News coverage of soda tax proposals in Richmond and El Monte. Berkeley Media Studies Group; 2014. Accessed August 28, 2014. http://www.bmsg.org/sites/default/files/bmsg_issue21_sodataxnews.pdf

17. Nixon L, Mejia P, Cheyne A, Dorfman L. Big Soda’s long shadow: News coverage of local proposals to tax sugar-sweetened beverages in Richmond, El Monte and Telluride. Crit Public Health. 2015;25(3):333-347.

18. Somji A, Bateman C, Nixon L, Arbatman L, Aziz A, Dorfman L. Soda tax debates in Berkeley and San Francisco: An analysis of social media, campaign materials and news coverage. Berkeley Media Studies Group; 2016.

19. Mejia P, Perez-Sanz S, Dorfman L. Seattle’s sugar-sweetened drink tax: An analysis of local news. Berkeley Media Studies Group; 2020.

20. Appollonio D, Bero L. The creation of industry front groups: the tobacco industry and “get government off our back.” Am J Public Health. 2007;97:419-427.

21. Krippendorff K. The Content Analysis Reader. SAGE Publications, Inc; 2009.

22. Harris HR. D.C.’s Proposed sugar tax sparks racially charged debate. The Washington Informer. Published May 18, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.washingtoninformer.com/d-c-s-proposed-sugar-tax-sparks-racially-charged-debate/

23. barras jr. More than enough money in D.C. The DC Line. Published May 28, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://thedcline.org/2021/05/28/jonetta-rose-barras-more-than-enough-money-in-dc/

24. Fox S. Should DC tax you for buying sugary drinks? The proposal is stirring up a debate. Fox5. Published June 1, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.fox5dc.com/news/should-dc-tax-you-for-buying-sugary-drinks-the-proposal-is-stirring-up-a-debate

25. Juarez L. Council considering Nutrition Equity Bill, tax change on sugary drinks. WDVM DC. Published March 30, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.localdvm.com/news/washington-dc/council-considering-nutrition-equity-bill-tax-change-on-sugary-drinks/

26. Lukert L. Supporters, opponents weigh in on new DC soda tax. WTOP News. Published May 20, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://wtop.com/dc/2021/05/supporters-opponents-weigh-in-on-new-dc-soda-tax/

27. Grablick C. D.C. Lawmakers revive push for controversial tax on sodas and sugary drinks. DCist. Published March 30, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://dcist.com/story/21/03/30/dc-council-pushes-for-excise-tax-on-sugary-drinks/

28. Rodriguez C. El COVID-19 aumentó riesgo de enfermedades crónicas en la comunidad latina del DMV tras consumo de azúcar saturada. El Tiempo Latino. Published June 4, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://eltiempolatino.com/news/2021/jun/04/el-covid-19-aumento-riesgo-de-enfermedades-cronicas-en-la-comunidad-latina-del-dmv-tras-consumo-de-azucar-saturada/

29. Alliance for an Affordable DC. Twitter. Published June 11, 2021. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://twitter.com/AllianceforDC/status/1403366424056320004

30. Alliance for an Affordable DC. Twitter. Published June 3, 2021. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://twitter.com/AllianceforDC/status/1400554129928294401

31. Alliance for an Affordable DC. What You Need to Know About the Proposed Beverage Tax. Published online April 9, 2021.

32. Alliance for an Affordable DC. LAST DAY TO Sign Up! Can We Count On You? Published online May 14, 2021.

33. Alliance for an Affordable DC. We’re Defending DC’s Small Businesses…Can We Count On You? Published online May 13, 2021.

34. Alliance for an Affordable DC. Time is running out! Your voice is your vote. Published online May 7, 2021.

35. Alliance for an Affordable DC. ICYMI: Greater Washington Black Chamber of Commerce Opposes a Beverage Tax. Published online June 10, 2021.

36. Alliance for an Affordable DC. Time is Running Out! Say ‘NO’ to Another Tax on DC Residents. Published online May 26, 2021.

37. Alliance for an Affordable DC. Your Local Restaurant Can’t Fight This Alone. Published online May 9, 2020.

38. Alliance for an Affordable DC. The Time is Now. Working Families Need Your Help. Published online May 4, 2021.

39. Alliance for an Affordable DC. ICYMI: Here’s What Happened at the Beverage Tax Hearing. Published online May 20, 2021.

40. Gathright J. D.C.’s Black residents make up less than half the population, 80% of COVID-19 deaths. NPR. Published May 11, 2020. Accessed August24, 2021. https://www.npr.org/local/305/2020/05/11/853892794/d-c-s-black-residents-make-up-less-than-half-the-population-80-of-c-o-v-i-d-19-deaths

41. Tax Equity Workgroup, Healthy Food America, The Praxis Project. Sugary drink tax equity policy design report. 2020. Accessed August 24, 2021. https://www.thepraxisproject.org/resource/2021/sugary-drink-tax-equity-policy-design-report

42. Duke Sanford World Food Policy Center, Moralez X. How soda taxes can drive equity and community wellbeing. Accessed August 25, 2021. https://www.thepraxisproject.org/podcast-ep/2019/dukesanford-ssb-equity-community-wellbeing

43. American Heart Association Greater Washington Region. Twitter. Published May 17, 2021. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://twitter.com/HeartOfGWR/status/1394389786434187264

44. Nixon L, Mejia P, Cheyne A, Wilking C, Dorfman L, Daynard R. “We’re Part of the Solution:” Evolution of the Food and Beverage Industry’s Framing of Obesity Concerns Between 2000 and 2012. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2228-2236.

45. Somji A, Bateman C, Nixon L, Aziz A, Arbatman L, Dorfman L. Soda tax debates: A case study of Berkeley vs. Big Soda’s social media campaign. Berkeley Media Studies Group; 2016.

46. Somji A, Nixon L, Arbatman L, et al. Advocating for soda taxes: how oral health professionals fit in. CDA J. 2016;44(10).

47. Gehlert H. What Philadelphia’s soda tax can teach us about health framing. Berkeley Media Studies Group. Published June 22, 2016. Accessed August 24, 2021. http://www.bmsg.org/blog/what-philadelphias-soda-tax-can-teach-us-about-health-framing/

48. Anat Shenker-Osorio, Ian Haney-López, Heather McGhee. The Race-Class Narrative Project. Accessed May 15, 2019. https://www.demos.org/race-class-narrative-project