Finding that safe space: News about domestic violence and homelessness in California — and finding opportunities to build narrative power

Thursday, May 30, 2024Introduction

We all want to see our fellow Californians safe and stably housed. Everyone deserves a space to call home, and advocates have worked toward this goal for decades. Similarly, journalists have written an abundance of articles about the state’s housing crisis and efforts to end it. Yet a driving factor behind the crisis is going largely unreported in news coverage: domestic violence.

News coverage rarely elevates the reality that as many as 57% of all homeless women report domestic violence (DV) as the immediate cause of their homelessness,1 or that 80% of unhoused women with children say they have experienced domestic violence, according to multiple studies.2,3 News outlets also frequently overlook how factors like the high cost of housing, under-resourced and overcrowded shelters that fail to take into account the needs of survivors, and discrimination from landlords against DV survivors all make it difficult for women to leave abusive situations.4 Other systemic barriers complicating the issue but often left out of stories about housing include low wages, increased caregiving duties, and mortgage lender discrimination against women.

Some studies have also found gaps in the coverage of Black, Latine, and Indigenous groups who experience disproportionately higher rates of homelessness and DV,4 while over-representing their white counterparts in the news.5 Housing discrimination is also prevalent among trans, nonbinary, and other genderqueer adults.6

If we want the public and policymakers to fully understand California’s housing crisis — and how best to address it — we must look at the role that gender inequities, including domestic violence, play in fueling it. Narratives that frame these politically fraught issues as distinct and intractable can distort how the public and policymakers perceive them. To be sure, communicating about the intersections of such complex topics is challenging. Still, we know it can be done.

In the summer of 2021, for instance, the staff at LAist published a series called “Pushed Out: How Domestic Violence Became The No. 1 Cause of Women's Homelessness in L.A.,” thanks to a grant from the Blue Shield of California Foundation. The series elevated the lived experiences of Southern California women surviving abuse and homelessness, examined how social safety net failures had contributed to their situations, and shared prevention strategies from advocates.

A year later, the Gender Equity Policy Institute (GEPI) drove additional coverage of these issues when it released a report called “Gender and Housing in California: An Analysis of the Gender Impacts of California’s Housing Affordability Crisis.”7 Following the report’s publication, the Los Angeles Times ran an article trumpeting the report’s findings “that women, particularly women of color and single mothers, are more likely to spend more than a third of their income on housing.”8

The article was rich with statistics and quotes from leaders like Betsy Butler, executive director of the California Women's Law Center, who told the Times: "What can you afford if you're not getting paid what you're worth? You certainly can't afford to live in Los Angeles, let alone raise a family in a healthy manner." The article went on to discuss domestic violence specifically, noting that it “can lead to an array of financial and housing insecurity.”

The Los Angeles Times wasn’t the only outlet to cover the report. ABC 7 aired a segment about it,9 and the Sacramento Business Journal ran an article with a special focus on increased rent burdens among women of color.10

The trouble is that these examples are outliers. When our research team examined California-based news about housing and domestic violence, we found that only a fraction of articles discussed the connection between the issues. For every article that made that link, dozens of others did not.

To better understand how domestic violence and California’s housing crisis appear in news coverage, we examined not only the volume of coverage but also how these issues are framed, whose voices are represented, whether solutions are present, and more. We also drew insights from our findings to provide recommendations to advocates who are looking to elevate the connection between domestic abuse and housing insecurity.

Although gender-based violence and housing are both complex social issues that require nuanced approaches, breaking down silos and exposing how they intersect is an important first step toward ensuring that every Californian, no matter their gender, race, or identity, is safe and housed.

Why this project? And why now?

In 2021, Berkeley Media Studies Group (BMSG) worked with the Housing Opportunities Mean Everything (HOME) Cohort, funded by Women’s Foundation California, to identify and explore opportunities for narrative change. The HOME Cohort includes six DV agencies throughout California working to improve the safety and economic security of women in the state who are experiencing homelessness because of DV.

The HOME Cohort is committed to changing narratives about homelessness and DV — a formidable, but not insurmountable, challenge. To help them meet it, BMSG implemented a multipronged research project to assess existing messages and communication resources and synthesize the findings into a communication plan and set of tools to help the Cohort organize its communication and narrative work.

During conversations with the HOME Cohort and other DV providers, we heard considerable interest in these findings, frustration with existing news narratives, and questions about the content of the coverage and how to shift it. To address this feedback, BMSG conducted an ethnographic content analysis of English-language California news about the intersection of homelessness and DV. This report will explore the findings of that news analysis.

Why study the news?

News coverage is important because it sets the agenda for public debate and discussion. Journalists' decisions about whether to cover an issue can raise its profile or relegate it to the background, as issues not covered by the news media remain largely outside public discourse and policy debate.11–13 News coverage also affects how we think about, perceive, and discuss the issues of the day, including, for example, whose perspectives we view as credible and valuable, which solutions are elevated or ignored, and how arguments are characterized.14,15

When it comes to communicating about homelessness and DV, people have many different starting points for their understanding of these topics, why they matter, and what should be done to keep people safe. The way journalists communicate about these issues, then — from the words they use to the way they structure stories — can challenge or reinforce the views that people already hold about DV and homelessness. News can fuel stigma or foster new ways of understanding. It can instill hope or engender doom. News coverage can also provide an entry point and source of information for people who may not otherwise know much about these issues.

Before conducting our own news analysis, we examined existing messages and media studies about homelessness and domestic violence, but we were unable to find research exploring how both domestic violence and homelessness appear in news coverage, as most studies looked at these issues separately.

Understanding news frames: Portraits and landscapes

We know from 30+ years of analyzing news coverage of public health and social justice issues that two types of framing typically appear in the news, sometimes alone and sometimes together:

Portrait or episodic framing centers an individual person or an isolated event. In a story framed as a portrait, audiences learn a great deal about a specific situation or person, which can help to humanize an issue but can also make it challenging to garner support for systemic solutions that go beyond individual behavior change.

Landscape or thematic framing, on the other hand, centers social or institutional responsibility and describes problems or incidents within the context of the environment, systems, and structures. This helps the audience to understand root causes, see social patterns, and view issues as preventable. Such context opens the door to talk about systems and policy changes.

When we looked at existing research into news coverage of domestic violence, studies found that news about domestic violence tends to be episodic and elevate extremes: These “portrait” stories were in the news because of more lethal or fatal incidents, more so than other forms of domestic violence like financial or emotional abuse.16 Coverage rarely discussed the broader context and systems in which domestic violence occurs.17

Additionally, some researchers found that stories about domestic violence often included problematic language featuring so-called “ideal” victims — those characterized as worthy of support.17,18 The “ideal victim” has long been a feature of reporting on various types of violence, in which reporters focus on people who are young, cisgendered, middle class, and white, and depict them as vulnerable, innocent, and blameless. On the other hand, victims of color and those with a history of drugs, sex work, or homelessness are more likely to be portrayed as blameworthy and undeserving of support — or their stories are simply absent.

With this context in mind, our researchers explored questions like:

- Does coverage that explicitly connects domestic violence and homelessness (as opposed to focusing solely on DV) engage in victim-blaming?

- Are stories framed narrowly around individual people and incidents (as portraits), or is the broader social backdrop for domestic violence and homelessness in view (in landscapes)?

What we did: Our methods

To explore connections between DV and homelessness in the news, BMSG set out to identify patterns — and opportunities — in news coverage of DV and homelessness. Specifically, we conducted an ethnographic content analysis19 of news articles from California-based print and online news sources.

Collecting articles about domestic violence and homelessness

Domestic violence and housing instability are both complex issues that happen across a spectrum: domestic violence, for example, can include a range of behaviors including emotional, physical, and sexual abuse.20 Similarly, people who are unhoused may be living on the streets, precariously housed in other ways (i.e. living in shelters, in cars, couch hopping with friends or relatives, etc.), or at risk for becoming unhoused in the near future.21 When DV and homelessness intersect, there is another spectrum of experiences to consider, such as financial abuse.1 To capture stories about the full range of both issues, and how they intersect, we used expansive definitions including many terms and variations.

We used the LexisNexis database to search California newspapers for three sets of print and online news articles, all published between January 1, 2022 and December 31, 2022:

- Articles that included any reference to homelessness or housing instability (search string A);

- Articles that included any reference to domestic violence (search string B);

- Articles that included any of the terms related to homelessness AND any terms related to domestic violence (search string C).

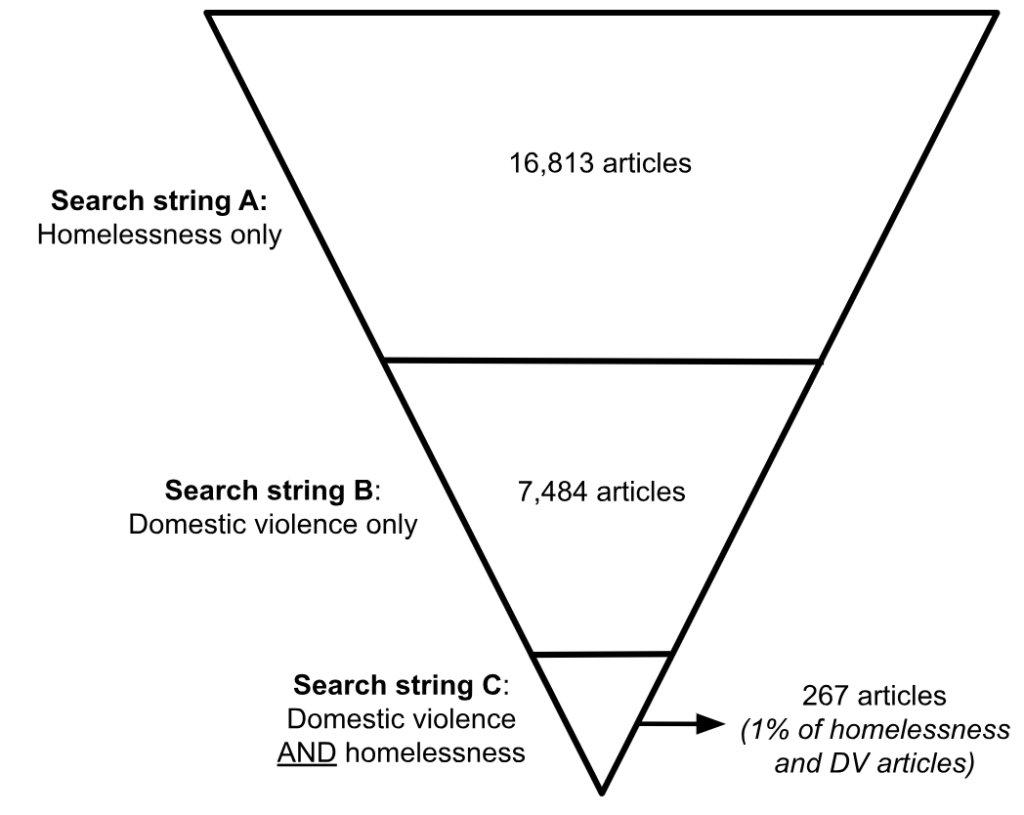

The in-depth analysis that follows is focused on articles from search string C, with search strings A and B providing points of comparison (see Figure 1).

Analyzing articles about domestic violence and homelessness

To capture elements of news stories about homelessness and domestic violence, we combined elements of previous coding instruments, or “codebooks,” that focused specifically on each issue area. The final codebook explored questions like:

- How, if at all, are DV and homelessness connected in news coverage?

- Who speaks in the coverage? Whose perspectives are left out?

- How does the news frame problems related to the intersection of DV and homelessness?

- How, if at all, does the news frame solutions that could prevent DV and subsequent housing insecurity for Californians?

- Does the coverage include language that blames or stigmatizes survivors (for example, involvement with drugs, sex work, or criminal background), or minimizes the harm they experience?

After testing and refining the combined instrument using a subsample of articles, we established coding consensus through extensive conversations to ensure that coder agreement did not occur by chance.

Spanish language results were very limited and beyond our scope of study

Our search only retrieved 14 Spanish-language articles published in print or online California outlets during 2022. Because of the small sample size, we pursued coding of English-language coverage exclusively. This limitation (which is likely related to the small number of Spanish-language print outlets operating in California and accessible through LexisNexis) suggests an opportunity for additional study: For example, future research could explore how outlets like Spanish-language TV and radio cover these issues.

What we found: What the numbers tell us

Finding: Very few articles highlighted the connection between DV and homelessness.

Domestic violence and homelessness are both issues that draw media attention, but how often does the news cover the intersection of these critical problems? We found that articles referencing homelessness (16,813 articles) appeared twice as often as articles referencing domestic violence (7,484 articles). When we looked at articles that mentioned both issues, the numbers dropped still further to just 267 articles published over the course of a year (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Volume of stories published in CA news about domestic violence, homelessness, and domestic violence and homelessness, 2022

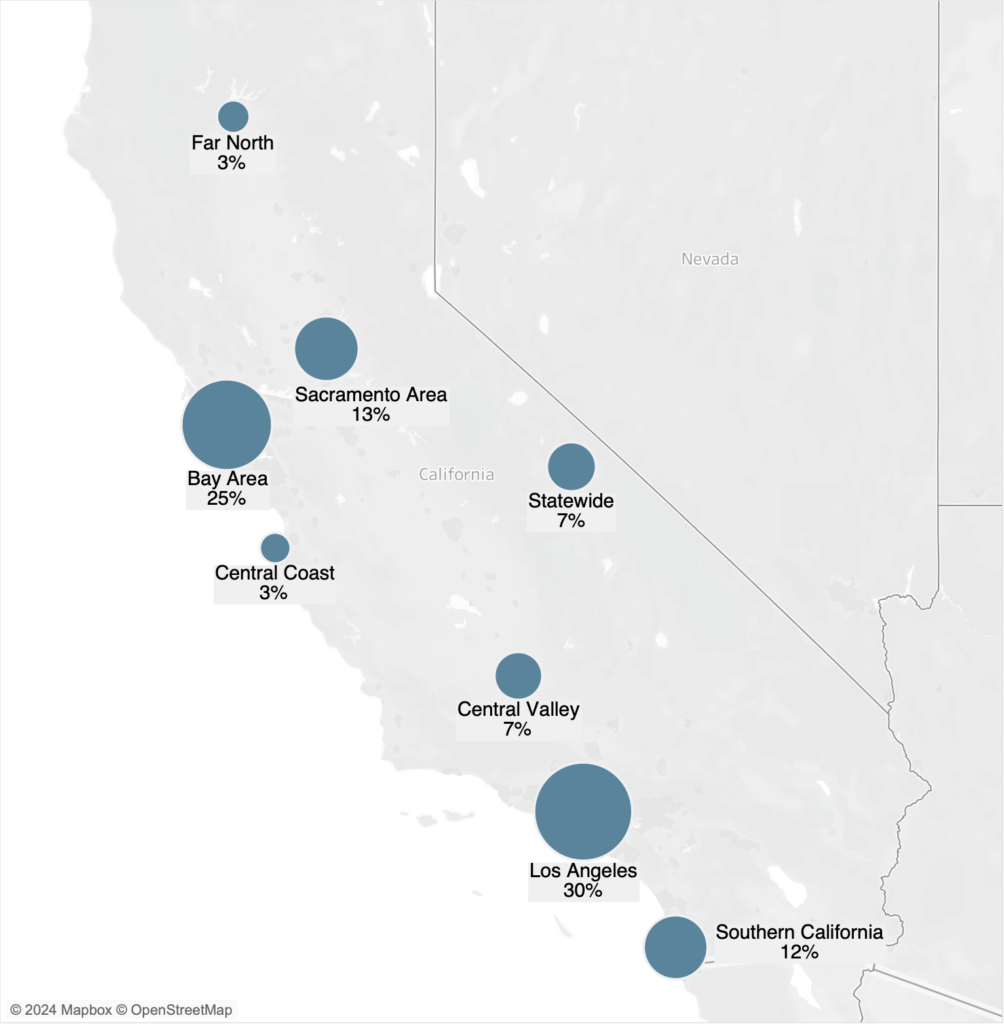

Finding: Outlets serving urban areas were more likely to cover domestic violence and homelessness than were rural outlets.

When stories about domestic violence and homelessness did appear, they were most often published in the Los Angeles Times, Sacramento Bee, and the San Francisco Chronicle. These outlets are based in major population centers in California.

Figure 2: Publication site of stories mentioning domestic violence and homelessness, published in CA in 2022 (n=267)

What we found: Insights from story content and framing

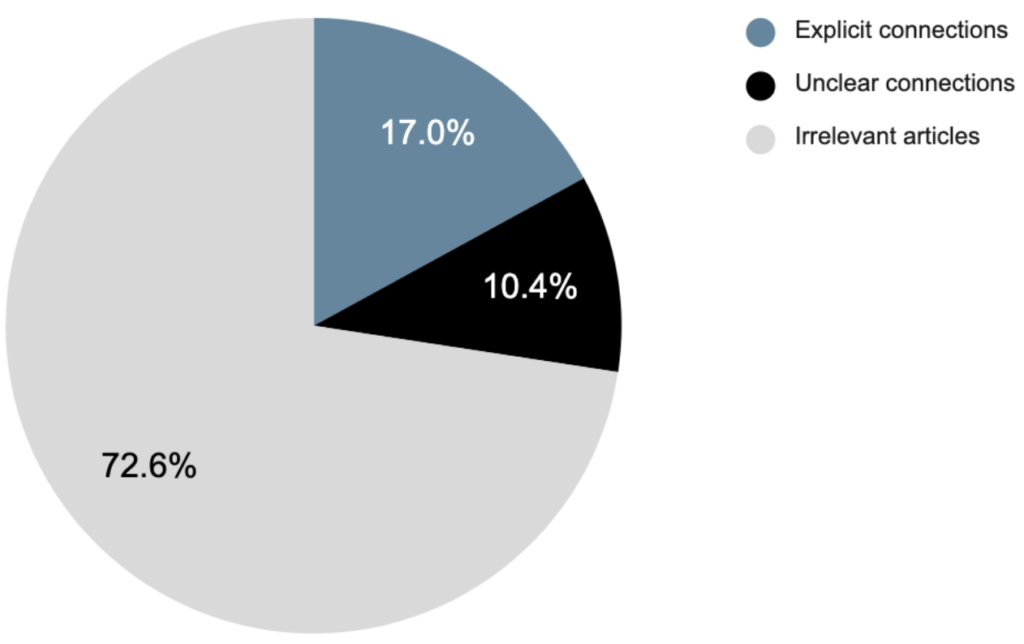

Finding: Even when stories mentioned both domestic violence and homelessness, few substantively addressed the connection between the two issues.

The volume of coverage about domestic violence and homelessness was so small that BMSG coders were able to code all articles about housing insecurity and domestic violence without needing to draw a subsample for analysis. We focused our analysis on articles that substantively discussed the intersection of domestic violence and homelessness, a total of just 74 stories (28% of the sample).*

In articles that substantively discussed both issues, more than half (61%) included causal statements connecting domestic violence and homelessness (see Figure 3 below). A typical article noted, “women are more likely to experience domestic violence, which can lead to an array of financial and housing insecurity.”8 In the remaining relevant articles (38%), both domestic violence and homelessness were discussed, but the connections between the two issues were not apparent. One article about a Bakersfield shelter for unhoused people discussed plans for "the center's continuum of services [to be] streamlined and improved with the merger of the homeless and domestic violence centers into one entity."22

*We systematically excluded stories that made only a passing mention of the issues, which made up the bulk of articles. These included crime reports in which someone happened to be described as homeless (e.g. a crime notice in which a DV survivor was referred to as homeless) or community bulletins that listed local organizations whose clients include domestic violence survivors and people experiencing homelessness.

Figure 3: Volume of stories that substantively discussed domestic violence and homelessness in California news (n=74)

Finding: Milestones in the policy process drove coverage of domestic violence and homelessness.

We wanted to know: When domestic violence and homelessness appear together in the news, why? Why that story, and why that day? Reporters commonly refer to the catalyst for a story as a “news hook.” Many factors can influence why reporters and editors select some stories and not others, from the details of a specific incident to what else competes for attention during the news cycle. We identified the news hook for each article by answering the question, “Why was this article published today?”

The news hook for 54% of relevant stories was a milestone or breakthrough in the policy process. A typical story, for example, documented the Housing Authority of Los Angeles issuing 100% of its emergency housing voucher allocation.23 Additionally, nearly one-quarter of stories (22%) were in the news to announce the onset of a new program or a leadership transition within a program. Stories with anniversary, holiday, or seasonal news hooks accounted for 15% of the coverage including, for example, news stories about Domestic Violence Awareness Month or Child Abuse Prevention Month.

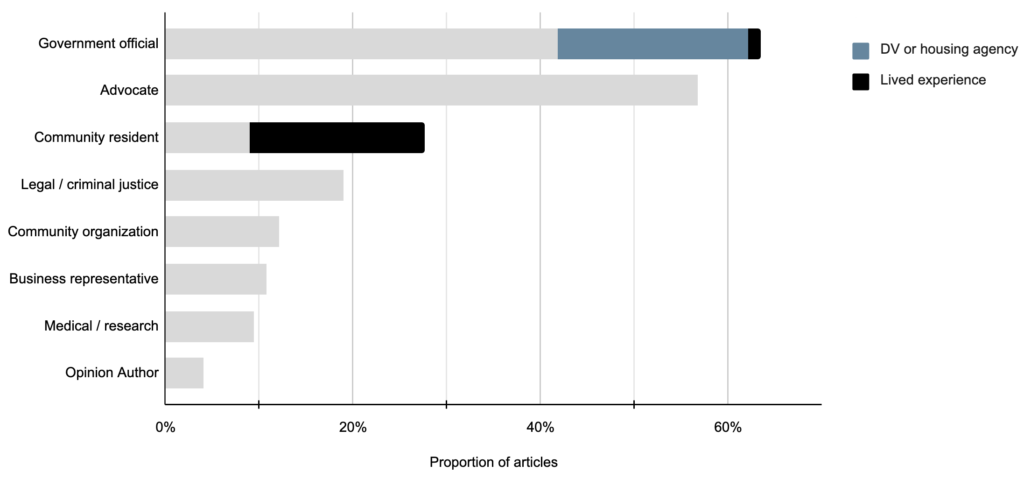

Finding: Government officials, domestic violence prevention advocates, and community members with lived experience most often spoke in the news about domestic violence and homelessness.

To understand whose perspectives are elevated in the news (and whose are obscured), we looked at which speakers were quoted in the news about domestic violence and homelessness. Government officials were most often quoted, appearing in nearly two-thirds (62%) of articles (see Figure 4), though only 20% of articles quoted an official whose role explicitly connected with domestic violence or homelessness (such as representatives from state- or county-level housing and homeless services agencies). More often, the government officials quoted in the news were elected officials whose role was not connected with either issue (42% of articles), like mayors or state senators.

Figure 4: Speakers in California news stories that substantively discussed domestic violence and homelessness published in 2022 (n=74)

Domestic violence and homelessness prevention advocates and services providers appeared in 57% of articles to illustrate the landscape around both issues by telling stories, sharing data, or discussing solutions to domestic violence and housing issues. In a speech marking the start of construction of new permanent housing, Downtown Women’s Center CEO Amy Turk stated, "COVID-19 has especially compounded the risk factors that disproportionately impact women, such as intimate partner violence and eviction.” She concluded, “We must elect a mayor willing to face this issue head on."24

Advocates also authored five of the 14 opinion pieces — op-eds or letters to the editor — that appeared in the coverage. They used the space to name root causes and systemic issues and to urge leaders to pass legislation to protect DV survivors or make housing more accessible. For example, Jessica Merrill of the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence observed that “every single community has a domestic violence organization, but many lack the resources they need to be successful.” Merrill continued: “To honor the memory of Mary Wheat and all victims of domestic violence, more Californians — including legislators — need to get involved.”

More than a quarter (28%) of articles uplifted the voices of community residents, including many who identified themselves (or were identified by journalists) as having lived experience with domestic violence, with homelessness, or with both issues. For example, one DV survivor and mother in San Francisco gave details about her personal experience, describing the shelter where she was staying as giving “peace of mind. … When I walk in, I'm OK. If this wasn't here, I don't know what would happen.”25 Two people in other speaker categories were also identified as having a personal experience with DV and/or homelessness, including one government representative and one lawyer.

Finding: Most articles about domestic violence and homelessness talked about solutions — and responsibility for enacting them — as well as problems.

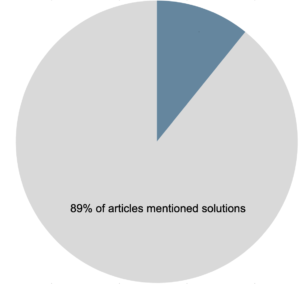

Decades of research illustrate that news about a range of issues tends to focus on problems, rather than on what needs to happen to solve those problems.26–29 It’s unsurprising, then, that 93% of articles named problems to be solved, most of them related to housing insecurity. A typical article noted that despite receiving a record number of federal housing vouchers in 2021, voucher holders in Orange County “have been challenged trying to find available homes in the county's competitive market, and the expiration date for the vouchers is nearing.”30

Coverage of domestic violence and homelessness was different, however, in that solutions also were named in 89% of articles (Figure 5). Most of the solutions named also focused on rectifying housing insecurity issues. One story described efforts of the San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, in partnership with the San Francisco Interfaith Council and Episcopal Community Services, to reinstate “the Winter Shelter Program, which strives to shield homeless people from bitter cold during the night.”31

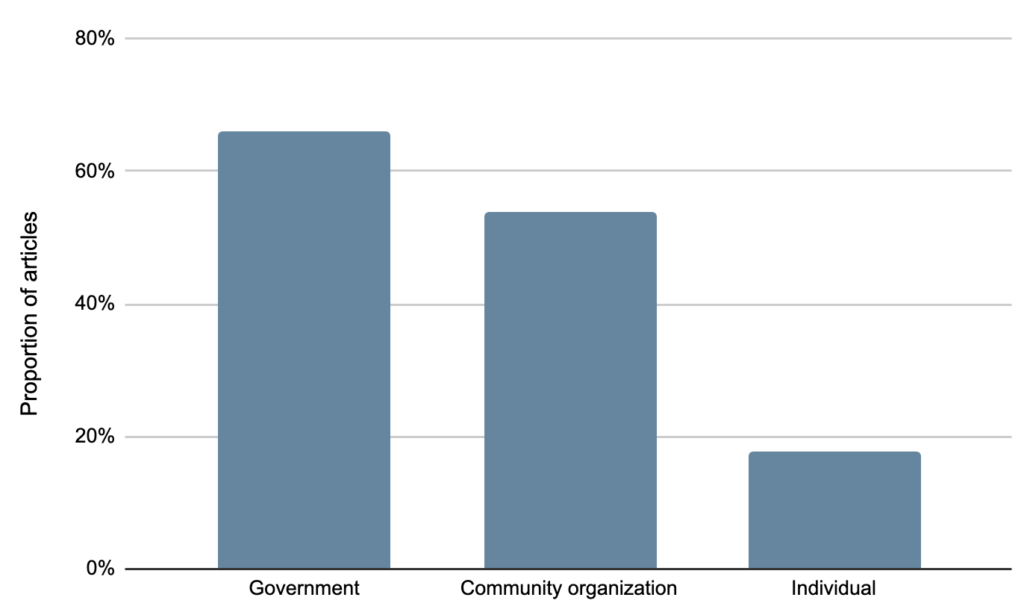

Moreover, nearly every article that named solutions also named the individual, entity, or group who should be held responsible for enacting that solution (88% of all articles, Figure 6). Government officials or entities were named responsible for solutions in two-thirds of all articles. Identifying accountable parties is critical because if journalists don’t, audiences may walk away thinking issues like DV and homelessness are inevitable rather than preventable. Overall, reporters did a commendable job of underscoring the human agency behind these complex social problems. An article about a report from the Little Hoover Commission, for example, called on California leaders to "develop a comprehensive long-term intimate partner violence prevention and early intervention action plan … [because] California must integrate its anti-violence initiative into every segment of society."32

Community organizations, such as shelters and DV resource centers, were also called on to enact solutions in more than half (54%) of all articles. On some occasions, the news spotlighted partnerships between community organizations and local government, as in an article about "a 40-bed site run by Wesley Health Centers and created through a joint effort of the city and county of Los Angeles."33

Figure 6: Proportion of articles that named responsibility for enacting solutions in California news stories that substantively discussed domestic violence and homelessness published in 2022 (n=74)

Finding: The coverage rarely included language or framing that stigmatized or blamed survivors, but other equity-related challenges remain.

In contrast to prior research on news about domestic violence, our analysis of stories about the intersection of domestic violence and homelessness found that only four out of 74 relevant articles used language that directly or indirectly placed blame on survivors of domestic violence. In one of the few articles that included victim-blaming language, the language was included only to provide context for the launch of a domestic violence awareness campaign.

The near absence of stigmatizing language is a win for equity; however, other challenges remain, particularly related to racial equity issues, which few articles mentioned. Domestic violence and homelessness are both unquestionably issues deeply rooted in systemic racism and structural inequities: Black, Latine and Indigenous communities are disproportionately affected by homelessness,34 and Black, Latine, Indigenous,35 and Asian communities36 experience high rates of domestic violence. However, just one in 10 stories about the intersection of these two issues made any reference to structural racism or racial inequities that connect with domestic violence and homelessness. When articles that named inequities appeared, they tended to describe data about the disproportionate rates of rent burden and homelessness experienced by Black, Latine, and immigrant communities. Only two articles cited data on the rates of domestic violence on women of color.

Additionally, though solutions were prevalent in the coverage, few articles named approaches explicitly focused on addressing racial inequities. A rare example noted that “Long Beach spent more than $3 million to support communities hurt by inequities, including five more staff positions to promote health equity, increased staff for the Office of Equity, and begun to redesign the Police Department approach to community safety.”37

Summary and next steps

Domestic violence is underreported, and news coverage that connects DV and homelessness is especially rare. Our initial news sweep found that more than twice as many articles mentioned homelessness as mentioned domestic violence — and only 1% of articles mentioned both issues together. Even fewer articles substantively discussed both issues and how they are connected, further limiting news readers’ exposure to in-depth discussion of these complex intersecting issues, why they matter, and what to do about them.

Fortunately, what coverage we did find includes many strengths: For example, while rare, stories connecting domestic violence and homelessness tend to regularly feature the voices of community residents, including those who have experienced homelessness and/or DV firsthand. In addition, advocates have successfully driven or appeared in much of the coverage that there is, and calls for solutions — and shared responsibility for those solutions — were visible in many articles (although most solutions named focused exclusively on dealing with housing problems, instead of problems unique to unhoused survivors of DV).

Our findings raise important questions about how advocates can work with journalists to increase the amount of coverage about DV and homelessness while maintaining or improving the level of quality:

- What opportunities can advocates leverage to create more news?

- What would it take to help journalists — and their audiences — more fully understand the connection between housing insecurity and abuse?

Recommendations for advocates to effect narrative change

Our findings show that advocates are already doing excellent work using the media to communicate strategically about homelessness and domestic violence. However, there are opportunities to expand and amplify existing work. Of course, journalists play a large role in determining the volume and quality of content that is available to the public, but there are several ways that advocates can help journalists improve coverage.

On the following pages are a few recommendations to help advocates make the most of efforts to engage with the media:

Build relationships with reporters and editors.

Whether you are pitching a story idea, submitting an opinion piece, or providing information as an expert source, you will have a better chance of gaining traction if you have already built trust and rapport with the journalist you are approaching. One place to start is simply by identifying reporters who are already grappling with these issues and showing appreciation for any coverage that you thought was well done. If their coverage seems limited (perhaps the reporting focused exclusively on one issue or the other but did not show how they are connected), reach out with curiosity. Ask if they are aware of the connection and, if not, offer to share materials and/or schedule a call to discuss how the link between homelessness and DV is manifesting in your community.

Most reporters take very seriously their commitment to serving readers, but they can only do that if they are aware of an issue in the first place. To that end, you can also offer to put reporters in touch with expert sources who work at the intersection of DV and housing insecurity and can further explain how they overlap. Reporters and editors are always looking for fresh, new story angles, so you may be surprised by how welcome your ideas and assistance are.

Identify and train credible messengers, especially those who have been impacted personally.

Journalists often operate under tight deadlines, so when they are looking for sources to interview, it may be difficult to find community residents who are willing and able to speak about their experiences with issues as stigmatized as homelessness and DV. Domestic violence in particular is already severely underrepresented in news coverage, and issues like privacy and safety can make it especially challenging to go beyond traditional sources — those typically associated with law enforcement or social services — and incorporate the voices of survivors.

Advocates can become important allies and resources for journalists by helping to cultivate such sources so that readers can relate to the people behind the statistics. Doing so will help to expand both journalists’ and audiences’ views on who is considered an expert. When training these messengers, be sure to keep not only your communication goals at the forefront but also the survivors’ comfort and safety. Talking with journalists requires enormous vulnerability and can be overwhelming, so budget extra time for breaks and check in with them throughout the coaching process to ensure that they feel supported and empowered, rather than part of a transaction. When they are ready to proceed, help them position their stories in ways that connect to broader systemic challenges with housing and DV. And when introducing them to journalists, remind reporters that these sources have deep knowledge not only of the problem but also of potential solutions. It is important to show that people who have experienced or are experiencing DV and/or homelessness have agency and identities beyond being victims.

Help journalists reimagine what is possible.

Our researchers found that news often covered services or policies designed to react to the problems of DV and homelessness; however, news coverage rarely addressed how to improve systems to prevent these issues in the first place. Once you’ve established a relationship with a reporter, you can help them to go beyond reporting only on how current policies and systems are broken to envision what systems might look like if they were functioning more smoothly and better serving the community. For example: Housing policies can be crafted to better support survivors (e.g., by making it easier for survivors to modify rental properties to increase safety so they can stay in their homes); social safety net programs can be strengthened to provide cash benefits or more robust food assistance; and paid leave or “sick and safe leave” policies can allow DV survivors the time away from work needed to seek medical attention, counseling, or other social services.

Identify easy wins — opportunities within existing workflows to illuminate the link between DV and homelessness.

Thousands of stories are published each year on domestic violence and homelessness separately — especially the latter, according to our findings. Although it might seem like a Herculean task to forge more connections between the issues and create a new narrative that elevates these intersections, remember that narrative change work is incremental. Not every story has to do everything. Not all work has to be transformative to be worthwhile. For example, if you are pitching a story or writing an opinion piece primarily about homelessness and housing policy, make sure it mentions DV, even if that is not the main focus. Similarly, if you are pitching a story or an op-ed about domestic violence, make sure it mentions homelessness. Even when a story is not centered around this connection, make sure it is present. Collectively, the impact of these efforts could be significant, especially when repeated over time, across multiple regions and outlets.

Piggyback off current coverage to further expand the narrative.

Most of the recommendations above describe proactive strategies for shaping news coverage. But reactive strategies are beneficial, too. By “reactive,” we are referring to steps you can take after an article has been published, even if you were not involved in its development or editing.

For example, if a story comes out that exclusively discusses DV or homelessness, consider piggybacking off of it by writing a blog, posting to social media, or submitting a letter to the editor (see our template here). You can use the original article as your hook and then broaden the frame to show readers what’s missing or applaud an example of solid coverage, as Debbie Chang, president and CEO of the Blue Shield of California Foundation, did in this letter to the editor published in the San Francisco Chronicle. In her letter, Chang celebrated recent coverage that named the link between domestic violence and homelessness and highlighted the important work being done by organizations like the San Francisco Women’s Housing Coalition. Chang also emphasized the importance of listening to survivors, who often have valuable insight into effective prevention strategies.

Letters to the editor like Chang’s remain a highly read form of content, even in today’s saturated media environment. And self-published content like blogs, podcasts, or social media posts carry the benefit of immediacy: There is no need to go through a third party for approval before sharing your content, and you can interact directly with your audience.

Conclusion

Everyone deserves a safe, stable place to call home, but for far too many Californians, that basic necessity is out of reach. The state’s housing crisis persists despite robust advocacy efforts, in part because the issue is deeply intertwined with many others, including domestic violence, and those interconnections are hidden. Although DV is prevalent in California and beyond, it is woefully underreported in the news, and its role in fueling homelessness is all but absent. Expanding narratives about homelessness to include its connection to domestic violence, and vice versa, is one immediate and achievable step that advocates can take to strengthen the case for change. As we often say at BMSG, you can’t solve a problem you don’t know about, and unearthing the links between these issues is long overdue. Telling more stories that elevate the intersection of DV and homelessness can bolster and shape existing advocacy efforts to create the kind of California that we know is possible.

Acknowledgments

This report was authored by Berkeley Media Studies Group’s media researchers Kim Garcia, MPH, and Sarah Perez-Sanz, MPH; Director of Research and Associate Program Director Pamela Mejia, MPH, MS; and Strategic Communication Director, Heather Gehlert, MJ.

Many thanks to Hina Mahmood for coding assistance; to Krista Colon and Jennifer Willover of the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence for their insights, guidance, and unflagging support; and to the members of the Housing Opportunities Mean Everything (HOME) Cohort for their content expertise and thoughtful questions.

This research report was made possible through the support of the Blue Shield of California Foundation.

References

1. Altheide, D. L. (1987). Reflections: Ethnographic content analysis. Qualitative Sociology, 10(1), 65– 77. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00988269

2. Office of Family Violence Prevention and Services, an office of the Administration for Children and Families within the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2016). Domestic Violence and Homelessness Statistics, Fact Sheet. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofvps/fact-sheet/domestic-violence-and-homelessness-statistics-2016

3. Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence. (n.d.). STATISTICS ON VIOLENCE AGAINST API WOMEN. https://www.api-gbv.org/about-gbv/statistics-violence-against-api-women/

4. Batko, S. (2023). Los Angeles County Women’s Needs Assessment: Findings from the 2022 Survey of Women Experiencing Homelessness. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023- 07/Los%20Angeles%20County%20Women%E2%80%99s%20Needs%20Assessment.pdf

5. Brazil, B. (2022, April 14). O.C. housing agencies struggle with ‘unprecedented’ number of housing vouchers about to expire. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-04-14/o-c-housing-agencies-face-unprecedented-number-of-housing-vouchers-before-they-expire

6. Carlyle, K. E., Slater, M. D., & Chakroff, J. L. (2008). Newspaper coverage of intimate partner violence: Skewing representations of risk. Journal of Communication, 58(1), 168–186.

7. Dearing, J. W., & Rogers, E. M. (1996). Agenda-setting. Sage.

8. Dorfman, L., Wallack, L., & Woodruff, K. (2005). More than a message: Framing public health advocacy to change corporate practices. Health Education & Behavior, 32(4), 320–336.

9. End Domestic and Gender-Based Violence (ENDGBV). (2021). 2020 Report on the Intersection of Doemstic Violence, Race/Ethnicity, and Sex. New York City Mayor’s Office to End Domestic and Gender-Based Violence (ENDGBV). https://www.nyc.gov/assets/ocdv/downloads/pdf/endgbvintersection-report.pdf

10. Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

11. Gamson, W. (1992). Talking politics. Cambridge University Press.

12. Gender Equity Policy Institute. (2022). Gender & housing in California: An analysis of the gender impacts of California’s housing affordability crisis. Gender Equity Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6941631

13. Gilchrist, K. (2010). “Newsworthy” Victims?: Exploring differences in Canadian local press coverage of missing/murdered Aboriginal and White women. Feminist Media Studies, 10(4), 373– 390. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2010.514110

14. Gonzales, K. (2023, August 16). Women of color are feeling the unbalanced burden of Sacramento’s rent crisis. Sacramento Business Journal. https://www.bizjournals.com/sacramento/news/2023/08/16/women-of-color-rent-crisis-burden.html

15. Griffith, C. (2023, October 13). Millions of People Endure Homelessness Every Year. https://invisiblepeople.tv/millions-of-people-endure-homelessness-every-year/

16. Haire, C. (2022, July 1). Long Beach homeless population spikes 62% compared to 2020, survey reveals; officials blame pandemic. Long Beach Press-Telegram. https://www.presstelegram.com/2022/07/01/long-beach-homeless-population-spikes-62-compared-to-2020-survey-reveals-officials-blame-pandemic/

17. Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles. (2022, July 7). HACLA Issues 100% of Emergency Housing Voucher Allocation. Los Angeles Sentinel. https://lasentinel.net/tag/housing-authority-of-the-city-of-los-angeles

18. Iyengar, S. (1991). Is anyone to blame? How television frames political issues. The University of Chicago Press.

19. Kitzinger, J., & Skidmore, P. (1995). Playing safe: Media coverage of child sexual abuse prevention strategies. Child Abuse Review, 4, 47–56.

20. Levin, R., McKean, L., & Raphael, J. (2004). Pathways to and from Homelessness: Women And Children In Chicago Shelters. Center for Impact Research. https://search.issuelab.org/resource/pathways-to-and-from-homelessness-women-and-children-inchicago-shelters.html

21. Mays, M. (2022, August 19). California Politics: Why the housing crisis is a women’s issue. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/newsletter/2022-08-19/california-politics-housing-crisis-womens-issue-ca-politics

22. McCombs & Reynolds. (2009). Media effects: Advances in theory and research (J. Bryant, Ed.; Third edition). Routledge.

23. McManus, J., & Dorfman, L. (2014). Distracted by drama: How California newspapers portray

intimate partner violence. Berkeley Media Studies Group.

http://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/issue-13-distracted-by-drama-how-california-newspapers-portray-intimate-partner-violence

24. Moench, M. (2022, November 5). S.F. homeless families found an oasis. But this city shelter

could shutter if negotiations fail. San Francisco Chronicle.

https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/sf-homeless-oasis-hotel-17560389.php

25. Morrison, A. M. (2006). Changing the Domestic Violence (Dis)Course: Moving from White Victim to

Multi-Cultural Survivor. Wayne State University. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/lawfrp/423/

26. Munoz, A. (2022, August 24). Housing crisis hits women harder in California, group’s research finds. ABC7 News. https://abc7.com/affording-housing-womens-issues-cost-of-living-california-gender- equity/12159267/

27. National Alliance to End Homelessness. (2020, June 1). Racial Inequalities in Homelessness, by the Numbers. https://endhomelessness.org/resource/racial-inequalities-homelessness-numbers/

28. National Domestic Violence Hotline. (n.d.). What Is Domestic Violence? Retrieved April 3, 2024, from https://ncadv.org/learn-more

29. Reyes, E. A. (2022, April 21). A new skid row facility where homeless women can try ‘to get whole and heal.’ Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-04-21/oasis-skid-row-recuperative-care-homeless-women

30. Safe Housing Partnerships. (n.d.). The Intersection of Domestic Violence and Homelessness. Retrieved April 3, 2024, from https://safehousingpartnerships.org/sites/default/files/2017-05/SHP-Homelessness%20and%20DV%20Inforgraphic_1.pdf

31. Scheufele, D., & Tewksbury, D. (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 9–20.

32. Smith, P. (2022, February 8). CEO of homeless center discusses clients, outlook with county supervisors. The Bakersfield Californian. https://www.bakersfield.com/news/ceo-of-homelesscenter-discusses-clients-outlook-with-county-supervisors/article_04cf3da2-8925-11ec-ac75-ab1f516226d4.html

33. Tso, P. (2022, January 31). Permanent Supportive Housing Unit Breaks Ground in North Hollywood. LAist. https://laist.com/news/housing-homelessness/permanent-supportive-housing-unit-breaks-ground-in-north-hollywood

34. Umanzor, J. (2022, November 30). As cold front descends on Northern California, cities offer temporary winter shelters. San Francisco Chronicle. https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/As-cold-front-descends-on-Northern-California-17622675.php

35. US Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2013). Impacts of Housing Discrimination Against LGBTQIA+ People. US Department of Housing and Urban Development. https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/fair-housing/lgbtqia-fair-housing-toolkit/fair-housing-in-your-daily-operations-as-a-housing-provider/impacts-of-housing-discrimination-against-lgbtqia-people/

36. Wong, J. S., & Lee, C. (2021). Extra! Extra! The Importance of Victim–Offender Relationship in Homicide Newsworthiness. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(9–10), 4186–4206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518789142

37. Wozniak, J. A., & McCloskey, K. A. (2010). Fact or Fiction? Gender Issues Related to Newspaper Reports of Intimate Partner Homicide. Violence Against Women, 16(8), 934–952. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801210375977